Today’s post celebrates some of the highlights from TNOC writing in 2019. These contributions—originating around the world—were one or more of widely read, offering novel points of view, and/or somehow disruptive in a useful way. All 1000+ TNOC essays and roundtables are worthwhile reads, of course, but what follows will give you a taste of 2019’s key and diverse content.

Check out highlights from previous years: 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012.

A key event for TNOC in 2019 was The Nature of Cities Summit in Paris. Attended by almost 400 people from 60 countries, TNOC Summit was a major undertaking to model a new collaborative spirit in urbanism. We continue to publish outputs from Summit. You can see them here, along with the Summit report. Planning for the next Summit is underway, and will be announced soon.

The Stories of the Nature of Cities 2099 prize for Flash Fiction attracted 1200 entries from 116 countries. We awarded seven top prizes—women from the U.S., Canada, and India—and in May 2019 we published a book of 57 stories from 21 countries: A Flash of Silver Green. The 2020 version of the prize has just completed accepting submissions—over 1,000 from 99 countries—and we will produce a new book of collected stories early in 2021.

In essays, roundtables, and reviews we continue to seek the frontiers of thought found at the boundaries of urban ecology, community, design, planning, and art. Importantly, we’ve attracted more and more readers: over a million people have visited TNOC. and in 2019 we had readers from 3,500+ cities in 150+ countries.

Thank you. We hope to see you again in 2020.

(Banner photo is by Paris architect Vincent Callibaut.)

Donate to TNOC

TNOC is a public charity, a non-profit [501(c)3] organization in the United States, with sister organizations in Dublin (TNOC Europe) and Paris (TNOC France). We rely on private contributions and grants to support our work, and to demonstrate grassroots support to our organizational funders. No pay-wall exists in front of TNOC content. So, if you can, please help support us. Click here to help.

The Nature of Cities Summit

The Nature of Cities (TNOC) Summit, held in Paris from 4-7 June 2019, brought together a unique diversity of thought- leaders and practitioners to catalyze a cross- disciplinary movement for collaborative green cities. The Summit convened diverse voices and actors, designing interactive sessions to build new connections and propel change—both on an individual and organizational level. Participants ranged from artists, writers, and activists to people working in academia, urban planning, policy, and practice.

A Flash of Silver Green

A Flash of Silver Green

We asked people to imagine future cities, in the form of a flash or short fiction contest. Our original prompt read like this: What are the stories of people and nature in cities in 2099? What will cities be like to live in?

Of 1,200 submissions from 116 countries, 57 from 21 countries were collected in this book, including the seven that we judged to be prize-winners, authored by women from the United States, Canada, and India. You can get a copy of A Flash of Silver Green directly from the publisher.

Roundtables

How is the concept of “stewardship” and “care for local environments” expressed around the world?

This roundtable was inspired by “seed session” workshop “Talk, Map, Act” at the TNOC Summit where we gathered diverse stories of engagement with stewardship from all around the world. To continue this journey we explore the words people use for the constellation of activities suggested by the English word “stewardship”. So, we asked 25 practitioners—scientists, activists, artists, planners, practitioners—from five continents: in your context and experience, what is the word or phrase used for the concept of “actively taking care of things, such as the environment”? The answers are all over the map. In many languages, there is no direct translation to the English word “stewardship”. But there are many phrases that convey the activity of care—activities that in many countries are newly developing and advancing.

This Roundtable was curated by Lindsay Campbell, Erika Svendsen, and Michelle Johnson of the U.S. Forest Service.

With contributions from: Nathalie Blanc, Paris; Lindsay Campbell, New York; Zorina Colasero, Puerto Princesa City; Kirk Deitschman, Waimānalo; Johan Enqvist, Cape Town; Emilio Fantin, Bologna; Artur Jerzy Filip, Warsaw; Carlo Beneitez Gomez, Puerto Princesa City; Cecilia Herzog, Rio de Janeiro; Michelle Johnson, New York; Kevin Lunzalu, Nairobi; Patrick Lydon, Osaka; Romina Magtanong, Puerto Princesa City; Heather McMillen, Honolulu; Ranjini Murali, Bangalore; Harini Nagendra, Bangalore; Jean Ferus Niyomwungeri, Kigali; Jean Palma, Manila; Beatriz Ruizpalacios, Mexico City; Huda Shaka, Dubai; Erika Svendsen, New York; Abdallah Tawfic, Cairo; Diana Wiesner, Bogotá; Fish Yu, Shenzhen

There is a feeling among many that in broad brush, at least, we know what we need to do to make cities better for people and nature. Yet, cities often, even typically, lag in their efforts to be more resilient, sustainable, livable, and just through greening. Why?

There are four threads in the responses: (1) research and data, and perhaps even “knowledge” is, by itself, insufficient; (2) while we mostly have enough research knowledge to act, it doesn’t necessarily apply everywhere, as we lack knowledge applicable to the global south; (3) we all, including scientists, have to become activists for change toward better cities; (4) we need transparency and engagement across sectors of the public realm.

With contributions from: Adrian Benepe, New York; Paul Downton, Melbourne; Ana Faggi, Buenos Aires; Sumetee Gajjar, Cape Town; Russell Galt, Edinburgh; Rob McDonald, Washington; Huda Shaka, Dubai; Vivek Shandas, Portland; Phil Silva, New York; Naomi Tsur, Jerusalem

When I first encountered “urban ecology”, and urbanism generally, what attracted me was the essential collaborativeness of cities and their design—that cities are, or at least should be, collaborative creations. Indeed, this is the fundamental (and ideally fun) and foundational idea of TNOC: let’s put different types of people into the same space and see what emerges. So, we asked a collection of TNOC contributors—scientists, artists, planners, designers, engineers, policy makers—about their own experience with collaboration. It is a rich vein of response, and some threads stand out about the collaborative experience: It challenges us to trust. It is often surprising. It is often difficult. Sometimes there is tension. It takes time. It demands personal growth. It requires acknowledgment of others. It asks us to question our own points of view. It thrives in the in-between spaces. There is no one way. It is an act of transformation.

With contributions from: Pippin Anderson, Cape Town; Carmen Bouyer, Paris; Lindsay Campbell, New York; Gillian Dick, Glasgow; Lonny Grafman, Arcata; Eduardo Guerrero, Bogotá; Britt Gwinner, Washington; Keitaro Ito, Kyushu; Madhusudan Katti, Raleigh; Jessica Kavonic, Cape Town; Yvonne Lynch, San Sebastian; Mary Mattingly, New York; Brian McGrath, New York; Tischa Muñoz-Erikson, Río Piedras; Jean Palma, Manila; Diane Pataki, Salt Lake City; Bruce Roll, Portland; Wilson Ramirez, Bogotá; David Simon, Gothenburg; Tomomi Sudo, Kyushu; Dimitra Xidous, Dublin

National Park City: What if your city were a National Park City, analogous to what London created? What it would be like? What would it take to accomplish?

National Park City: What if your city were a National Park City, analogous to what London created? What it would be like? What would it take to accomplish?

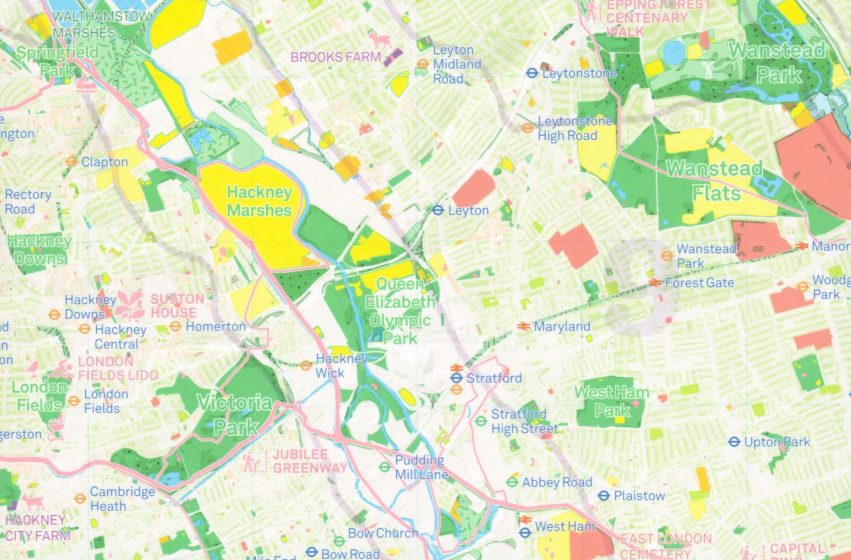

London’s communities have recognized and celebrated the role of the network of green and blue spaces in the life of the city in the form of a grassroots campaign to make London the first National Park City. The six year campaign saw London National Park City launched in 2019. Other cities will follow. Can this idea be applied in other cities? How? We asked a variety of people involved in parks and open space around the world. Some are in cities actively contemplating such a national park city approach. For others, it was a new idea. The London National Park City idea is both a formal recognition of the scope and benefits of the macro-park that is all London’s open spaces, and also a call for London’s population to see and get engaged with their myriad green spaces.

This Roundtable was curated by Daniel Ravel-Ellison and Alison Barnes.

With contributions from: Méliné Baronian, Versailles; Maud Bernard-Verdier, Berlin; Ioana Biris, Amsterdam; Timothy Blatch, Cape Town; Aletta Bonn, Berlin; Geoff Canham, Tauranga; Samarth Das, Mumbai; Gillian Dick, Glasgow; Luis Antonio Romahn Diez, Merida; Ana Faggi, Buenos Aires; Eduardo Guerrero, Bogotá; Sue Hilder, Glasgow; Mike Houck, Portland; Sophie Lokatis, Berlin; Scott Martin, Louisville; Sebastian Miguel, Buenos Aires; Gareth Moore-Jones, Ohope Beach; Rob Pirani, New York; Julie Procter, Stirling; Tom Rozendal, Breda; Snorri Sigurdsson, Reykjavík; Lynn Wilson, Victoria

Essays

Smart vs Green: Technology Paradigms Battle it Out for the Future City

Sarah Hinners, Salt Lake City

Vision A—The Smart City: The city is an intricate network of digital communications, computations, and connections. Vision B—The Ecological City: The city is an intricate network of living systems interacting with one another, with built structures, and flows of water, materials, organisms, and information. These alternative visions are not necessarily mutually exclusive, of course, but in my experience they are rarely combined in the same conversation or planning process.

Mosaic Management: The Missing Ingredient for Biodiversity Innovation in Urban Greenspace Design

Stuart Connop and Caroline Nash, London

As we homogenise and sterilise our rural landscapes with intensive agriculture, and disconnect our populations from nature in shining metropolises, it is more pressing than ever to maximize the potential for urban areas to support wildlife. Innovative urban greenspace design also needs innovative management if our nature-based solutions are to sustain diverse populations of biodiversity in urban areas.

Proposals for the Environment and the Future of Cities

Kevin Sloan, Dallas-Fort Worth

While the suburban mega city is largely the product of unbridled real estate speculation, their existence establishes a new starting point for urban design—hopefully one that produces cities by nature. “Form follows performance” may replace the industrial preoccupation of the twentieth century and its priority for “function” that is damaging to the environment. It will take the effort of many, if not everyone’s, hands to get a grip on all the solutions that are needed. It is a purpose and priority on which all should agree.

What Cities Can Learn from Human Bodies

Nadine Galle, Amsterdam

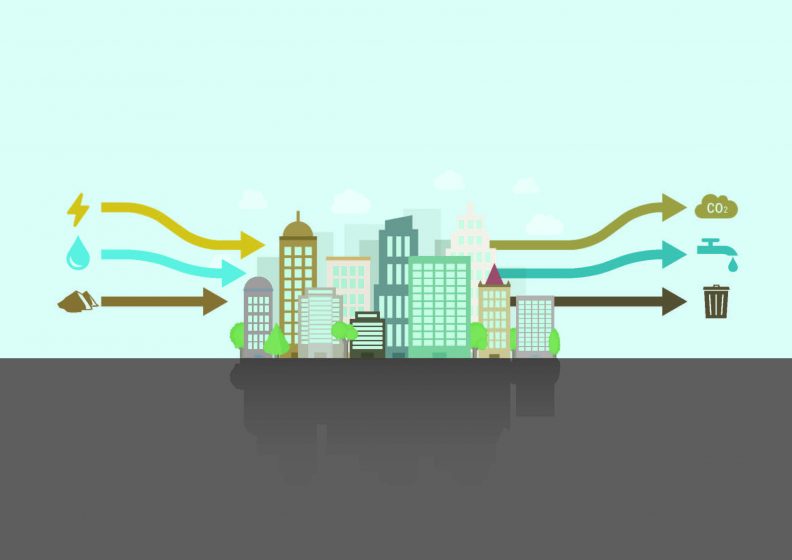

Urban metabolism is not only a powerful metaphor for better understanding our urban systems, but also the fundamental framework we need for accelerating the transition to sustainable cities. Like human bodies, cities require resources to function. They import or stock up on what they need, consume the resource, and then dispose of what is left over in the form of different types of waste. But one widely accepted definition of urban metabolism does not (yet) exist. Over the course of several generations, different disciplines and schools of thought have used this term to frame a range of findings.

Cities’ Quality of Life, Health, and Sustainability Are Defined by Access to Nearby Parks

Adrian Benepe and Benita Hussain, New York

It’s possible that many planners and civic leaders continue to undervalue parks as key pieces of a city’s ecological and social fabric. This is evidenced by how one in three in the United States lack access to a park within a 10-minute walk, leaving more than 100 million Americans deprived of easily accessed green space, creating a cascade of impacts on mental and physical health, and even economic opportunities for these cities. This is why The Trust for Public Land, in partnership with the Urban Land Institute, and the National Recreation and Parks Association, launched the 10-Minute Walk to a Park Campaign.

Reclamation and Mining: A Dangerous Fight for Sustainability in the Philippines

Ragene Palma, Manila

Campaigning and working for sustainability is a difficult and dangerous job. While various challenges already seem burdensome in the Philippines, especially for a developing country, we continue to face environmentally-damaging threats from “done deal” projects between our government and the Chinese government. As an environmental planner, I am very concerned about sustainability of our resources. Three advances are needed: more effort on environmental assessments, improved legislation, and inclusive planning.

Imagining Future Cities in an Age of Ecological Change

Ursula Heise, Los Angeles

Floating cities. Flying cities. Domed cities. Drowned cities. Cities that flip over once a day to expose different populations to sunlight. Cities underground, in the oceans, or in orbit. Cities on moons, asteroids, or other planets. Cities of memory, of surveillance, or of violence. Speculative fiction in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries has offered an enormous range of urban visions of the future, many of them dystopian, a few utopian, and quite a few somewhere in between. For good reason: Cities have taken on a new centrality for human futures.

This essay is the Introduction from TNOC’s new book—A Flash of Silver Green—on very short fiction about future cities.

From Wet Feet to a Tiny Food Forest—How These 4th Graders Transformed Their Schoolyard into a Tiny Food Forest

Marthe Derkzen, Amsterdam

This story begins on a grey afternoon in January 2018. Twenty-six 9 and 10 year-olds were nervously wobbling on their chairs in their classroom on the 1st floor of a primary school in the town of Ede the Netherlands. The sound of low whispers and hushed giggles, heads curiously turning to the door. We have come to realize that a greener, safer and healthier world starts at a young age and that the schoolyard is the perfect place to provide urban nature for everyone, regardless of any children’s home situation. The movement for green schoolyards is on!

Vegetating Tall Buildings

Gary Grant, London

Despite the success of some of these pioneering projects, the rise in popularity of lightweight green roofs in Europe and North America and the podium gardens of the high-rise cities of the Far East, the practice of establishing trees on taller buildings remains a curiosity and is still unusual. But that may be changing. Although there are some difficulties associated with growing trees and certain vegetation types on tall buildings, the success enjoyed by Hancock, Hundertwasser, and Boeri highlighted in this essay, shows that it is possible.

French Landscape Painters and the Nature of Paris—A review of Masterpieces of French Landscape Paintings from the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts Moscow

Patrick M. Lydon, Osaka

Any exhibition that starts with an 18th century tree hugger has me on a hook. If we learn anything from an exhibition such as “Masterpieces of French Landscape Paintings”, it might be that French landscape painters have a thing or two to teach us about urban nature over the centuries. Despite their lush depictions of natural scenery, French landscape painters were primarily Parisian urban dwellers. Biophiles, the lot of them too.

Water Sensitive Urban Design Goes Mainstream in Victoria, Australia

Meredith Dobbie, Victoria

Melbourne has long been at the forefront of sustainable stormwater management through WSUD. WSUD, in formal definition, is “the design of subdivisions, buildings and landscapes that enhances opportunities for at source conservation of water, rainfall detention and use, infiltration, and interception of pollutants in surface runoff from the block”.

Neither Above Nor Below

Neither Above Nor Below

Claire Stanford, Los Angeles

This story won 1st prize in TNOC’s flash fiction contest., It begins: A flash of silver-green in the water. That is all Hasan sees, but it is enough. He runs after, alongside, his small legs propelling him across the planks and platforms that crisscross the city. The wood once scratched underfoot, but it has gone smooth with time and wear, just as the soles of Hasan’s feet have grown thick and hearty, able to withstand all but the sharpest of splinters…

Biophilia Revived: How Do We Strengthen the Connection to the Natural Environment in a City Expanding in the Desert

Abdallah Tawfic, Cairo

Cairo’s share per capita of green spaces—1.7 m2/capita—is much lower than the international norms and standards. More than half of the city’s population only have 0.5 m2/capita; 70% of the population experience less than the city average of 1.7 m2/capita. In other words, the little green and open space there is concentrated in just a few neighborhoods. New ideas such as green roofs could add a decent amount to Cairo’s green spaces, given the huge amount of abundant flat concrete roofs. The idea has triggered the government’s attention in the form of two national campaigns.

Neighborhoods that Change in Non-linear Ways—Urban Planning for Succession

Neighborhoods that Change in Non-linear Ways—Urban Planning for Succession

Mathieu Hélie, Montréal

Behind the two fracture points of modern planning, NIMBYs and gentrification, is one fundamental question: should neighborhoods change? NIMBYs and anti-gentrification activists agree that they should not. The modern planning system was invented to enforce that agreement. If you wonder whether a struggle to add a few permissions allowing property owners to build studio rentals on their properties is worth the pain, realize what this change implies; it shifts the fundamental question of planning from should our neighborhood change to how should our neighborhood change.

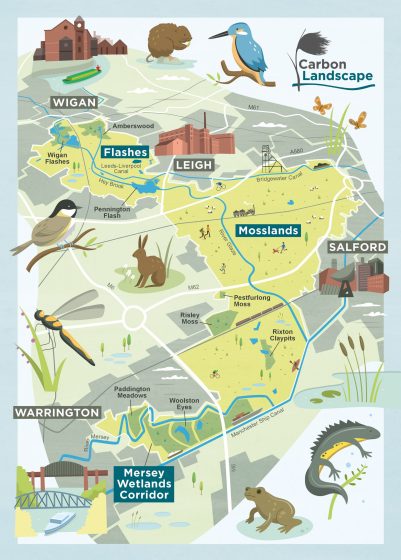

Nature Rebounding in the Peri-Urban Landscapes that the Industrial Revolution Left Behind: North West England’s Carbon Landscape

Janice Astbury and Joanne Tippett, Manchester

Less than an hour cycling out of central Manchester along the Bridgewater Canal takes you into a green and blue landscape. It only becomes clear that this is a post-industrial area when the infrastructure of a coalfield pithead rises up behind the trees. The vision for the Carbon Landscape? “It would have to be a thriving place, a green place, a place for people, for wildlife, for recreation, for health, all of those things.”

The TNOC content most read in 2019 was from 2016

(TNOC’s content tends to have a long shelf-life, and many older essays remain actively read.)

Graffiti and street art can be controversial, but can also be a medium for voices of social change, protest, or expressions of community desire. What, how, and where are examples of graffiti as a positive force in communities?

In many cities, graffiti is associated with decay, with communities out of control, and so it is outlawed. In some cities, it is legal, within limits, and valued as a form of social expression. “Street art”, graffiti’s more formal cousin, which is often commissioned and sanctioned, has a firmer place in communities, but can still be an important form of “outsider” expression. Interest in these art forms as social expression is broad, and the work itself takes many shapes—from simple tags of identity, to scrawled expressions of protest and politics, to complex and beautiful scenes that virtually everyone would say are “art”, despite their sometimes rough locations. What are examples of graffiti as beneficial influences in communities, as propellants of expression and dialog? Where are they? How can they be nurtured? Can they be nurtured without undermining their essentially outsider qualities?

With contributions from: Pauline Bullen, Harare; Paul Downton, Adelaide; Emilio Fantin, Bologna; Ganzeer, Los Angeles; Germán Eliecer Gómez, Bogotá; Sidd Joag, New York City; Patrick Lydon, San Jose & Seoul; Patrice Milillo, Los Angeles; Laura Shillington, Montreal

Leave a Reply