Introduction

about the writer

Claudia Misteli

Claudia is a social designer, communicator, and journalist who believes that care, creativity, and collaboration are key to building more just, vibrant, and nature-connected places. Born between Colombia’s coffee region and the Swiss Alps, she now lives in Barcelona, blending cultures and perspectives in her work. At The Nature of Cities, she co-leads European projects and TNOC Festival, sparking connections and meaningful action. Claudia also volunteers with the Latin American Landscape Initiative (LALI), helping amplify regional voices and build bridges across Latin America through storytelling, communications, and a deep love for people and place.

For too long, rural territories have been defined by external narratives — seen as places of tradition and stagnation, of romantic retreat or inevitable decline. But the people who live and work in these landscapes tell a different story.

The rural is not what it used to be. Was it ever? Across continents, a new rurality is emerging, shaped not by nostalgia but by reinvention. As Catalan writer and farmer Júlia Viejobueno illustrates in her book Quedar-se al Tros, working the land today is an act of both continuity and transformation: rooted in generations of knowledge yet shaped by contemporary challenges such as climate unpredictability and shifting rural economies.

What are cities without the rural? The food on our tables, the water in our taps, the materials that shape our homes—all rely on rural territories and the people who sustain them. Yet, policies, markets, and cultural perceptions often reinforce a rigid divide, overlooking the deep interdependencies between urban and rural territories.

What does it mean to sustain and reimagine rural life on its own terms?

How can rural territories be seen not as the city’s periphery but as central to a just, resilient, and interconnected world?

How do we move beyond simplistic urban-rural divides and acknowledge the fluid, interwoven realities of today’s landscapes?

What new models of governance, economy, and cultural expression are needed to support this transformation?

To embrace this new rurality is to let go of rigid lines.

It is to understand that resilience is not built in isolation, but in the weaving together of landscapes, stories, and dreams — across hills and highways, crops and screens, cities and fields.

The rural is not fading.

It is becoming something new.

Caterina Amengual Morro

about the writer

Caterina Amengual Morro

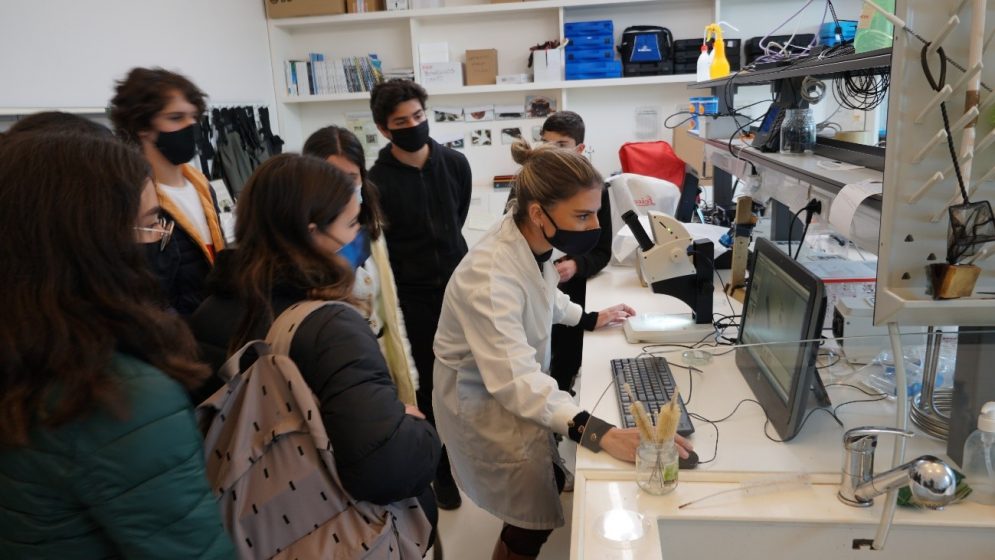

Caterina, PhD, is an environmental consultant and aquatic ecologist specializing in socio-ecological systems and sustainable water management. With over 20 years of experience in public administration, research, and consulting, she designs nature-based solutions for water, landscape, and ecological urbanism. She collaborates with the Interdisciplinary Ecology Group at the University of the Balearic Islands, among other institutions.

Entretejernos en el Territorio, Para Reconectar Con el Planeta

Las cerezas ya están grandes y verdes, hay que cubrir el cerezo con una red para que los pájaros no se las coman primero. Una de las cosas que más me fascina de convivir en el campo, es que cada cosa tiene su tiempo. Cuando haces la acción a tiempo, todo funciona, si se te pasa el momento, -plas!- ya hay que esperar al año siguiente. Lo mismo ocurre al segar, o plantar. El campo da y pide verdad y belleza.

La nueva ruralidad viene a enseñarnos a vivir, a reconectar con el planeta, a salir de la crisis climática en un viaje hacia el centro de la vida. He tenido la suerte de conocer grandes maestros de la ruralidad y poder escuchar a la gente que vive del campo es un placer de la vida que os invito a degustar. Y observo la ruralidad desde la isla de Mallorca, en el Mediterráneo, donde lo rural y lo urbano están muy cerca.

La lección es parar. ¿Cuanto tiempo puedes estar parado, sin hacer nada? El campo te invita a quedarte mirando una hoja de higuera, las estrellas, o observar el movimiento sutil del pájaro.

La lección es parar. ¿Cuanto tiempo puedes estar parado, sin hacer nada? El campo te invita a quedarte mirando una hoja de higuera, las estrellas, o observar el movimiento sutil del pájaro.

En la revolución industrial empezó la aceleración de los combustibles fósiles y el éxodo hacia las zonas urbanas. La consecuencia está en el calentamiento global y los altos costes ambientales del tranporte. La crisis climática nos obliga a replantearnos el volver al campo para aprender a alimentarnos mutuamente.

Vivir en el entorno rural es la oportunidad para volver a entender qué son alimentos desde su origen, o el sonido natural, sin ruido. Pero más importante todavía, entender el placer de quedarse en el mismo lugar por años, el disfrutar de una cotidianeidad en el que cada día es diferente.

El entorno rural tiene la aventura del sencillo disfrute. Descubrir la vida sencilla es ahora un lujo sorprendente y embriagador. Experimentar la autenticidad de la existencia es una puerta de entrada hacia la reconexión con lo que somos. Los ciclos naturales, cada años similares, cada día distintos, nos reconectan con esta esencia, donde cada gesto tiene una consecuencia: cavar la tierra, podar la parra, tejer fibras vegetales o recoger una sandía. El gesto tiene sentido en el lugar.

En la neo rurarlidad damos valor al conocimiento local. El que lleva décadas saliendo cada día al mismo trozo de tierra y cultivándolo, viviendo de sus frutos. Esta consciencia de la tierra es la que tiene que llegar a los humanos urbanos.

La dependencia del agua, es otra certeza necesaria. Conocer la fuente que te da de beber. Ser tú quien deriva la canal para captar el agua de lluvia, saber cuanta agua acumularás para pasar el cada vez más largo y más calido verano, esta es una soberanía humana básica.

La mezcla del conocimiento ancestral con las nuevas técnicas de agricultura regenerativa y creación de suelo fértil, es una fusión que me emociona, ya no es un secreto que podemos crear suelo.

Y podemos crear energía, saber de dónde cortar la leña que te calienta en invierno, es otra fuente de libertad.

Pero sobretodo la neo-ruralidad nos convoca a juntarnos, a hacer comunidad, ya que no tiene ningún sentido ni éxito la vida rural individual. De esta manera, nos entretejemos en el territorio con la comunidad con la que convivimos. Cuidamos lo que nos da sustento y lo celebramos en proximidad. Como el placer que da esperar a que las cerezas maduren, en un árbol que has plantado tu misma con tus vecinos y el sencillo disfrute de compartir las cerezas con los que más quieres.

Weaving ourselves into the land to reconnect with the planet

The cherries are already big and green; we need to cover the cherry tree with a net so that the birds don’t eat them first. One of the things that fascinates me most about living in the countryside is that everything has its time. When you act at the right time, everything works; if you miss the moment — snap! — you have to wait until the next year. The same happens when mowing or planting. The countryside demands and offers truth and beauty.

The new rurality comes to teach us how to live, reconnect with the planet, and find a way out of the climate crisis on a journey toward the heart of life. I have been lucky to meet great masters of rural life, and listening to people who live off the land is one of life’s pleasures that I invite you to savor. I observe rural life from the island of Mallorca, in the Mediterranean, where the rural and the urban are very close.

The lesson is to stop. How long can you stay still, doing nothing? The countryside invites you to simply gaze at a fig leaf, the stars, or observe the subtle movement of a bird.

The Industrial Revolution marked the start of the acceleration of fossil fuel use and the migration to urban areas. Its consequences include global warming and the high environmental costs associated with transportation. The climate crisis forces us to rethink returning to the land to learn how to nourish one another.

Living in a rural environment offers the opportunity to truly understand food from its origin and to hear the natural soundscape without noise. But even more importantly, it teaches the pleasure of staying in the same place for years, enjoying a daily life in which every day is different.

The rural environment holds the adventure of straightforward enjoyment. Discovering the simplicity of life has now become a surprising and intoxicating luxury. Experiencing the authenticity of existence opens the door to reconnecting with our true selves. Natural cycles, similar each year yet different every day, reconnect us to this essence, where every action has a consequence: digging the soil, pruning the vine, weaving plant fibers, or harvesting a watermelon. Every gesture makes sense in its place.

In the new rurality, we value local knowledge — that of someone who has spent decades tending the same piece of land every day and living from its fruits. This awareness of the land is what must reach urban humanity.

Dependence on water is another necessary certainty. To know the source that gives you water. To be the one who diverts the channel to capture rainwater and know how much water you will store to survive an increasingly long and hot summer is a basic form of human sovereignty.

The fusion of ancestral knowledge with new techniques of regenerative agriculture and fertile soil creation excites me; it is no longer a secret that we can create soil.

We can create energy—knowing where to cut the wood that will keep us warm in winter is another source of freedom.

But above all, the new rurality calls us to come together to form a community because rural life makes no sense and finds no success in isolation. In this way, we weave ourselves into the land alongside our community. We care for what sustains us and celebrate it close by. Like the pleasure of waiting for the cherries to ripen on a tree you planted yourself with your neighbors, and the simple joy of sharing the cherries with those you love most.

M’Lisa Colbert

about the writer

M'Lisa Colbert

M'Lisa Lee Colbert is a social scientist, and an urban farmer. She is currently working to improve access to locally grown produce year-round at an affordable price, in Montreal.

Go Deep: A Rurality Reimagined

I see the new rurality not so much as a return or going back — for me, it’s about going deep.

As the lines between city and countryside blur, we’re called to reimagine place, not as a binary, but as a braided system of care, innovation, and resilience. The question is no longer rural or urban — but how we root in both, drawing from each to build something new.

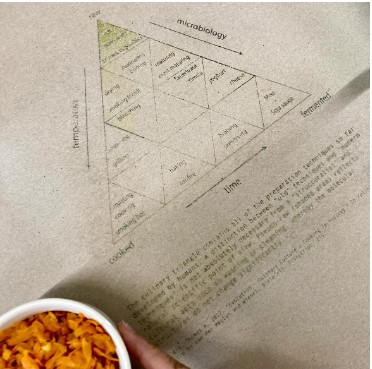

As an urban farmer in Montreal, I grow food in an urban storefront, not on acres of land. My work is rural in spirit where the ethic of this approach comes from old land logic: plant what you need, share what you can, waste nothing, and root your wealth in relationships. This is not a nostalgia project. It’s a living, emerging system that merges rural intention with urban reality.

In this view, to move beyond the urban-rural divide is to embrace hybridity. In this case, hydroponics and heritage, tech stacks and trust, towers and traditions. Achieving this is very much tethered to our will and imagination to push forward to design systems for people and the planet that respect both. Too often, we talk about scale as something vast — bigger farms, longer supply chains, and more. Economies of scale are framed as wide and sprawling — monocultures, mega-farms, mass production. But scale can also be dense, local, and intimate. Like a root. Like a microchip. Like a human heart: small in form, vast in function.

This is the kind of rurality we need now: not defined by geography but by intention and ethics. This shift in mindset changes everything. This means we stop measuring success by reaching and start measuring it by richness. Rural becomes not a place, but a practice: of stewardship, care, interdependence, and slowness. A rurality that shows up in storefront farms, alley gardens, office buildings, sidewalk markets, industrial enclaves, and kitchen co-ops. A rurality that moves through cities as memory and method — through stories passed down, and technologies passed forward.

To embrace this, we must let go of outdated divides and build ecosystems that are both grounded and adaptive. That means valuing rural knowledge not as old or obsolete but as radically future-facing. It means seeing urban spaces not as disconnected, but as fertile ground for new forms of rooted life. Equity in this reimagined landscape starts with design. When systems are built small and shared, not hoarded, they become spaces of belonging. When food is local, not in the nostalgic sense, but in the community sense — something you can see, touch, and know — it can’t help but become a common place. A real connector.

This new rurality won’t be built from a single direction and requires many hands and many voices. It will come from the spaces in between. From those who know how to braid scale with story. From those who understand that roots don’t ask permission to cross boundaries. They just grow — deep, and in every direction. We don’t need to stretch wider. We need to root deeper.

That’s where the future begins.

Saurav Dhakal

about the writer

Saurav Dhakal

Saurav Dhakal is a sustainability advocate, climate communicator, and social entrepreneur. As Director of Sustainable Growth and Innovation at Green Growth Group, he integrates Tourism, Energy, and Agriculture for sustainable impact. He co-founded StoryCycle, promoting ecological awareness through digital storytelling, and has coached youth-led green initiatives. An adventurer and climate champion, Saurav promotes sustainable living, local production, and nature-based solutions, believing in a future rooted in natural capital and community empowerment.

Redefining Rural Futures: Innovation, Resilience, and the Power of Local Markets

The rural-urban divide is becoming less relevant as rural areas are evolving and embracing new opportunities for resilience and innovation. Rural communities are not just places of tradition—they are becoming hubs of ecological stewardship, technological advancement, and self-determination. Instead of separating urban and rural spaces, we should focus on their interconnections, where rural areas play a vital role in shaping sustainable futures.

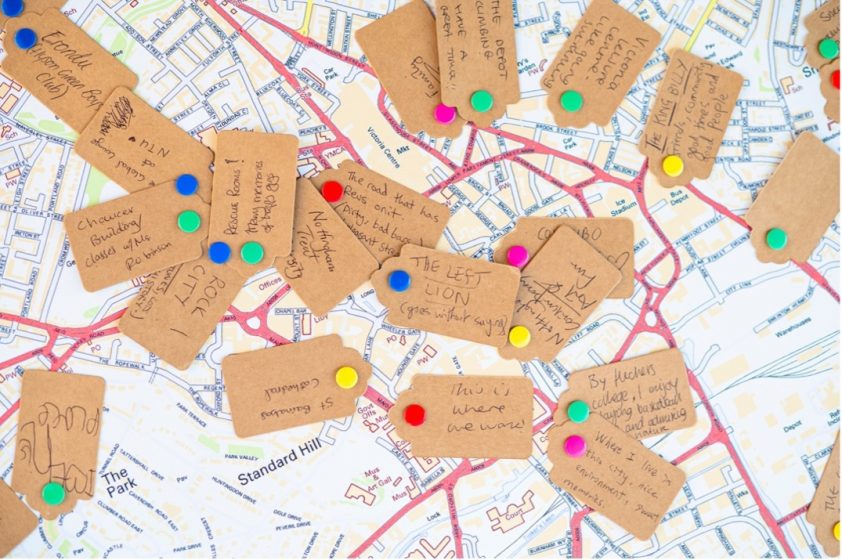

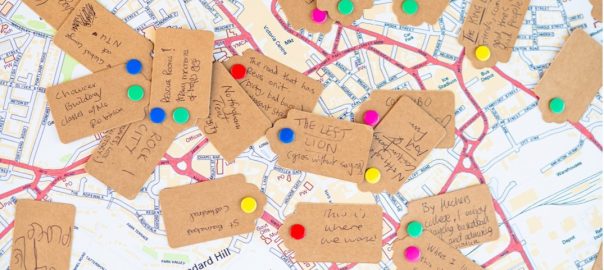

In my work across Nepal, especially through StoryCycle, Karesa, and DreamCities, I’ve seen how rural communities are using modern tools to innovate. Through DreamCities, we engage youth in community mapping, like the Bhiman project, where local stories and aspirations are shared online to help shape better urban planning. This initiative encourages youth to contribute to their communities’ sustainability, giving them a voice in the development process.

In my work across Nepal, especially through StoryCycle, Karesa, and DreamCities, I’ve seen how rural communities are using modern tools to innovate. Through DreamCities, we engage youth in community mapping, like the Bhiman project, where local stories and aspirations are shared online to help shape better urban planning. This initiative encourages youth to contribute to their communities’ sustainability, giving them a voice in the development process.

Karesa is focused on strengthening local market systems in rural areas. We work with farmers to implement traceability systems, helping them track food miles and reduce carbon footprints. By connecting farmers directly to urban markets, we create a farm-to-table model that boosts their income and ensures consumers get fresher, more sustainable products. This system eliminates middlemen, improving market access for rural farmers.

Karesa is focused on strengthening local market systems in rural areas. We work with farmers to implement traceability systems, helping them track food miles and reduce carbon footprints. By connecting farmers directly to urban markets, we create a farm-to-table model that boosts their income and ensures consumers get fresher, more sustainable products. This system eliminates middlemen, improving market access for rural farmers.

Local markets are crucial for bridging rural and urban economies. As these markets become more sustainable, they help rural communities build resilient economies that can withstand environmental and economic challenges. Karesa helps farmers access better markets, diversify their products, and meet urban demand. This leads to economic inclusion and strengthens rural-urban ties.

Local markets are crucial for bridging rural and urban economies. As these markets become more sustainable, they help rural communities build resilient economies that can withstand environmental and economic challenges. Karesa helps farmers access better markets, diversify their products, and meet urban demand. This leads to economic inclusion and strengthens rural-urban ties.

While rural areas are showing innovation, outdated policies often fail to recognize their needs. Extractive industries, climate challenges, and rigid policies still pose significant barriers to growth. To support rural resilience, we need governance models that understand rural complexities while fostering connections with urban areas. Policies must allow rural communities to thrive independently while engaging with urban spaces.

Rural areas are also reclaiming their cultural heritage. As cities become more homogeneous, rural communities are embracing their unique identities and blending them with modern innovations. Rural areas should not be seen as stagnant or backward but as vibrant spaces of culture, innovation, and resilience.

The future of rural areas is not about looking backward but embracing a new rurality that focuses on innovation, self-determination, and sustainable local markets. By supporting rural transformation, we can ensure that both rural and urban areas work together for a sustainable, equitable future.

References:

Dhakal, S. (2023). StoryCycle – Community Mapping in Bhiman. StoryCycle

Dhakal, S. (2023). Karesa – Empowering Rural Farmers Through Traceability Systems. StoryCycle

Global Environment Facility (GEF). (2021). Leveraging Local Knowledge for Sustainable Rural Development. GEF

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2020). Rural-Urban Linkages and Sustainable Development. UNDP

Juliana Gatti P. Rodriques

about the writer

Juliana Gatti P Rodrigues

Believing every tree is precious, Juliana Gatti uses her skills in Sustainability Design and Biodiversity Conservation to build sustainable cities. Leading the Instituto Árvores Vivas NGO, she promotes environmental education – teaching about nature to create social change and ensure healthy spaces. Her diverse work includes advising CONAMA (Brazil's environmental policy council) and contributing to the Resilient Green Cities Program.

Aprendizagem prática e integração: a diversidade das paisagens originais e a cultura da relação humana com o ambient

Pesquisas científicas multidisciplinares recentes, envolvendo biologia, botânica, antropologia e arqueologia, comprovaram a complexa composição e organização das paisagens na América Latina, utilizando tecnologias de ponta. Um exemplo notável é a confirmação de que povos ancestrais selecionaram, cultivaram e desenvolveram novos frutos, como o cupuaçu, para maior produção de polpa e alimento. Adicionalmente, foram reveladas cidades ocultas sob a floresta amazônica, com intrincadas redes de assentamentos interligados há cerca de 2.500 anos.

Ao longo de milênios, a profunda relação entre o ser humano e o planeta, seus biomas e suas características físicas estabeleceu processos de aprendizado e manejo, proporcionando melhores condições de vida a diversos grupos em diferentes territórios. Os povos originários sempre observaram atentamente áreas alagáveis, respeitaram matas ciliares, manguezais, campos de altitude e os ciclos naturais do fogo, da seca e da chuva. Essa integração se manifesta na maior conservação de áreas protegidas no Brasil, precisamente em territórios indígenas, quilombolas e de povos e comunidades tradicionais, que mantiveram relações equilibradas e respeitosas com o ambiente ao compreender a intrínseca ligação entre a saúde dos territórios e a saúde das populações.

A população mundial tem se concentrado de forma massiva em centros urbanos, atingindo no Brasil mais de 80%. No entanto, é crucial lembrar que os territórios urbanos estão inseridos em uma vasta e rica diversidade de biomas com suas características únicas. A degradação da paisagem natural e de sua biodiversidade acarreta a perda da conectividade entre fragmentos de áreas naturais, essenciais para a preservação de ecossistemas que sustentam a vida como a conhecemos, por exemplo impactando também mananciais, fontes de água, protegidos e limpos.

De forma acelerada, sistemas de produção extensivos, a monocultura, a especulação imobiliária e a exploração — muitas vezes ilegal — de recursos madeireiros e minerais têm destruído a qualidade ambiental fundamental à vida. O consumo desenfreado, inconsciente e irresponsável, impulsionado por uma dinâmica de vida que nos afasta das relações empáticas com o planeta e seus habitantes de todos os reinos, amplia esse distanciamento e reduz a preocupação destes impactos em uma escala sem precedentes.

O enfraquecimento dessa conexão vital cria uma oportunidade para que as vidas urbanas e rurais expandam seus pontos de contato, cultivando espaços onde emergem soluções; a resiliência floresce e a diversidade nutre o encontro entre saberes tradicionais e novas tecnologias. Embora a degradação ambiental rural também esteja em curso, nas cidades esse processo de alteração da saúde planetária já alcançou estágios insustentáveis. Contudo, a prática do trabalho manual e a conexão com o tempo natural nas atividades produtivas contribuem para a sustentabilidade e o equilíbrio entre o que se extrai, como se cuida e o que retorna aos sistemas naturais que sustentam a vida: energias, elementos, ciclos, estágios, interação ecológica e habitats únicos.

As desigualdades e injustiças, legados de uma história de ocupação, opressão e apropriação, ainda marcam profundamente a sociedade do Sul Global. Populações vulnerabilizadas, quando fortalecidas, oferecem caminhos, saberes e práticas valiosas capazes de promover o ressurgimento de uma qualidade de vida mais humana e empática nas cidades, começando pela segurança alimentar, sanitária e climática. As soluções baseadas na natureza surgem nesse contexto como uma ponte que conecta o fazer engenhoso e tecnológico com a leitura atenta do território, da diversidade da vida, dos saberes e da cultura local.

Toda intervenção e abordagem baseada na natureza representa uma oportunidade comunitária excepcional para aprendizado, comunicação, troca e aprimoramento dos processos de intervenção, integrando perspectivas de uma vida rural conectada ao ambiente urbano. A sociedade participativa e engajada traça novos caminhos para se organizar, fortalecer e conectar experiências, criando respostas bem-sucedidas que podem ser monitoradas, ampliadas e replicadas, adaptando-se às particularidades de cada território. Nessas implementações, é crucial incluir toda a diversidade de representações e vozes, desde gestantes e crianças na primeira infância até idosos e pessoas com deficiência ou condições especiais.

Ao construir essas novas pontes férteis e prósperas com humanidade e empatia, o reconhecimento de todas as vidas humanas, o acolhimento das situações desafiadoras e de sofrimento, e a expansão dessa comunidade unida para relações respeitosas com todos os seres vivos e sistemas naturais, definem o tom dessa integração e equilíbrio. Essa transformação emerge das sementes plantadas em corações e mentes, convertendo-se em sentimentos e atitudes mais justas, comprometidas e respeitosas com o mundo, de forma vibrante e alinhada com o surgimento de um novo tempo para as economias e valores socioambientais.

Practical Learning and Integration: The Diversity of Original Landscapes and the Culture of Human Relations with the Environment

Recent multidisciplinary scientific research, involving biology, botany, anthropology, and archaeology, has proven the complex composition and organization of landscapes in Latin America, utilizing cutting-edge technologies. A notable example is the confirmation that ancestral peoples selected, cultivated, and developed new fruits, such as cupuaçu, for greater pulp and food production. Additionally, hidden cities beneath the Amazon rainforest, with intricate networks of interconnected settlements dating back approximately 2,500 years, have been revealed.

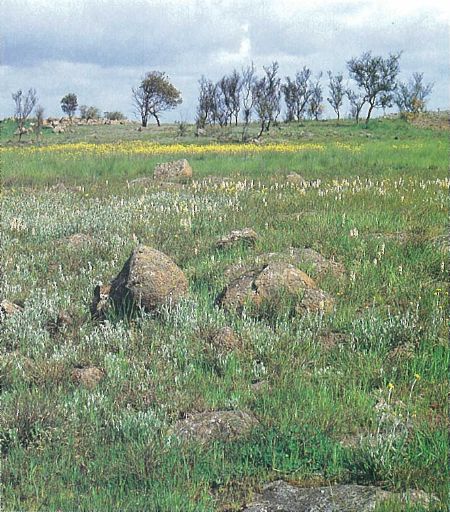

Over millennia, the profound relationship between humankind and the planet, its biomes, and its physical characteristics has established learning and management processes, providing better living conditions for diverse groups in different territories. Indigenous peoples have always attentively observed floodplains, respected riparian forests, mangroves, high-altitude fields, and the natural cycles of fire, drought, and abundant rain. This integration is evident in the greater conservation of protected areas in Brazil, precisely within indigenous, quilombola, and traditional peoples’ territories, who have maintained balanced and respectful relationships with the environment by understanding the intrinsic link between the health of the territories and the health of the populations.

The world’s population has been massively concentrating in urban centers, reaching over 80% in Brazil. However, it is crucial to remember that urban territories are embedded within a vast and rich diversity of biomes with their unique characteristics. The degradation of the natural landscape and its biodiversity leads to the loss of connectivity between fragments of natural areas, essential for the preservation of ecosystems that sustain life as we know it, for example, also impacting protected and clean water sources and springs.

At an accelerated rate, extensive production systems, monoculture, real estate speculation, and the — often illegal — exploitation of timber and mineral resources have been destroying the fundamental environmental quality necessary for life. Unbridled, unconscious, and irresponsible consumption, driven by a lifestyle that distances us from empathetic relationships with the planet and its inhabitants of all realms, amplifies this detachment and reduces concern for these impacts on an unprecedented scale.

The weakening of this vital connection creates an opportunity for urban and rural lives to expand their points of contact, cultivating spaces where solutions emerge; resilience flourishes, and diversity nurtures the encounter between traditional knowledge and new technologies. Although rural environmental degradation is also underway, in cities this process of altering planetary health has already reached unsustainable stages. However, the practice of manual labor and the connection with natural time in productive activities contribute to sustainability and the balance between what is extracted, how it is cared for, and what returns to the natural systems that sustain life: energies, elements, cycles, stages, ecological interaction, and unique habitats.

The inequalities and injustices, legacies of a history of occupation, oppression, and appropriation, still profoundly mark the society of the Global South. Vulnerable populations, when empowered, offer valuable paths, knowledge, and practices capable of promoting the resurgence of a more human and empathetic quality of life in cities, starting with food, health, and climate security. Nature-based solutions emerge in this context as a bridge connecting ingenious and technological practices with the careful reading of the territory, the diversity of life, local knowledge, and culture.

Every nature-based intervention and approach represents an exceptional community opportunity for learning, communication, exchange, and improvement of intervention processes, integrating perspectives of a rural life connected to the urban environment. A participatory and engaged society charts new paths to organize, strengthen, and connect experiences, creating successful responses that can be monitored, scaled up, and replicated, adapting to the particularities of each territory. In these implementations, it is crucial to include the full diversity of representations and voices, from pregnant women and early childhood children to the elderly and people with disabilities or special conditions.

In building these new fertile and prosperous bridges with humanity and empathy, the recognition of all human lives, the welcoming of challenging and suffering situations, and the expansion of this united community towards respectful relationships with all living beings and natural systems define the tone of this integration and balance. This transformation emerges from the seeds planted in hearts and minds, converting into fairer, more committed, and respectful feelings and attitudes towards the world, vibrantly and aligned with the emergence of a new era for socio-environmental economies and values.

Mariona Gabarró Rovira

about the writer

Mariona Gabarró Rovira

Mariona Gabarró Rovira is a sustainability strategist currently pursuing a master’s in Environmental, Economic, and Social Sustainability at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, with a specialization in Ecological Economics. Her interests include indigenous perspectives, Buen Vivir, and community-based approaches to ecological and social transitions.

Rethinking the Rural: Technology, Desire, and the Path to Buen Vivir

Rural and urban life have often been seen as completely separate. Rural was considered slow, disconnected, and traditional—while urban meant modern, fast, and innovative. But in today’s world, these ideas are changing. One of the main reasons is the democratization of information. Technology and access to knowledge are no longer limited to cities, and this is changing how people relate to each other and to the land.

During my travel through South America, I spent time with Indigenous communities in Ecuador such as the Shuar and the Kichwa. In a Shuar community, I met a young guy using TikTok to share everyday life in the forest. In these places, electricity is limited and the internet only works in certain areas—but still, technology and social media are finding their way in. This can be powerful: a tool to share identity, preserve culture, and build resilience in communities that are often invisible and deeply affected by environmental injustices.

However, technology also brings new tensions. As social media platforms spread urban lifestyles to rural areas, they can also shift local desires. In the Kichwa community, I heard people express feelings of poverty—not because of a lack of food or land, but because they didn’t own things like cars or smartphones. When the urban model is seen as the standard of success, it can create a sense of inadequacy, even in communities that hold deep, valuable knowledge and connection to their territory.

This imbalance is also visible in the opposite direction. From the urban side, the rural has often been seen mainly as a resource—especially in the Global North. A place that produces food, offers nature, peace, or clean air. This often comes with a process of commodification of nature, where landscapes are valued mainly for their use or their beauty, not for their intrinsic or relational meaning. Now, as city life becomes more stressful and unaffordable, more people are moving to the countryside. But often, this shift is driven by idealization. People seek nature and calm, but they bring with them urban habits and lifestyle expectations—often without adapting to the local rhythms or understanding the impact they may have on their new context. This disconnection can result in a lack of environmental care, or even conflict with local communities.

So how do we move forward?

I believe we need a new cultural narrative—one that helps us build bridges between rural and urban, tradition and innovation. For this, the Indigenous concept of Buen Vivir (good living) can be a guide. It proposes a different way of thinking about progress—not as endless growth, but as harmony. Harmony with oneself, with the community, and with the Mother Earth. Thinkers like Alberto Acosta describe Buen Vivir as a worldview that values reciprocity, collective care, and respect for all forms of life.

Arturo Escobar reminds us that territories are not passive—they are places of political action and imagination. In that sense, technology is not good or bad by itself. What matters is how we use it, and whether it helps us stay connected to the land and to each other.

If we want truly sustainable futures, we must listen to the knowledge that already exists in rural and Indigenous communities. We must stop idealizing or exploiting the rural, and instead walk together—towards shared well-being.

Note:

Several young Kichwa content creators are using social media to share their everyday life, territory, and culture from the Amazon. A few inspiring examples include:

- @pitiuruk – Visual stories and reflections on Kichwa territory, culture, and daily life.

- @helenagualinga – Environmental activism, Indigenous rights, and life in the Amazon, shared by a prominent Kichwa advocate.

- @yuturiwarmi – Community life, traditional practices, and Indigenous women’s voices from the Amazon.

These accounts show how technology can be used to strengthen identity, resilience, and environmental awareness—helping to build bridges between worlds.

Carla Gonçalves

about the writer

Carla Gonçalves

Carla Gonçalves is a Portuguese landscape architect, researching and advocating for landscape governance. She currently serves as the executive director of the Climate Centre in Póvoa de Varzim.

Landscapes Beyond Binaries

A new rurality is emerging—not nostalgic, but reinvented, experimental, and adaptive. And perhaps more importantly, it’s being lived and shaped from the ground up. This new rurality resists simple categories and reflects shifting, hybrid realities. To engage seriously with this transformation, we must move beyond binaries like urban versus rural, cultural versus natural, and land versus sea. These dichotomies no longer capture the fluid, interwoven realities of today’s landscapes—especially in places like Póvoa de Varzim, where I am writing from today, and in other geographies experiencing similar transitions.

Póvoa de Varzim is a municipality in Northern Portugal that defies easy classification. It’s a coastal town with beaches, fishing traditions, tourism, and intensive horticulture. Yet just a few kilometres inland, agro-forestry and dairy farming dominate, shaping rural patterns of life that persist, adapt, and evolve. Its proximity to Porto (35 km) adds further complexity: commuter flows, real estate pressures, and demographic shifts blur the lines between centre and periphery, urban and rural, coastal and inland.

In this context, the landscape is not merely scenery—it is a lived place. A dynamic space shaped by ongoing relationships between ecology, economy, culture, aesthetics, and care. Understanding this landscape demands that we abandon fixed boundaries and instead embrace it as a socioecological system—fluid, overlapping, and continually negotiated. Landscapes are collective processes, public goods shaped by the people who inhabit them, and constantly redefined through practice, memory, and imagination.

This perspective carries institutional implications. Socioecological boundaries rarely align with political ones. Rivers, forests, and coastlines don’t stop at municipal lines—nor do livelihoods, cultural ties, or environmental pressures. To govern such landscapes effectively, we need governance models that are adaptive, participatory, and capable of embracing complexity. This includes integrating diverse forms of knowledge—scientific, local, experiential—and acknowledging the multiple values that communities place on their landscapes.

Landscape thinking challenges the assumption that rural or urban areas are static, backward, or separate. There are no fixed boundaries in the landscape. Each unit is shaped by a unique combination of environmental, cultural, perceptual, and symbolic elements that transcend traditional divides. Yet governance structures often remain too rigid to accommodate this complexity. What’s needed are flexible governance arenas—spaces where diverse actors can co-produce knowledge, negotiate priorities, and imagine shared futures beyond administrative borders.

That also means committing to landscape justice: protecting livelihoods, honouring cultural heritage, ensuring equitable access to land and water, and amplifying voices that are often sidelined in landscape planning and decision-making processes. A concrete example of this shift in Portugal is the creation of the Centro do Clima da Póvoa de Varzim (Climate Centre of Póvoa de Varzim). A collaborative initiative involving the Municipality, the Parish of S. Pedro de Rates, and BIOPOLIS. The Climate Centre of Póvoa de Varzim embodies the principles of adaptive, co-produced governance, and it bridges scientific research, local knowledge, and institutional learning to confront the interlinked challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss, and territorial inequality.

By fostering knowledge co-production and promoting new governance models, the Climate Centre of Póvoa de Varzim reflects the complexity of today’s landscapes—where socioecological realities no longer align with political lines. It supports the evolving, hybrid nature of rural-urban territories, where diverse actors come together to shape shared futures. This is the new rurality in practice—not defined by nostalgia, but by reinvention and forward-looking possibility.

Ultimately, the question isn’t just how to support rural futures—but how we can learn from them. The blurred boundaries of territories like Póvoa de Varzim, where the urban meets the rural, the cultural meets the natural, the land meets the sea, and scientific knowledge meets political will, offer a compelling opportunity to reimagine what landscape governance and stewardship can look like—both now and in the years to come.

Patrick M. Lydon

about the writer

Patrick M. Lydon

Patrick M. Lydon is an American ecological writer and artist based in Korea whose seeks to re-connect cities and their inhabitants with nature. He is an Arts Editor here at The Nature of Cities.

The Warbler’s Question

Having recently moved from an inland city of 1.5 million people, to a city of 140,000 along the South Korean coast, I wake up each morning to a soundtrack that is unusual for me.

Just before sunrise here in the city of Tongyeong, a slight ruckus grows into a wild cacophony. Gulls cry as they head for the nearby port. Herons flap and squawk above them, on their way to the rice paddies over the hill. A Daurian Redstart drops into our garden, bows, flicks its tail.

Wonhang Morning Birds at 5:30am, Apr 19.mp3

Then from some unseen place, a Japanese Bush Warbler sings.

My head jerks around the landscape in a visual search for this bird, but they remain hidden.

This bird and I have a history. Over a decade ago, the melody of the Japanese Bush Warbler accompanied me on a multiple-year journey in Japan as I filmed and learned from the natural farmers there. In those lush fields, I witnessed something I did not think possible: dozens of productive farming ecosystems around the country with no imported nutrients or chemicals, no heavy machinery, and where all living beings were respected and given the right to live their lives.

These were places where humans made a point to support other forms of life as they went about theirs — and I thought, somehow, maybe the Bush Warbler knew it.

But this song — this bird — does not necessarily belong to the urban or the rural.

The Japanese Bush Warbler is selective, reclusive. It avoids concrete and traffic, yet it also avoids large-scale agriculture. The Warbler’s song is their message to the world, and they only sing it to places that are worthy — places where they know their message will resonate.

Somehow, they sing here, sending that long forte-piano-crescendo song across the water and through the hills that cradle this neighborhood.

Logically, I understand why. Tongyeong has an urban core, but it is largely a city of islands. Half of the island we live on is a national park. The sea surrounding us is a marine sanctuary. The road into this corner of the island is narrow, winding—it slows cars, invites stillness. This is a city that is at once urban, rural, and none of the above. But more so, there is a feeling here, that this particular part of the city remembers something most others have forgotten: how to be part of a living landscape.

In much of the rapidly urbanizing world — including most of Korea — urban planning typically sees nature as a “feature” or “ecosystem service”, something to be controlled and dialed in for the benefit of humans.

Whether we stand on asphalt or farmland, the question we ask is often the same: what can nature do for us humans? Rather than seeing ourselves inside of nature, we stand on the outside — we are the boss with the timecard and performance chart, demanding the rest of nature to prove its worth to us.

Most contemporary eco-urbanism still abides by this way of thinking.

So, it is something of a miracle to me that in this city, I wake up to the song of the Japanese Bush Warbler, a bird who sings a different tune, for a different kind of world. Their song acknowledges, that in this corner of the city, there are humans who put aside the time cards and performance charts, and who try at least, to accept their role as ecological beings.

Maybe the real reinvention isn’t about redefining rurality at all. Maybe the way to unite means, ends, places, and people with each other and the rest of nature is simply about listening.

About remembering how to belong to something bigger than ourselves.

About asking questions like a Bush Warbler:

Is this place worthy of singing to?

Dirk Madriles

about the writer

Dirk Madriles

Ultimately a farmer grounded in human-scale agriculture, farming operations, animal husbandry, and crop cultivation with the aim to produce real and healthy food that improves the wellbeing of people and the environment. Taking part in rural innovation, added value chains and responsible business models.

¿Donde se encuentra la frontera entre la urbanidad y la ruralidad?

Hasta hace poco tiempo, eran dos espacios distintos, mal conectados entre sí, en donde los unos y los otros tenían poca y mala información los unos de los otros, alimentando prejuicios y mitos en cada uno de los lados. La frontera entre urbanidad y ruralitud (o ruralidad?) se encontraba al final de las carreteras, o a la entrada de los pueblos, con muchos de estos pueblos con calles sin asfaltar. Habitantes de pueblos y habitantes de ciudades se tocaban el fin de semana, al rededor de las actividades de ocio, turismo gastronómico y vacacional. ¿qué tenían en común personas habitantes rurales y visitantes urbanos? Que compartían el espacio rural, durante unos pocos días del año (fines de semana y verano) obteniendo provecho mutuamente: unos obtenían descanso, alimentación, cultura y bienestar, los otros una fuente de ingresos indispensable para complementar sus actividades económicas y de sustento.

Pueblos y ciudades han coexistido en realidades paralelas, a ritmos distintos, dinámicas distintas, de manera autónoma e independiente los unos de los otros. Pero esa frontera invisible, que una vez se encontraba más cerca de los márgenes de las ciudades que de los pueblos, se ha ido desplazando hacia el corazón de los pueblos y más allá. Ahora, en la actualidad, la frontera de la urbanidad ha engullido los pueblos enteros. Y es muy intuitivo entender dónde se encuentra ahora.

Los flujos de intercambio de información (incluso monetarios) que han caracterizado la relación rural-urbana se encuentran en la cultura, el ocio y la alimentación, y ésta última, la alimentación, es la más paradigmática de todas para entender el lugar en el que se ha consolidado esta frontera invisible entre urbanidad y ruralitud: no hay más que abrir la nevera de las “cases de pagès” o de cada una de las familias productoras agricultoras y rurales, tanto en ambientes periurbanos como remotos; el reflejo de toda la comida que encontramos allí es el reflejo exacto de los bordes de la urbanidad que todo lo ha invadido. Allí se encuentra la frontera en la actualidad. Una mentalidad urbanocéntrica que se ha expandido, que los habitantes de los pueblos han adquirido como falso reclamo de modernidad, de acceso a un modelo de cultura uniforme, individualizado y mercantilizado. Lo rural no tenía valor y no se ha mantenido ni en los pueblos, en todo su casco urbano, que ya ha perdido su vestigio de ruralidad.

Y la urbanidad se ha extendido incluso fuera de los pueblos, siguiendo caminos sin asfaltar, hasta las mismas casas o masías aisladas de las últimas familias de productores agrarios profesionales en las que encontramos la misma gama de alimentos procesados y enpaquetados en plástico que encontraríamos en cualquier domicilio de una ciudad. los hábitos de consumo, de alimentos, de cultura, de ocio, ya son los mismos que para cualquier otra persona de ciudad. Ya no es que un habitante de ciudad no sepa como se producen los alimentos, es que la mayoría de personas habitantes de los pueblos tampoco. La frontera entre urbanidad y ruralidad se encuentra, precisamente en ese reducto de ruralidad que son las masías, ya ni siguiera en los pueblos.

Así pues, habiendo transitado el primer cuarto de siglo, identifico el último espacio de ruralidad, más allá de blbliotecas y folclore social, allí donde las personas todavía se alimentan con productos de verdad, donde las personas productoras todavía conocen cómo producir alimentos de la huerta, los campos y la granja, donde todavía se cocinan los platos a fuego lento a partir de ingredientes de al lado, cuando las personas, sea cual sea su procedencia (ciudad o pueblo) mantienen vivo el conocimiento sobre quién y cómo produce los alimentos que nos nutren.

Ahí no hay resiliencia ni seguridad, hay riesgo de extinción y pérdida irrecuperable de conocimiento ancestral. Hay ignorancia acumulada y demasiada tecnificación (intensificación + digitalización). Hay una falta terrible de honrar a las generaciones pasadas y una dificultad enorme en imaginar un futuro posible para las siguientes generaciones que no sea urbano.

Tal vez se trate de volver a mover el límite de la urbanidad-ruralidad hacia las ciudades, volver a plantar huertos y criar animales en las ciudades, traer el campo a los parques urbanos, escuelas, jardines, patios, y edificios y comunidades. Tal vez se trata de no olvidar de donde venimos y que la ruralidad tiene que estar presente en las ciudades, en las administraciones públicas, en los consejos de administración y en los centros de decisión. Tal vez necesitamos comprender que la urbanidad necesita de la ruralidad, y que ambas dimensiones están conectadas, obligadas a entenderse, reconocerse, y aprender mutuamente, para progresar conjuntamente.

Where is the boundary between urbanity and rurality?

Until recently, these were two distinct spaces, poorly connected, where each side had little and often distorted information about the other, fueling prejudices and myths on both sides. The boundary between urbanity and rurality (or ruralness?) was found at the end of the roads, or the entrance to villages, many of which still had unpaved streets. Townspeople and city dwellers would cross paths on weekends, centered around leisure activities, gastronomic tourism, and vacations. What did rural residents and urban visitors have in common? They shared the rural space for a few days each year (weekends and summer), mutually benefiting: one group gained rest, food, culture, and well-being, while the other secured an indispensable source of income to complement their economic and subsistence activities.

Towns and cities coexisted in parallel realities, at different rhythms, with different dynamics, functioning autonomously and independently from each other. But that invisible frontier, which once lay closer to the outskirts of cities than to the villages themselves, has shifted toward the heart of the villages—and beyond. Today, the boundary of urbanity has engulfed entire villages, and it is very intuitive to sense where it now lies.

The flows of information (and even monetary exchanges) that once characterized the rural-urban relationship—cultural activities, leisure, and food—reveal this shift most clearly through food, the most paradigmatic example for understanding where this invisible boundary between urbanity and rurality has solidified: just open the fridge in a casa de pagès (traditional farmhouse) or in the home of any farming family, whether in peri-urban or remote rural areas. The food found there is an exact reflection of the urban sprawl that has invaded everything. This is where the boundary lies today. It is a form of urban-centric thinking that has expanded, a mindset that villagers have adopted as a false marker of modernity—of access to a standardized, individualized, and commercialized culture. Rurality lost its value and has not even been preserved in the towns’ urban centers, which have already lost any real trace of rural life.

Urbanity has spread beyond the villages, along dirt roads, reaching isolated farmhouses (masías) where the last families of professional agricultural producers live—and even there, we find the same array of processed and plastic-packaged foods as in any urban household. Consumption habits—of food, culture, leisure—are now the same as those of any city dweller. It’s not just that a city resident no longer knows how food is produced; the majority of villagers don’t either. The boundary between urbanity and rurality now lies precisely in the few remaining rural strongholds—the masías—and no longer even in the towns.

Thus, having crossed into the first quarter of this century, I identify the last spaces of true rurality not in libraries or social folklore, but where people still feed themselves with real products, where producers still know how to grow food from gardens, fields, and farms, where meals are still slowly cooked with ingredients sourced nearby—where people, regardless of whether they come from the city or the countryside, keep alive the knowledge of who grows the food that nourishes us and how they do it.

There, there is no resilience or security—there is risk of extinction and irretrievable loss of ancestral knowledge. There is accumulated ignorance and an excess of technification (intensification + digitalization). There is a terrible lack of honoring past generations and an enormous difficulty imagining a possible future for the next generations that is not urban.

Maybe it’s about pushing the boundary between urbanity and rurality back toward the cities—reintroducing gardens and animal husbandry in urban environments, bringing the countryside into city parks, schools, gardens, courtyards, buildings, and communities. Maybe it’s about not forgetting where we come from, about recognizing that rurality must have a presence within cities, public administrations, corporate boards, and decision-making centers. Maybe we need to understand that urbanity depends on rurality and that both dimensions are connected, bound to recognize, understand, and learn from each other in order to move forward together.

Sarah Mahoney, Sil Van de Velde, and Kana Chan

about the writer

Sarah Mahoney

Sarah is a cultural anthropologist with her graduate work completed from the University of Oslo. She carried out fieldwork funded by National Geographic Society in depopulated mountain villages in Japan to examine rural revitalization. Her research interests include lifestyle migration, post-growth imaginaries, and degrowth in rural Japan.

about the writer

Sil Van de Velde

Sil is passionate about education, conservation, and tourism development. He has been involved in projects with communities like the Saharawi and Dusun people to research the potential of international mobility to create awareness around (environmental) injustice and posthumanist worldviews. Sil is a co-founder of INOW, a social enterprise, with a mission to build a community of people who care about creating a circular, waste-free society.

about the writer

Kana Chan

Kana Chan is a writer and educator. She is the co-founder of INOW, an educational program based in Kamikatsu, Japan’s first "Zero Waste Village". Her work explores how immersive learning can inspire conversations about the global waste crisis and sustainability.

What if rural wasn’t a place?

In Japan, a new rural reality is emerging. As (young) urban migrants move from cities to depopulating villages, they begin to live differently: more intentionally and more relationally. So, what if rural wasn’t defined by geography (not by how far it is from the city, as it’s often understood), but instead by how we live?

In Japanese, the word kurashi refers to “a way of life”. Kurashi is not only a collection of lifestyle choices, but a deeper orientation toward time, values, and relationships. To understand rural, in this sense, is to rethink how we relate to people and to place.

Contemporary Japan is increasingly described as a muenshakai or a “relationless society”. Japan is centralized in Tokyo, one of the largest cities in the world, with a population of over 37 million. In contrast, the village of Kamikatsu has just over 1,300 residents. Yet despite Tokyo’s density and status, many people feel deeply isolated from themselves, from one another, and from the environment. Urban life, driven by capitalist ideals of speed, convenience, and individualism, can lead to disconnection and a loss of purpose.

Contemporary Japan is increasingly described as a muenshakai or a “relationless society”. Japan is centralized in Tokyo, one of the largest cities in the world, with a population of over 37 million. In contrast, the village of Kamikatsu has just over 1,300 residents. Yet despite Tokyo’s density and status, many people feel deeply isolated from themselves, from one another, and from the environment. Urban life, driven by capitalist ideals of speed, convenience, and individualism, can lead to disconnection and a loss of purpose.

Turning our attention to rural Japan may offer lessons on how to restore connection, belonging, and care in contemporary life. Kamikatsu is a small mountain town in Shikoku Island known for its zero-waste ambitions to reduce and recycle all of our waste. In Kamikatsu, rural life is grounded in relationships of care and reciprocity. To understand the rural is to recognize that society needs to be relationally oriented.

While cities are often viewed as centers of technological and economic progress, rural places like Kamikatsu are also becoming sites of innovation—driven by collaboration, care, and creativity. From the town’s pioneering Zero Waste system to a local brewery transforming malt waste into liquid fertilizer, and a company developing biodegradable textiles from forestry byproducts, innovation here is deeply rooted in place. What’s emerging is not a divide between rural and urban, but a fluid and interwoven relationship where ideas, people, and practices co-create new ways of living and working.

The government, too, is in transition. With limited resources and a shrinking tax base, it struggles to maintain basic infrastructure and services. In response, a new generation of residents are stepping in to form collectives, share responsibility, and experiment with alternative forms of local governance. This transition brings challenges, but it also opens space for meaningful (inter)generational exchange of knowledge, skills, and perspectives.

Traditional values of resourcefulness, reciprocity, and stewardship are interwoven with urban practices of design, architecture, and inclusiveness. Long-standing traditions are being reimagined such as the annual rethatching of kayabuki roofs, now sustained through the support of volunteers. New forms of living are also taking shape, as remote workers find ways to stay connected to cities while also contributing to the local community. As traditional schools face closure, experimental models of education emerge in their place. While many still see the countryside as static, young migrants arrive not to consume a way of life, but to co-create kurashi or way of life.

Traditional values of resourcefulness, reciprocity, and stewardship are interwoven with urban practices of design, architecture, and inclusiveness. Long-standing traditions are being reimagined such as the annual rethatching of kayabuki roofs, now sustained through the support of volunteers. New forms of living are also taking shape, as remote workers find ways to stay connected to cities while also contributing to the local community. As traditional schools face closure, experimental models of education emerge in their place. While many still see the countryside as static, young migrants arrive not to consume a way of life, but to co-create kurashi or way of life.

Azby Brown, author of the book Just Enough, illustrates how villages in Edo-period Japan (over 250 years ago) were built on interdependence. Farmers, artisans, and households survived by helping each other. Society also lived within their ecological means and people were guided by principles of reuse and resourcefulness. That mindset and practice still echoes in Kamikatsu today.

Azby Brown, author of the book Just Enough, illustrates how villages in Edo-period Japan (over 250 years ago) were built on interdependence. Farmers, artisans, and households survived by helping each other. Society also lived within their ecological means and people were guided by principles of reuse and resourcefulness. That mindset and practice still echoes in Kamikatsu today.

What’s emerging in rural Japan isn’t a return to the past. Urban migrants are crafting lives shaped by new values, reshaping the meaning of the kurashi in contemporary Japan. Rurality has become a site of experimentation for sustainable futures.

By turning our attention to rural Japan, it might help us restore a sense of connection, belonging, and care. Perhaps rural isn’t only a place but a way of being where we reconnect and reimagine how to live well with others and with nature.

Seema Mundoli and Harini Nagendra

about the writer

Seema Mundoli

Seema Mundoli is an Assistant Professor at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru. Her recent co-authored books (with Harini Nagendra) include, “Cities and Canopies: Trees in Indian Cities” (Penguin India, 2019), "Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India's Cities" (Penguin India, 2023) and the illustrated children’s book “So Many Leaves” (Pratham Books, 2020).

about the writer

Harini Nagendra

Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Sustainability at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India. She uses social and ecological approaches to examine the factors shaping the sustainability of forests and cities in the south Asian context. Her books include “Cities and Canopies: Trees of Indian Cities” and "Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India's Cities" (Penguin India, 2023) (with Seema Mundoli), and “The Bangalore Detectives Club” historical mystery series set in 1920s colonial India.

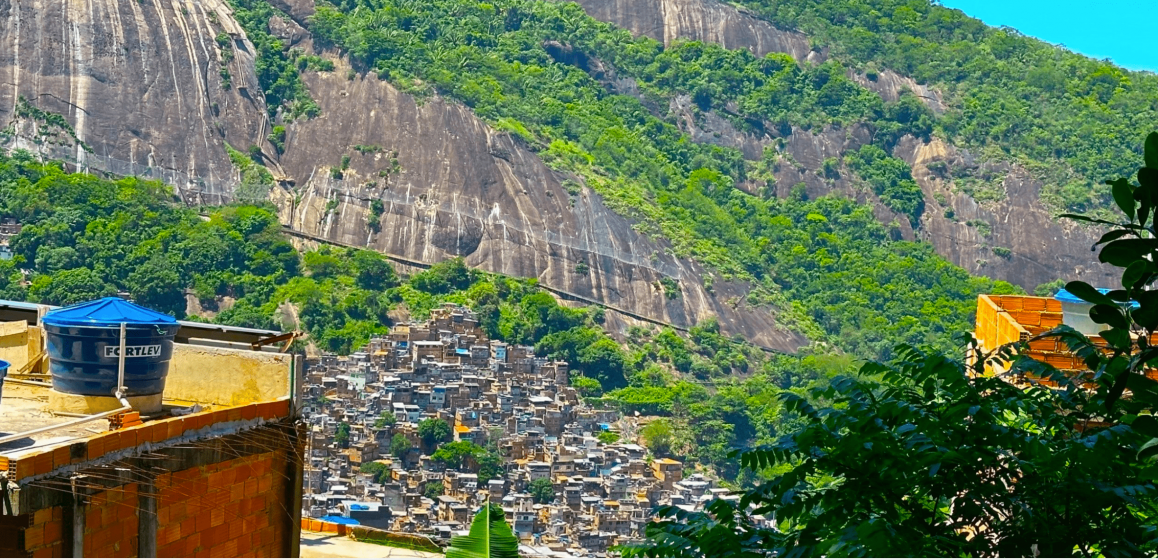

An extremely dynamic urbanization process is underway in the Global South, and this is most visible at the rural-urban fringe. In many parts of India, the peri-urban, at first sight, seems a dystopian space. In metropolitan cities of India, glass-fronted windows of software firms look out into agricultural farms, herds of livestock navigate rush-hour traffic on four and six-lane highways, and traditional fishers ply coracle boats on lakes alongside urban residents who circumambulate the periphery for recreation. The sprawl of the urban into the rural provides economic opportunities and employment for urban and rural migrants from different socio-economic classes but at the expense of ecosystems and other natural resources.

The rural-urban fringe is a no-man’s land, absent from urban plans and rural governance schemes. No one seems to care about the adverse impacts of urbanization on ecosystems such as lakes, ponds, and tanks, or wooded groves and avenue trees. These blue and green spaces were once commons that are now being converted, degraded, or transformed in use and in perception: with visible consequences.

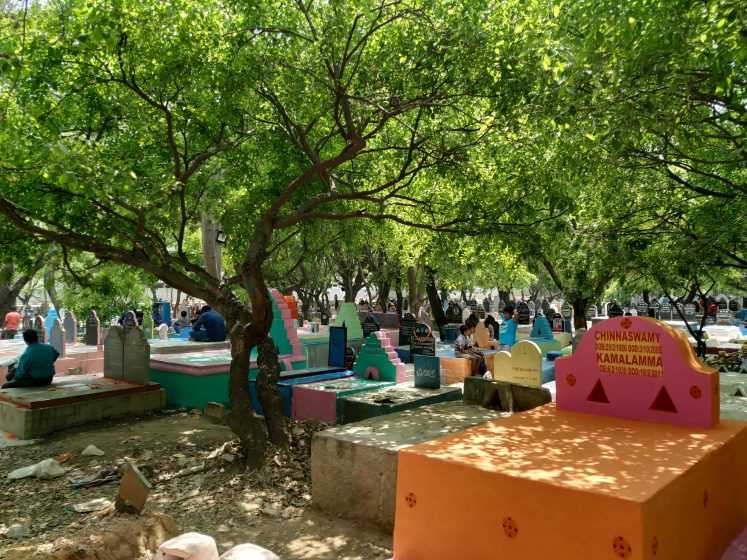

In one study in eastern Bengaluru, we had documented 302 commons in 46 peri-urban locations; 20 of these sites were in an urban municipality boundary while 26 were under the local village administration. The commons we studied included lakes, ponds, wooded groves, remnant grazing lands, and cemeteries, but all had been impacted by urban growth. Of the 90 wooded groves we surveyed, 62 had been converted to built space (including schools, community buildings, toilets, and housing for economically weaker sections), while 26 were badly degraded, and used as a waste dump piled high with construction debris and garbage. Only two of the groves were in good condition. Similarly of 31 ponds we studied, 24 had been built over. Of 99 grazing commons, 83 had been converted into software parks, industrial areas, and housing colonies. Cemeteries were relatively well protected, with 45 of 49 original sites still existing, even though several were in a degraded state. Of the 33 lakes in our study, 21 were in relatively good condition, eight were degraded with hyacinth overgrowth, dumping of garbage, and not much water, while four had been built over.

Even where commons remain, we find changes in perception and use. Commons are no longer seen as community resources that are used and managed by the community but as State property ― their care becoming the responsibility of the State. Until recently, rural commons supported livelihood and subsistence use, but with urbanization, their conversion into landscaped parks with ticketing, timings, and security guards have alienated traditional village users and the urban poor.

We began this research in 2015. Since then, the city has further urbanized. Bengaluru now has a population of 14.4 million. Many of the city’s wealthy residents live in expensive layouts, while others occupy low-income housing in the rural-urban fringe, and either travel to work in the city centre, or in newly established workplaces at the periphery. The loss of peri-urban commons is compounded by issues of poor waste management, faulty drainage, and lack of sanitation. The shifting baseline syndrome results in new urban migrants unable to imagine a time when this zone of rural and urban looked any different. At the same time, the local communities residing here are forced to adapt at a rapid rate to the environmental changes that have impacted their traditional way of life and interactions with commons.

This is not a story unique to Bengaluru but is played out across expanding metropolitan cities and urbanising towns across the country. The question for India as well as the Global South is how can cities change the trajectory from one of an increasingly dystopian development to move towards a more environmentally sustainable future? What kind of existing governance structures can be leveraged for better protection of what is left of the commons? How can a sense of place be fostered, helping people care for nature and making them stewards of the environment? This is not going to be easy ― especially when employment generation and economic development continue to be encouraged at the cost of the environment.

Our hope for the future lies in developing awareness about the existence of commons, their long history of local protection by communities, and the need for new, re-shaped communities in the peri-urban to form new relationships with old commons. It is not easy for a diverse, heterogeneous, inequal group of urban stakeholders ― children and adults, migrants and traditional residents, wealthy and poor, computer engineers and grazers ― to find a way to come together, much less to collectively imagine a future for the commons. Yet there is no better time than now.

Steward Pickett

about the writer

Steward Pickett

Steward Pickett is a Distinguished Senior Scientist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York. His research focuses on the ecological structure of urban areas and the temporal dynamics of vegetation.

Beyond the Urban and the Rural

Cities have been set off from their rural surroundings since time immemorial (1). Even in some cities today, there may be stretches of the old wall or surviving guard towers to remind us of the historic distinction. Even where the walls have been entirely removed, their shadow is visible in the form of close-in ring roads, in streets named “Wall”, districts named “Stockade”, or even wide tree-lined boulevards, which originally overlay the destroyed bulwarks or ramparts in some cities. Going further back, the idea of cities as demarcated sacred precincts, from which many people and certain activities were excluded, relies on a sharp distinction between city and non-city.

Rural or wild places have, of course, have been the “other” set against the urban boundary. Before industrialization in the West (e.g., England, Northern Europe, and North America), rural areas were primarily engaged in agricultural production, possessed internal markets and exchanges, and were autonomously governed. Several economic and political trajectories disrupted the rural networks beginning in the 1700s (2). Rural systems began to serve urban economies through migration of people to work in urban factories, the production of piece goods for urban markets, and the Parliamentary consolidation of rural land holdings to serve urban investments. This ongoing transformation was so significant that by 1968 Lefebvre (3) (translated to English in 1970) could write,

“Society has become completely urbanized. … The urban fabric grows, extends its borders, corrodes the residue of agrarian life. The expression, ‘urban fabric’, does not narrowly define the built world of cities, but all manifestations of the dominance of the city over the country.”

Lefebvre’s view of transformation between rural and urban space may still honor the ancient dichotomy too much.

While all this urban transformation was underway, most ecologists continued to value and investigate places that they assumed to be pristine, undisturbed, wild, or at least to lack obvious signs of human intervention. Cities, as the epitome of human intervention, were downright reviled by the majority of ecologists. Never mind that the supposed pristine nature of many ecological research sites would prove an illusion (4). Fortunately, there were ecological urban iconoclasts in Europe, Asia, and even a small number in the US (5–11). It took a long time for the ecologists’ gaze to shift from the wild and rural to the urban (11, 12). The occasional ecological glances at cities, suburbs, and exurbs began to be consolidated into interdisciplinary research platforms and long-term research projects during the 1990s (13–15). But this shifted gaze may still suffer from the problem of dichotomization of city and country.

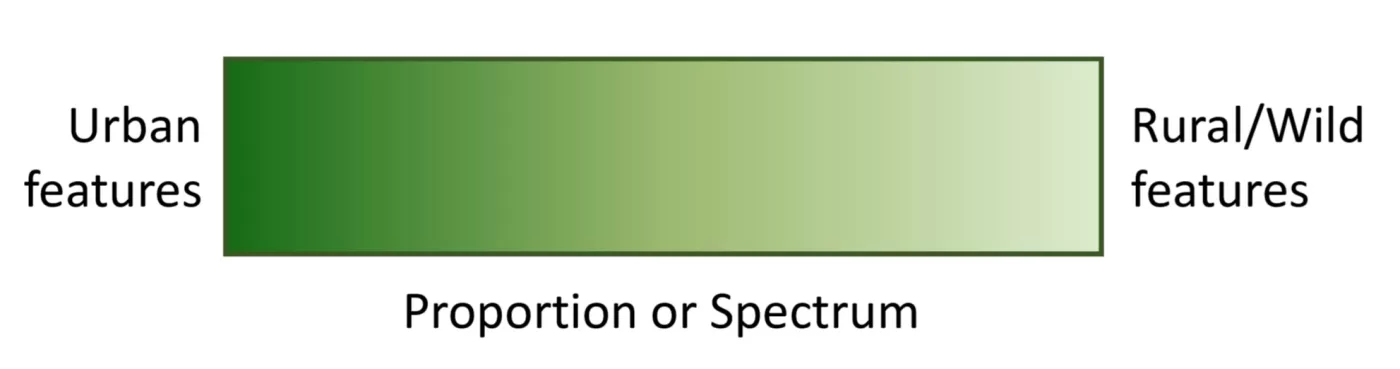

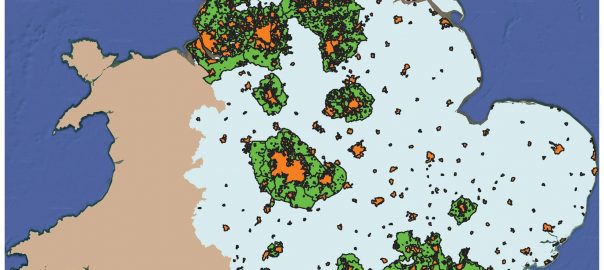

As urban social-ecological research matured, it has began to explore urban systems as though urban and rural weren’t just polar opposites (17–20). The fundamental assumption of this alternative, non-binary approach is that urban and rural are actually mixed with each other in various places. Therefore, there is a conceptual continuum of mixtures of urban and rural features in any location. If urban were to be represented by dark green, and rural represented by very pale pastel green, the mixtures of urban and rural features would be represented by all the intermediate bands of color between the extremes.

Pure urban and pure rural might be discernable at some places in a landscape, but so would many places that mix urban versus rural livelihoods, lifestyles, and cultural expectations. Connections, some quite local, and others spanning the globe, would continuously or episodically remake the mixtures of technologies available, investment or disinvestment, human populations, and biota (21). The hybrid conditions would be manifest in particular places, that is in ecosystems. It is crucial to recognize that what Lefebvre (22) might call “space” or urban designers, social scientists, and activists (23, 24) might call “place,” are to urban ecologists human ecosystems. Places are the nexus of the impacts and fluxes involved in livelihood, lifestyle, and the technologies and fluxes of connectivity. These places are social-ecological systems that mediate and are altered by the interacting fluxes.

Pure urban and pure rural might be discernable at some places in a landscape, but so would many places that mix urban versus rural livelihoods, lifestyles, and cultural expectations. Connections, some quite local, and others spanning the globe, would continuously or episodically remake the mixtures of technologies available, investment or disinvestment, human populations, and biota (21). The hybrid conditions would be manifest in particular places, that is in ecosystems. It is crucial to recognize that what Lefebvre (22) might call “space” or urban designers, social scientists, and activists (23, 24) might call “place,” are to urban ecologists human ecosystems. Places are the nexus of the impacts and fluxes involved in livelihood, lifestyle, and the technologies and fluxes of connectivity. These places are social-ecological systems that mediate and are altered by the interacting fluxes.

This new view of the urban-rural dichotomy acknowledges the ideal end members of urban and rural, but calls attention to the rich variety of intermediate, mixed structures and processes. With so much research effort in the past having been focused on the extremes, or on questions of where is the boundary between the two, there is an immense open horizon for understanding the complex real world and relevant practice.

If we follow in Lefebvre’s tradition, we might say that “the urban in the sense of an inclusive, hybrid realm, is the new rural”. Such a view resonates with those who call for recognizing “planetary urbanization” (25–27). Without denying the value of what the urbanized planet view promises, there may also be value in exploring a refined view that focuses on mixture and hybridity. In essence, the question becomes, What might be gained in taking seriously that our inhabited, built, exploited, and preserved systems are coproduced spaces (28–30)? Here are some more specific questions that follow that idea. What aspects of the rural remain, emerge, or are reinvented in the city, or more inclusively, urbanized regions (both socially and ecologically)? Can the mixtures of urban and rural features be retooled to reinforce the benefits of each, while reducing their detriments and hazards? Will thinking of urbanity/rurality as complementary and hybridized conditions help obviate the problems of holding rural and urban in opposition? Can “urbanity” be harnessed to promote these changes in concept and in practice? The continuum of urbanity provides a tool to get beyond the urban-versus-rural dichotomy.

References:

- L. Mumford, The City In History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects (Harcourt, New York, 1961).

- A. Sevilla-Buitrago, “Urbs in rure: historical enclosure and the extended urbanization of the countryside” in Implosions/Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization, N. Brenner, Ed. (jovis Verlag, Berlin, 2014), pp. 236–259.

- H. Lefebvre, The Urban Revolution (University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2003).

- W. Cronon, Uncommon Ground : Rethinking the Human Place in Nature (W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 1996).

- T. M. Airola, K. Buchholz, Species structure and soil characteristics of five urban forest sites along the New Jersey Palisades. Urban Ecology 8, 149–164 (1984).

- S. Boyden, “The ecological study of human settlements – lessons from the Hong Kong Human Ecology Programme” in Human Ecology and the Development of Settlements, J. O. Jones, Ed. (Plenum, New York, 1976), pp. 93–99.

- I. Kowarik, Herbert Sukopp – an inspiring pioneer in the field of urban ecology. Urban Ecosyst, doi: 10.1007/s11252-020-00983-7 (2020).

- O. L. Loucks, “Sustainability in urban ecosystems: beyond an object of study” in The Ecological City: Preserving and Restoring Biodiversity, R. H. Platt, R. A. Rowntree, P. C. Muick, Eds. (University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, 1994), pp. 49–65.

- H. Sukopp, “On the early history of urban ecology in Europe” in Urban Ecology: An International Perspective on the Interaction between Humans and Nature, J. Marzluff, E. Shulenberger, W. Endlicher, M. Alberti, G. Bradley, C. ZumBrunne, U. Simon, Eds. (Springer, New York, 2008), pp. 79–97.

- J. Wu, W.-N. Xiang, J. Zhao, Urban ecology in China: Historical developments and future directions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 125, 222–233 (2014).

- M. J. McDonnell, “The history of urban ecology: an ecologist’s perspective” in Urban Ecology: Patterns, Processes, and Applications, J. Niemela, Ed. (Oxford University Press, New York, 2011), pp. 5–13.

- S. E. Kingsland, The Evolution of American Ecology, 1890-2000 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005).

- S. E. Kingsland, “Urban Ecological Science in America: The Long March to Cross-Disciplinary Research” in Science for the Sustainable City: Empirical Insights from the Baltimore School of Urban Ecology, S. T. A. Pickett, M. L. Cadenasso, J. M. Grove, E. G. Irwin, E. J. Rosi, C. M. Swan, Eds. (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2019), pp. 24–44.

- N. Grimm, J. M. Grove, S. T. A. Pickett, C. Redman, Integrated Approaches to Long-Term Studies of Urban Ecological Systems. BioScience 50, 571–584 (2000).

- J. M. Grove, S. T. Pickett, From transdisciplinary projects to platforms: expanding capacity and impact of land systems knowledge and decision making. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 38, 7–13 (2019).

- S. T. A. Pickett, M. L. Cadenasso, J. M. Grove, C. H. Nilon, R. V. Pouyat, W. C. Zipperer, R. Costanza, Urban Ecological Systems: Linking Terrestrial Ecological, Physical, and Socioeconomic Components of Metropolitan Areas. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 32, 127–157 (2001).

- C. G. Boone, C. L. Redman, H. Blanco, D. Haase, J. Koch, S. Lwasa, H. Nagendra, S. Pauleit, S. T. A. Pickett, K. C. Seto, M. Yokohari, “Reconceptualizing land for sustainable urbanity” in Rethinking Urban Land Use in a Global Era, K. C. Seto, A. Reenberg, Eds. (MIT Press, Cambridge, 2014), pp. 313–330.

- Dawazhaxi, W. Zhou, W. Yu, Y. Yao, C. Jing, Understanding the indirect impacts of urbanization on vegetation growth using the Continuum of Urbanity framework. Science of The Total Environment 899, 165693 (2023).

- A. K. Hahs, Urban megaregions and the continuum of urbanity—embracing new frameworks or extending the old? Ecosystem Health and Sustainability 2, e01201 (2016).

- K. C. Seto, A. Reenberg, C. G. Boone, M. Fragkias, D. Haase, T. Langanke, P. Marcotullio, D. K. Munroe, B. Olah, D. Simon, Urban land teleconnections and sustainability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, 7687–7692 (2012).

- W. Zhou, S. T. A. Pickett, T. McPhearson, Conceptual frameworks facilitate integration for transdisciplinary urban science. npj Urban Sustainability 1 (2021).

- H. Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Blackwell, Oxford, 1991).

- D. Hayden, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes and Public History (MIT Press, Cambridge, 1995).

- L. Nishime, K. D. Hester Williams, Eds., Racial Ecologies (University of Washington Press, Seattle, 2018).

- N. Brenner, Theses on Urbanization. Public Culture 25, 85–114 (2013).

- N. Brenner, “Introduction: urban theory without an outside” in Implosions/Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization, N. Brenner, Ed. (jovis Verlag, Berlin, 2014), pp. 14–30.

- T. Elmqvist, X. Bai, N. Frantzeskaki, C. Griffith, D. Maddox, T. McPhearson, S. Parnell, P. Romero-Lankao, D. Simon, M. Watkins, Eds., Urban Planet: Knowledge towards Sustainable Cities (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2018; https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/urban-planet/05E1CEDF6B9DF4E4B95AB8B4474C3C71).

- A. Rademacher, M. L. Cadenasso, S. T. A. Pickett, From feedbacks to coproduction: Toward an integrated conceptual framework for urban ecosystems. Urban Ecosystems 22, 65–76 (2019).

- A. Rademacher, M. L. Cadenasso, S. T. A. Pickett, Ecologies, One and All: Singularity and Plurality in Dialogue. Environmental Humanities 15, 128–140 (2023).

- A. Rademacher, K. Sivaramakrishnan, Eds., Places of Nature in Ecologies of Urbanism (Hong Kong University Press, ed. 1, 2017; https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1k3s9dt).

Silvia Quarta

about the writer

Silvia Quarta

Silvia is a drylands restoration practitioner and trainer. Born in the north of Italy, her home is in the dry, arid and wild south of Spain. She is currently involved in the Quipar Watershed restoration project, aimed at restoring 30,000 ha of land around La Junquera. Her role is creating spaces for people in the territory to reconnect with the landscape and foster a culture of care and restoration.

Sometimes I find myself in awe. In front of the world outside of myself, outside of my own bubble.

I’m sitting on a train between Murcia and Barcelona. It takes me 6:30 hours and it costs me more than a 1:30 hour flight. Which many people would have preferred.

And I’m in awe. Most people don’t wonder: what is the impact of this?

But I’m a horrible environmentalist too.