A reading of names. A procession. Placing flowers on memorials. Music. Moments of silence. Tolling of bells.

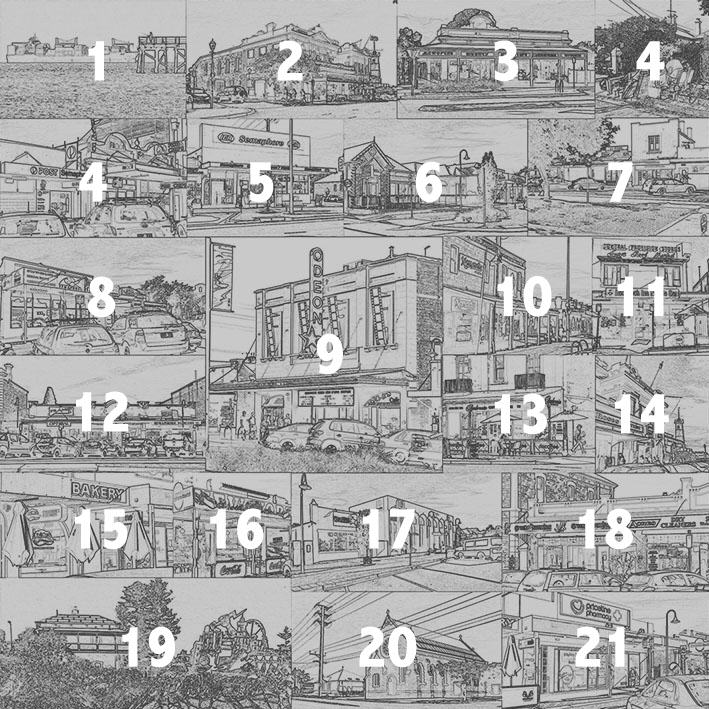

Certain abiding symbols and gestures give structure to our memorial remembrances. In particular, we have come to expect a ritual formality and consistency at the World Trade Center site for remembering September 11, 2001. But how do we mark the day at the hundreds of smaller, community-based memorials across the region and the country? These memorials are set in town parks, beaches, waterfronts, and civic grounds. They typically feature etched stones and evoke the healing power of nature with trees, shrubs, and flowers; each of the sites described below has had an event every year since 2001.

This work is part of our longitudinal research through the Living Memorials Project, which seeks to understand how people use nature and shape landscapes as restorative and reflective symbols and practices in remembrance of September 11, 2001. (To read more about the ongoing national research, see a prior TNOC blog post). A team of researchers conducted a collaborative ‘event ethnography’ of anniversary remembrances at six different community-based memorials throughout the New York City region on September 11, 2015. Event ethnographies are research efforts to document and analyze events; they are often used to cover large-scale, global meetings such as UN negotiations or conventions. But in this case, we conducted a dispersed event ethnography at local memorial remembrances throughout the region. We attended memorial events as participant observers documenting who attended, what the program was, what narratives framed the event, and how plants were used on the site. We wrote field notes, took photographs, and conducted a group debrief about our impressions and reflections, including notable patterns and exceptions.

Overall, we find that these memorial spaces are serving as sites of social meaning for local communities of friends, neighbors, and co-workers that are animated through formal events and everyday use. While many of the same rituals that are used at the national memorials are used at these locales, we find that activities and narratives vary with the creators of and audience for the site. Some are patriotic in tone, some call for peace, some call for a “war on terror”, some center on the emergency responders, and some focus on the local community.

Presented in chronological order of the time of the event (below), we offer a series of brief snapshots of how these memorial events occurred.

As night fell on September 11th at many of these local, hometown memorials distributed throughout the tri-state area of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, they were united under a common sky that, for a brief time, was aglow with Tribute in Light, two solid streams of light emanating from the September 11th Memorial and the former site of the Twin Towers in lower Manhattan.

As researchers, we reflect on our own experiences traveling through smaller towns and communities over the years. Sharing stories with our families and friends. Listening and learning as others recount their successes and setbacks in creating these special spaces in their own communities. We find that the light continues to shine in many places throughout the region as people come together in their own time and fashion to remember, to reflect, to continue on, and to pass on traditions to future generations.

We find that nature’s elements—such as an ocean view, a grove of trees, a symbolic ‘survivor tree,’ or a single rose—accompany us and serve as touchstones on a journey of land-marking and remembrance.

* * *

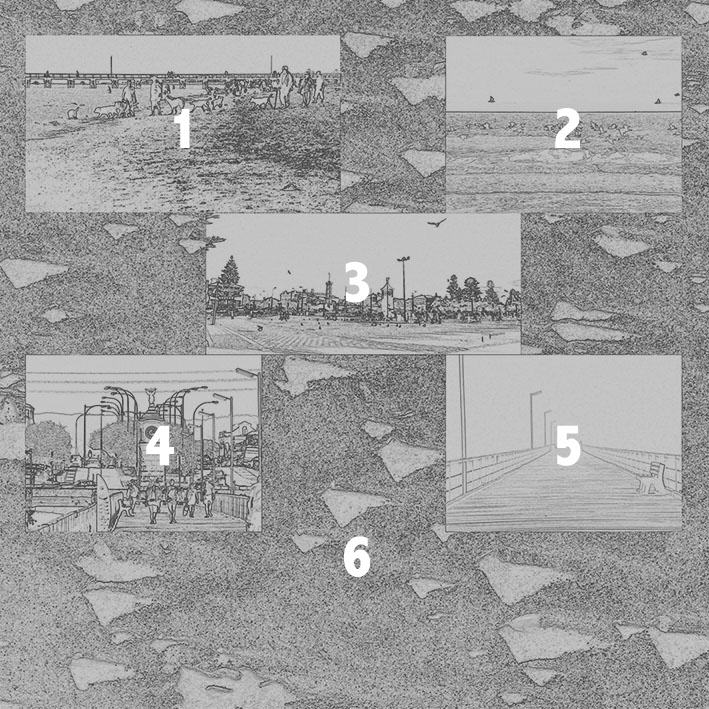

Connecticut’s Living Memorial, Sherwood Island State Park, Westport, CT: September 10, 5:30pm

Approximately 150 people gathered on the shore of the Long Island Sound to pay respects and remember residents of Connecticut who perished on September 11, 2001. Created just six months after the event occurred, this site is the state’s memorial to September 11th; as such, state officials, including the Governor and Lieutenant Governor, were in attendance, as well as representatives from the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection and the former Office of Family Support. In addition to patriotic songs and a color guard, the event featured a glee club performance of the song “Bridge Over Troubled Water” as requested by one of the organizers who is a September 11 family member. The organizers noted the therapeutic nature of creating the memorial and organizing this event. There has been a passing of the torch among several different project leaders who oversee the stewardship of the memorial and the event with continuity.

Nature symbolism is incorporated into the “Tree of Serenity”, a large sculpture of leaves, blossoms, and vines made from the cladding of the former World Trade Center and mounted on the park pavilion wall. During the ceremony, we were all invited to lay white roses on the etched marble memorial abutting the water’s edge. The site manager noted the challenges with maintaining a memorial situated so directly in the path of salt spray and tidal incursions, but the ongoing maintenance of the trees and plaques at sacred space is something to which the park remains committed.

Jacobi Medical Center, Bronx, NY: September 11, 8:30 am

Set on the hospital grounds and nestled into a wooded hillside, this site serves as a memorial to all victims from the Bronx, NY. It reflects Jacobi Medical Center’s ethos as a place that serves the community and promotes health and well-being. On September 11, the trauma center was prepared to receive survivors who, sadly, never arrived. But the hospital played a role in treating emergency responders. The event was attended by local hospital staff and administration—in lab coats, scrubs, and suits—many of whom were involved in the creation of the memorial. They were joined by their Community Advisory Board and numerous representatives of local public officials. The staff and advisory board provided the introductory remarks, the musical program (including Jacobi choir members singing Amazing Grace), the benediction, and a poem. Although public officials were acknowledge and thanked, they were not invited to speak.

A brief 30 minute ceremony included a moment of silence when the first plane hit; during that time you could hear the wind rustling, observe dappled sunlight through the trees, and watch commercial planes flying overhead. Being immersed in the natural setting was the goal of the site’s architect, who is retiring this year but noted that this memorial was the most meaningful project that she ever designed. The ceremony closed with everyone placing white carnations on the memorial. Though memories fade with time, one of the speakers noted that as long as she is alive, she is committed to continuing the tradition of holding September 11th remembrances.

A brief 30 minute ceremony included a moment of silence when the first plane hit; during that time you could hear the wind rustling, observe dappled sunlight through the trees, and watch commercial planes flying overhead. Being immersed in the natural setting was the goal of the site’s architect, who is retiring this year but noted that this memorial was the most meaningful project that she ever designed. The ceremony closed with everyone placing white carnations on the memorial. Though memories fade with time, one of the speakers noted that as long as she is alive, she is committed to continuing the tradition of holding September 11th remembrances.

Rockaway Tribute Park, Queens, NY: September 11, 8:30am

Approximately 200 people gathered in and around a small, triangular-shaped waterfront parcel on Jamaica Bay, including an array of FDNY and NYPD members, so many of whom live on the Rockaway Peninsula. Across the bay, the changed skyline of Lower Manhattan is visible from this memorial, which was created where people stood and witnessed the events of that day 14 years ago. The ceremony had few speeches, and focused on music, tolling bells, and reading of names. A procession of bagpipes was lead into the park by a four-man color guard, a new addition to the ceremony this year. Family and community members placed red roses at the memorial mosaic and steel relic from the World Trade Center site. Previously, the site had been flooded and damaged by Hurricane Sandy and was quickly repaired. Building upon this historical commitment, a NYC Parks Department administrator spoke about future repairs and improvements to the site. Stewardship of the site is also an ongoing act of care; every Tuesday morning, volunteers gather to weed, clean, and plant the site, marking the time when the planes hit the Twin Towers.

September 11 Family Group Memorial, Brooklyn, NY: Sept 11, 4:00pm

This fully bilingual service honored the memories of those of Russian descent who perished on September 11, 2001. Set in Asser Levy Park in Coney Island, the memorial features an inscribed plaque, benches, weeping willow—and a recently-planted ‘survivor tree’ that was grown from the surviving callery pear rescued from and returned to the World Trade Center site. It was clear that many in attendance had participated in prior years, as we observed that the procession “worked like clockwork”, with attendees lining up to place their flowers at the monument. The lead site steward seemed to be known and greeted by all of the hundreds in attendance—primarily adult and elderly residents of Russian descent as well as a number of local elected officials. The speeches called upon those assembled to “never forget” the memory of September 11, 2001, making parallels to the moral imperative never to forget what transpired in the Holocaust.

Glen Rock Assistance Council and Endowment (GRACE) Memorial at Veterans Park, Glen Rock, NJ: September 11, 6:30pm

For just a bit longer than usual, the NJ Transit commuter train lingered with its doors open as the train operators observed and paid respects to the town memorial service at the park directly adjacent to the train station. On a warm, late-summer Friday night, about 200 town residents—young and old—took time to reflect and remember. We gathered in front of a semi-circle of 11 plum trees that were planted in memory of the 11 victims from Glen Rock. GRACE always holds their event at this same time to allow family members who attend the service at the former World Trade Center site to then return home and participate in the Glen Rock service. Every victim’s name on the monument was adorned with bouquets of yellow flowers, a color that organizers chose because it symbolizes remembrance and being reunited. We were invited to process through the monument, holding white candles that were handed out and lit by the Boy Scouts.

The overarching theme of all the speeches and remarks focused on one word: community. In their brief and humble remarks, the Trustees invoked the Native American tradition of ‘wampum,’ which was originally used not as currency but to record and narrate history. Offering the ceremony as a gift, they joined together to retell the story of that day and related events in their community. This space was created by, for, and with the Glen Rock community by a committed set of nonprofit trustees focused on support for the September 11 family members, the survivors, and others in the Glen Rock community who experienced grave loss through acts of terrorism.

Babylon Hometown Memorial, Babylon, NY: September 11, 6:45pm

Much like the Rockaways, this coastal town in the middle of Long Island is home to many firefighters and first responders, over 100 of whom filled the walkways and sidewalks in full dress regalia. Bagpipes, patriotic music, and invocations from a Protestant minister and a Catholic priest shaped the program. This memorial is situated directly on the coastal dunes of the town beach, a setting that all the September 11 family members—and town residents in general—remember fondly. In addition to honoring each of the 48 victims from the town of Babylon, the memorial was designed to re-vegetate and enhance the dune ecosystem to support native flora and fauna to be more resilient to future floods. The site is dotted with native grasses, goldenrod, cedars, Rosa rugosa, and other hardy plants for the coastal setting. During the event, so many yellow sunflowers had already been handed out and placed at the memorial plaques that they had run out by the time we reached the front of the procession line. As the sun set, the fire trucks drove away, and beach goers strolled the sand to enjoy the last few hours of their Friday night.

* * *

Lindsay K. Campbell, Erika S. Svendsen, Heather McMillen, Novem Auyeung, Rachel Holmes, Michelle Johnson, & Renae Reynolds

New York City

About the Writer:

Erika Svendsen

Dr. Erika Svendsen is a social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station and is based in New York City. Erika studies environmental stewardship and issues related to hybrid governance, collective resilience and human well-being.

About the Writer:

Heather McMillen

Heather McMillen is the Urban & Community Forester with the Hawaiʻi Department of Land & Natural Resources.

About the Writer:

Novem Auyeung

Novem Auyeung is a Senior Scientist, Division of Forestry Horticulture & Natural Resources, NYC Parks. Novem guides conservation, research, and monitoring priorities for the Division.

About the Writer:

Rachel Holmes

Rachel Holmes is a conservation education specialist with The Nature Conservancy’s Forest Health Protection Program.

About the Writer:

Michelle Johnson

Michelle Johnson is a research ecologist with the USDA Forest Service at the NYC Urban Field Station.

About the Writer:

Renae Reynolds

Renae Reynolds is a Project Coordinator at the US Forest Service Urban Field Station in New York.

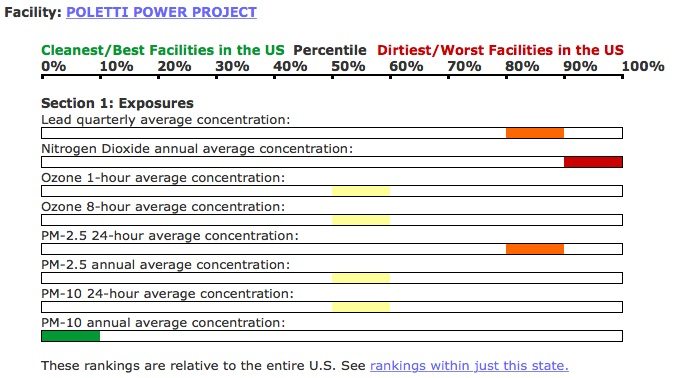

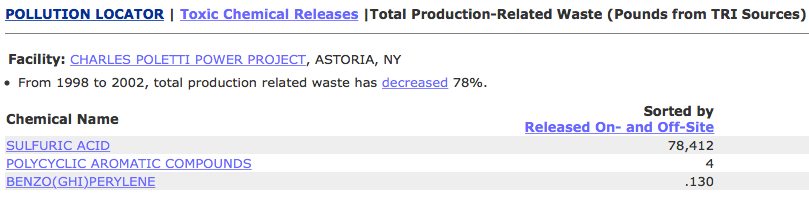

Beginning operation in 1977, the 885 megawatt facility was named for New York’s 46th Governor Charles Poletti. If there is anything in a name, the Poletti facility had an auspicious one. Charles Poletti graduated from Harvard Law School, served on the New York State Supreme Court, and been elected New York’s Lieutenant Governor alongside Governor Herbert H. Lehman. Poletti had the distinction of being the first Italian-American governor in the United States (albeit serving

Beginning operation in 1977, the 885 megawatt facility was named for New York’s 46th Governor Charles Poletti. If there is anything in a name, the Poletti facility had an auspicious one. Charles Poletti graduated from Harvard Law School, served on the New York State Supreme Court, and been elected New York’s Lieutenant Governor alongside Governor Herbert H. Lehman. Poletti had the distinction of being the first Italian-American governor in the United States (albeit serving

In my

In my

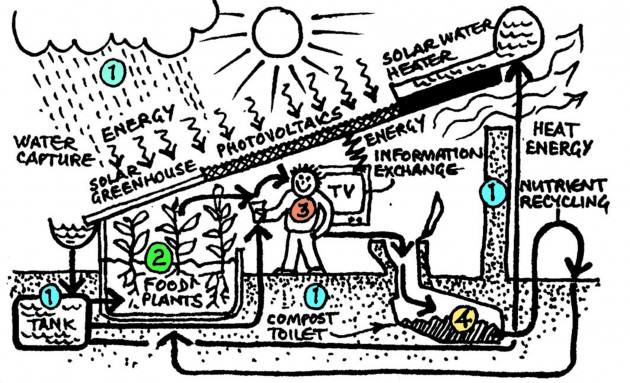

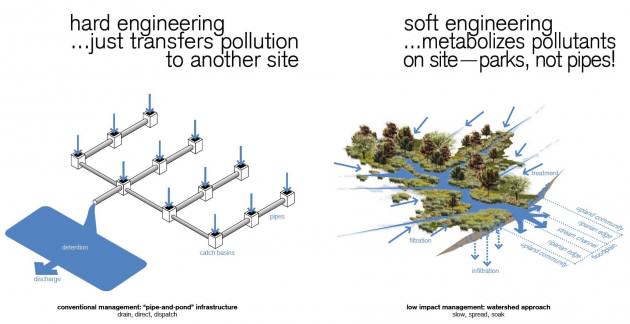

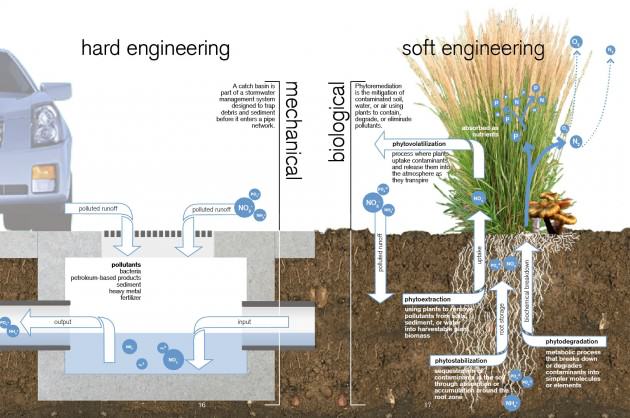

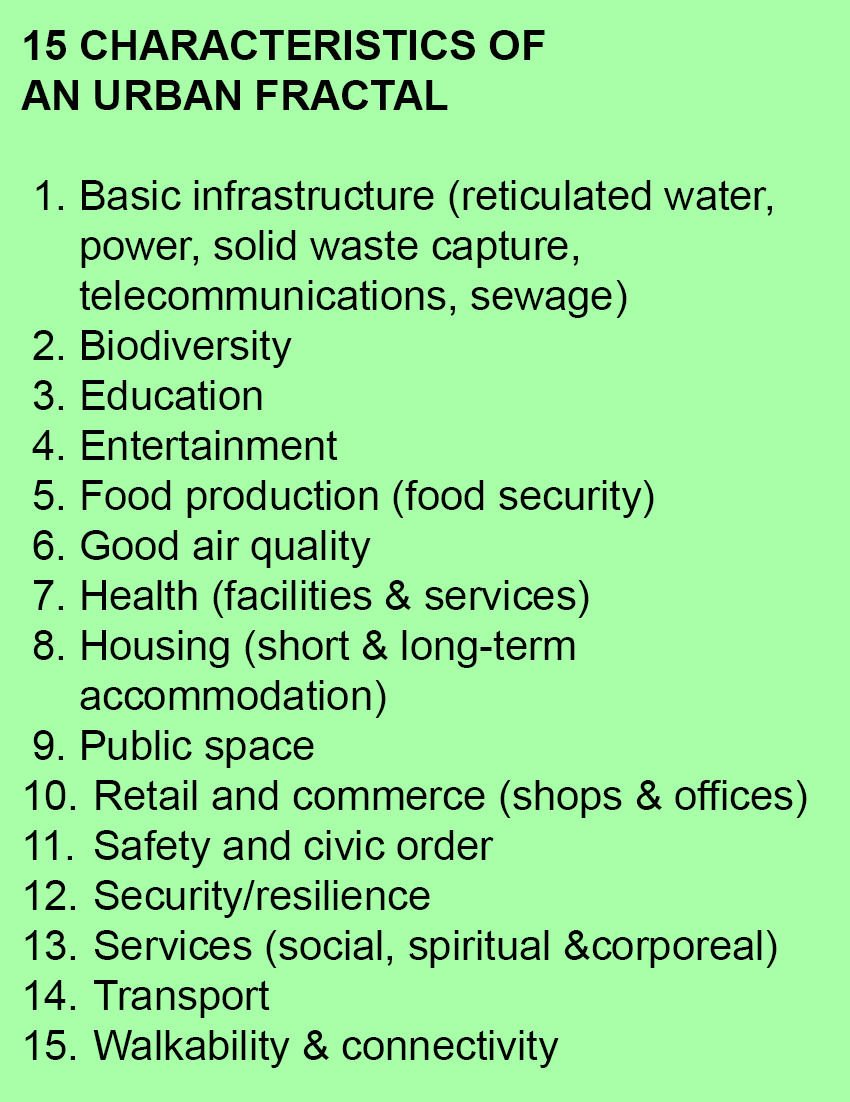

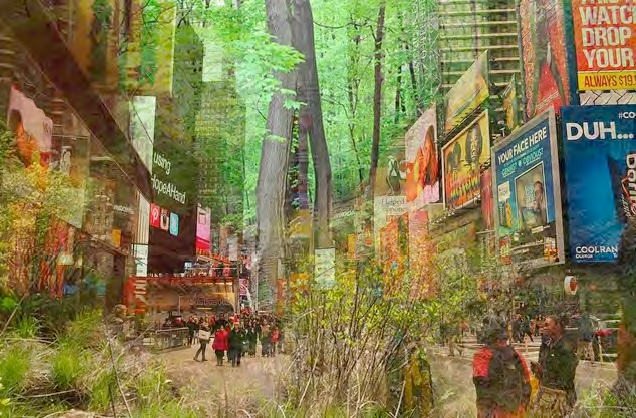

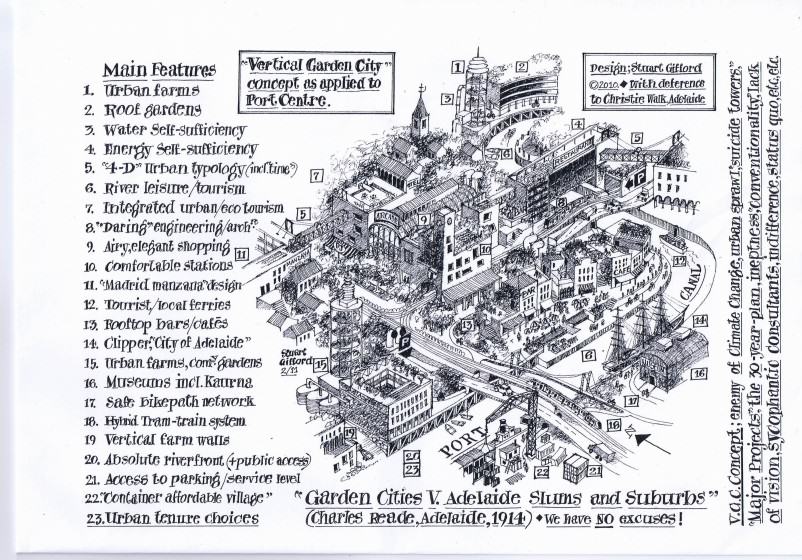

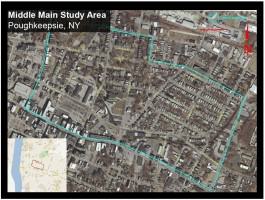

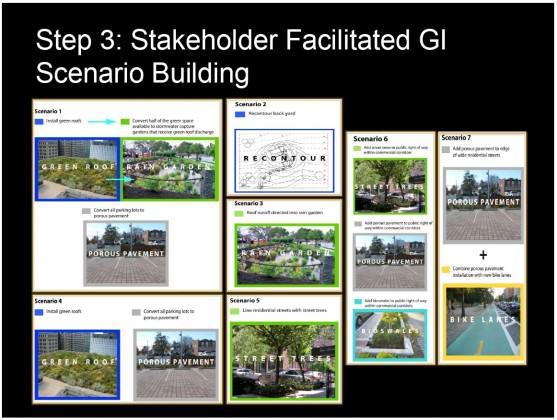

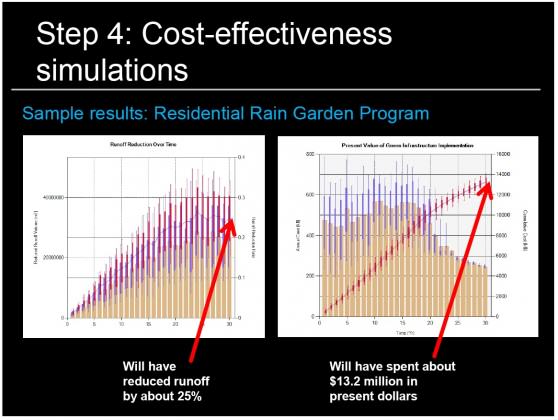

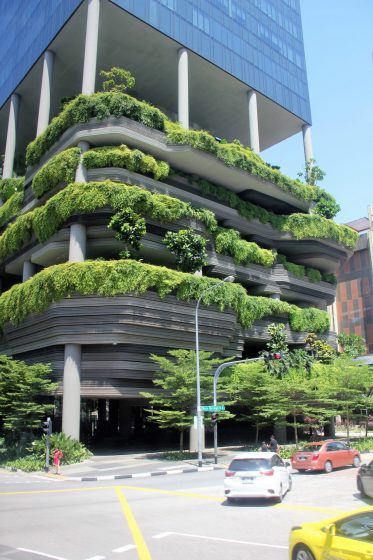

I am very excited about engagement exercises that use simulation models as tools to get people talking not just about their opinions, but about the consequences of their opinions. Incorporating simulation models explicitly into community dialogues is an approach to this. That is, individuals or groups can sit down with a computer simulator of, say, how green infrastructure performs in storm water capture. The people can arrange green roofs, or parks, or street trees on the landscape and the model calculates for them how much storm water has been captured using their design. The science and expert knowledge are built into the inner workings of the simulator (the “black box”). Individuals can try out their designs and social ideas using the model as context, and have the model give some feedback about the how their ideas would work on the ground. Their ideas are taken out of the realm of unverified opinion and placed in a context in which their function, output, and outcomes can be compared. You might still prefer one type of design to another, but its performance could now be part of the decision mix.

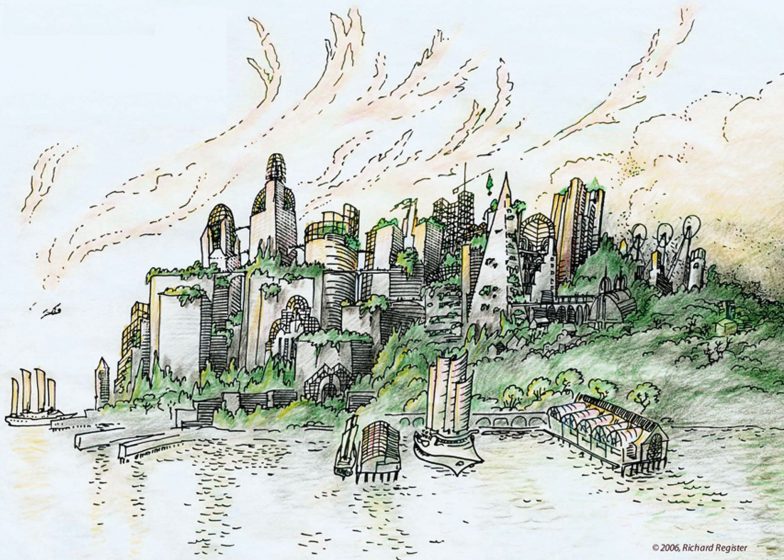

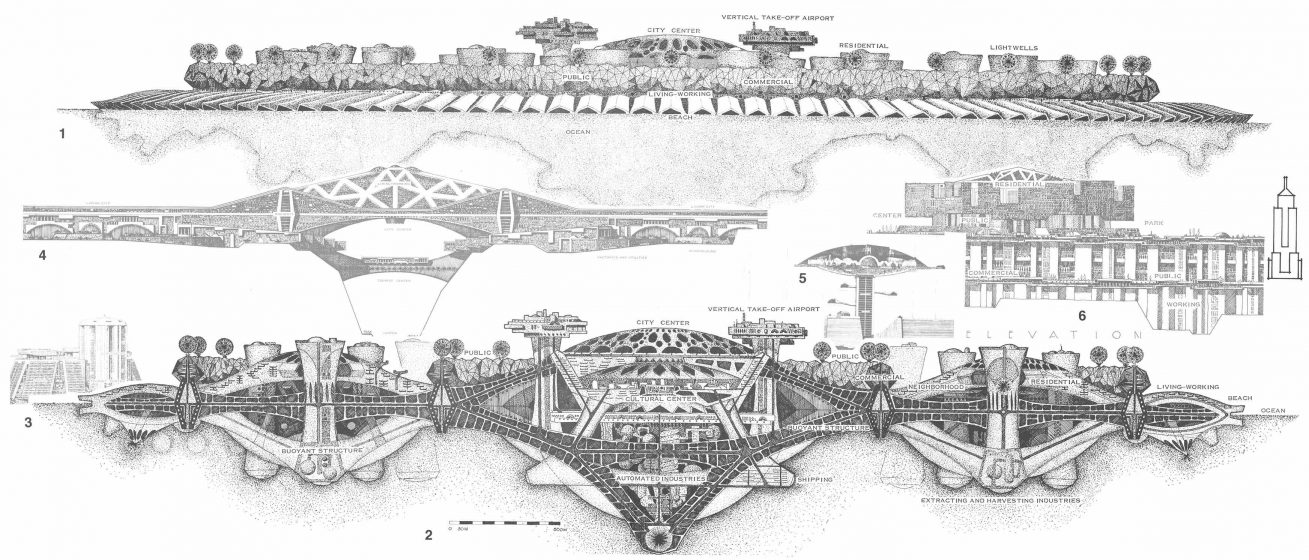

I am very excited about engagement exercises that use simulation models as tools to get people talking not just about their opinions, but about the consequences of their opinions. Incorporating simulation models explicitly into community dialogues is an approach to this. That is, individuals or groups can sit down with a computer simulator of, say, how green infrastructure performs in storm water capture. The people can arrange green roofs, or parks, or street trees on the landscape and the model calculates for them how much storm water has been captured using their design. The science and expert knowledge are built into the inner workings of the simulator (the “black box”). Individuals can try out their designs and social ideas using the model as context, and have the model give some feedback about the how their ideas would work on the ground. Their ideas are taken out of the realm of unverified opinion and placed in a context in which their function, output, and outcomes can be compared. You might still prefer one type of design to another, but its performance could now be part of the decision mix. You redesign Manhattan, block by block, to your specifications and then the “black box” of the simulator calculates a variety of key sustainability statistics, such as energy use, carbon, water flow, biodiversity, human population size, etc. You can register at the website and make your own designs (or “Visions”) or just check out others (there is a library of them). Warning: there is a bit of a learning curve, but investing some time, with patience, is fascinating and greatly rewarding. The creators have plans to continue improving it, including things like learning “competitions” to find to best and most productive design ideas.

You redesign Manhattan, block by block, to your specifications and then the “black box” of the simulator calculates a variety of key sustainability statistics, such as energy use, carbon, water flow, biodiversity, human population size, etc. You can register at the website and make your own designs (or “Visions”) or just check out others (there is a library of them). Warning: there is a bit of a learning curve, but investing some time, with patience, is fascinating and greatly rewarding. The creators have plans to continue improving it, including things like learning “competitions” to find to best and most productive design ideas. Does one person in your area want to invest everything in green roofs, while another thinks street trees are the answer? The model can help place the consequences of these alternatives in context (at least from a storm water perspective), making their relative outcomes easier to see, digest, and decide upon. Sure, there would still be decisions to make that are outside the scope of Lidra — aesthetics, access, equitability, and so on — but the model helps take at least some of the guesswork out of the process.

Does one person in your area want to invest everything in green roofs, while another thinks street trees are the answer? The model can help place the consequences of these alternatives in context (at least from a storm water perspective), making their relative outcomes easier to see, digest, and decide upon. Sure, there would still be decisions to make that are outside the scope of Lidra — aesthetics, access, equitability, and so on — but the model helps take at least some of the guesswork out of the process.

All models are wrong — some are useful

All models are wrong — some are useful

3 Comments

Join our conversation