Cities start, grow, expand, and usually—mainly in developing countries—exceed their limits, overflowing into rural and wild lands. This city growth applies not only to the imposition of manmade facets on geographical extensions, but to increases in the city’s complexity and dynamics. Urban phenomena start and keep mistreating nature beyond the city’s official boundaries, not just in physical terms, but through the so-called ecological footprint, a term which describes multiple alterations of the healthy functioning of the land both close and quite distant from the urban settlement.

Because cities grow on territories that previously exhibited their natural qualities and ecosystem functions, we should recognize natural structures, respecting their traits and articulating urban sprawl according to their form; or, at least, we should emphasize traces of the natural ecological systems when irreversible modifications and a new, non-stimulating landscape has emerged.

Why do we seem unable to do this?

Take a glance at Figure 1, starting with a simple, formal approach to a landscape transformation. One may say that the silhouettes of the slopes on both sides keep a certain similarity. Nevertheless, the one on the left has been forced into a new shape by leveling for new construction. Among other changes, water flow has been altered to occur perpendicularly to its natural flow, which will be carried by a tube at the edge, in a direction opposite to that proposed by nature. The shape of the building bursts abruptly in the scene and impedes one’s perception of the small valley, although its texture is similar to the texture of what is built on the slope to the right. The color on the new slope on the left makes a strong and adverse contrast with the one on the right. We can see the same effect when talking about texture. The growth of vegetation that could cover that slope, helping it to maintain a visual relationship to the other side, has been banned, and its diversity is missing.

Our negative reaction to the appearance of this setting is an alert that something is going wrong. The shocking effects of its appearance also convey unconscious discomfort to people. According to several authors (Canter 1987, Rapoport 1982, Granada 2007) this discomfort is part of the motivation for inappropriate behaviors. In other words, a healthy and stimulating landscape will help the development of a healthy society. The designer´s responsibility goes beyond simple formal composition; it is not a matter of taste or individual preferences. The final appearance should reflect the correct articulation of many interlocking systems—both natural and manmade—working in a balanced way, paying attention to natural inertia in order to contribute to a better society.

“Urban nature may be visible, but the processes are not. The vital functions of ecosystems are not readily appreciated until things go seriously wrong”, writes David Goode. Unfortunately, this reality is persistently repeated. Recent and frequent disasters are telling us about the urgent need to read nature carefully, to learn from her, and to apply her teachings, especially in our urban world.

Authorities and planners worry about how much area is occupied, but occupying more area—a necessity as population grows—would matter less if we did so in a less harmful way. The key issue is “how” we do it, and the values that underlie the expansion. If we are motivated by money for the benefit of a few—and the assumption that Earth’s surface is a business resource—before the welfare of many, there will be no future. Welfare cannot rely on consumption!

How to knit relationships between the wide world and the urban one? Or, between this and the small one, that of human scale, that of day-to-day living or the surroundings of our intimate existence? How to manage to write properly on nature in the urban landscape, to offer an inspiring reading to others? How to achieve such a reading if, usually, building activities dominate nature, ignore it, abuse it, and—in the best of cases—hide it?

The concept of city metabolism is well known, and has been clearly explained by Abel Wolman (1965), Herbert Girardet (1996, 2004) and Richard Rogers (2000), to name just a few. Nevertheless, from the point of view of developers, it seems that the responsibility to keep healthy living conditions intact lies solely with environmental authorities . Unfortunately, such public offices work separately from the activities inherent to urban development, and with a focus only on quantifiable issues. Their concern lies with how many square meters of green surface per inhabitant are left, how many trees are planted in a period of time, or what is the distance technically allowed between those trees, instead of on the resultant quality of the space, its coherence with nature functionality, or as a complex fragment of a whole.

How to go from the distant framework of high mountains or immense sea to the very small nature of weeds between the tiles, or from intense traffic noise to the soft sound of a singing bird?

Richard Scott brought a sensible reply to this question in TNOC’s 2016 roundtable about making urban nature more “visible” to people. He wrote, “wildflowers have proven to be a great platform and a connecting force for a new kind of cultural ecology, which brings nature into people’s lives.”

This statement fits with the idea of a constant round-trip from broad to tiny and vice versa—a recommended strategy that supports proper answers in urban interventions, be those big or small.

Taking care of every small area, as part of a whole natural “organism”, would be part of a successful way to reconcile nature’s manifestations at multiple scales in an urbanized world. This requires coherence, connection, and systematization of actions as parts of a whole.

A technical view, connected with a sensible attitude, would be another integral part of it. If we try to imitate nature, please let´s do it properly!

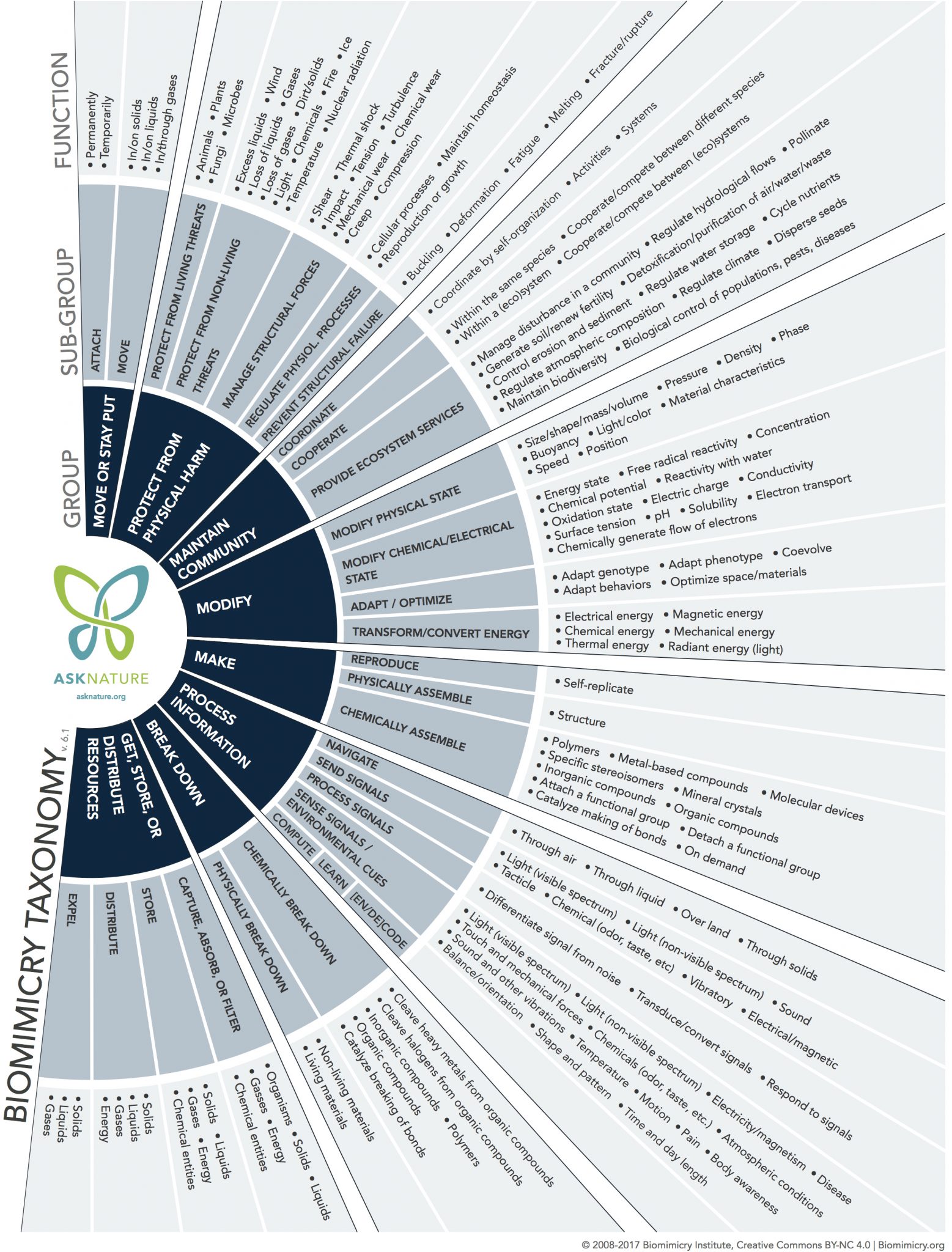

In writing this piece, I received a message from the Biomimicry Institute, where the authors present their Biomimicry taxonomy chart, and there I found a clear starting place for answering my questions.

The Biomimicry Institute says: So although we can’t call nature on the phone, or text her our questions, or read her mind, we can still consult our ecological mentors, and find “time-tested” solutions to our greatest design challenges.

To this list of strategies, I would add observing nature and reading from the “texts” that she has been writing on the surface of the earth throughout time.

The Biomimicry Institute continues, writing, “Ask Nature and make it easier to search. One way to “ask nature” for design guidance is to break your challenges down into their fundamental functions—the specific outcomes your design needs to achieve. See Figure 1.

Here, I found a good lesson that leads from broad actions or intentions that designers may have in mind—and which they express in their inner circles—to a more detailed level of actions, which end up in the outer circle of the public. We must take into account all of the functions involved before any visions or decisions are materialized.

That is to say, carrying out development interventions to satisfy urban functions must go with ecological conditioning. It doesn´t mean to solving broad problems instantly, but it does mean being aware of the implications and connections of small interventions on the performance of the whole.

The fan below illustrates, many ideas and, when all of these are connected, it becomes easier for us to see the panorama, to relate and connect to decision-making processes that direct us towards better urban development.

Some key landscape-oriented recommendations for planners of city expansion would be:

- Conduct a real and integrated survey of natural conditions and ecosystem functioning before assigning land uses.

- Pay special attention to watercourses, even if they are intermittent

- Carry out a landscape character assessment involving the local community

- Always bear in mind the human scale. In the end, humans are those who enjoy or suffer the experiential landscape.

- Anticipate the effects of every proposal or decision at large, medium, and small scales.

- Propose respecting the physiognomy of the place, and following its visual composition elements.

- If you already know geometry, please stop! (As our Colombian writer Germán Arciniegas (1973)), says.

For a better urban landscape, we must recognize our belonging to the natural world and free ourselves from the growing domination of technology and Euclidean geometry.

Together with landscape sensibility, ecological intelligence will help us to achieve better urban habitats to welcome better citizens.

Gloria Aponte

Medellín

About the Writer:

Gloria Aponte

Gloria Aponte is a Colombian landscape architect who has been practicing for more than 30 years in design, planning and teaching. She lead her own firm, Ecotono Ltda., in Bogotá for 20 years. She led the Masters program in Landscape Design at Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, in Medellín. She is a consultant and belongs to "Rastro Urbano" research group at Universidad de Ibagué, and also the Education Clúster at LALI (Latinamerican Landscape Initiative).

Add a Comment

Join our conversation