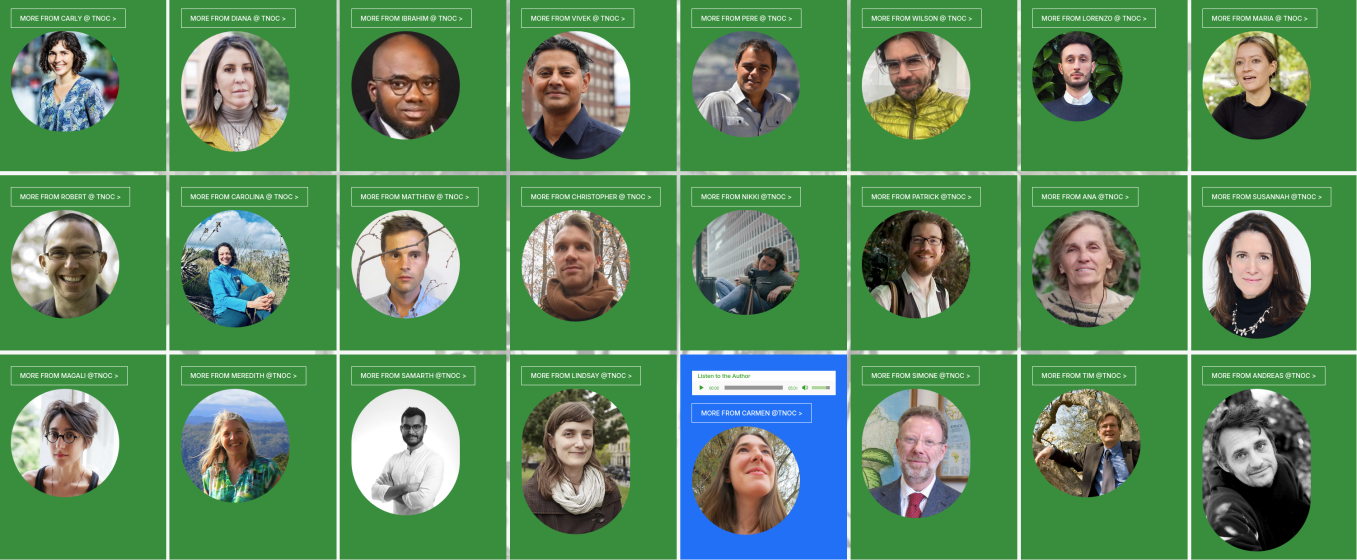

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

This is an invitation to humility and courage at once: to act without guarantees, to plant trees whose shade we may never sit under, to repair what we can, to refuse what harms, to contribute to an uncertain future, and more than anything, to build lasting relationships.

Humility and courage

What does it mean to be a good ancestor to the people, places, or more-than-human lives we care about? This question turns “ancestor” from a family label into an ethical stance: not just who we come from, but who we are willing to become for those who will come after us. It asks us to pause and feel the long arc of responsibility—across generations, across species, across landscapes—and to notice that ancestry is not only about blood or chronology, but about relationship, influence, and inheritance. To be an ancestor is to leave traces. Some are visible—policies we shape, habitats we restore, stories we tell, institutions we build. Others are quieter—habits we model, kindnesses we ripple outward, ways of paying attention that help a place or a community endure.

And then there is “care,” which is never as simple as affection or good intentions. Care is a verb and a practice. It’s the daily work of tending, listening, staying with complexity, and making choices that protect possibility rather than narrow it. Care is also a willingness to be changed by what we care for—to let a river, a neighborhood, a child, a forest, a peer, a bird population, or a future stranger have a say in how we live now. So this prompt invites us to hold both meanings together: ancestor as a commitment to futures beyond our sight, and care as the craft of acting with tenderness and accountability in the present.

What’s beautiful about the prompt is that it doesn’t demand a single mode of answer. It welcomes the intuitive and the practical, the speculative and the grounded. Some might respond with a plan, a promise, a question, a poem, a small habit you want to nurture, or a risk you feel called to take. It’s less an exam than a doorway: a way to gesture toward futures we cannot fully imagine, and to ask what we do anyway—knowing everything is uncertain, knowing we won’t be here to see how the story turns out. In that sense, it’s an invitation to humility and courage at once: to act without guarantees, to plant trees whose shade we may never sit under, to repair what we can, to refuse what harms, and to widen the range of what might be possible for others—human and more-than-human—later on.

What’s beautiful about the prompt is that it doesn’t demand a single mode of answer. It welcomes the intuitive and the practical, the speculative and the grounded. Some might respond with a plan, a promise, a question, a poem, a small habit you want to nurture, or a risk you feel called to take. It’s less an exam than a doorway: a way to gesture toward futures we cannot fully imagine, and to ask what we do anyway—knowing everything is uncertain, knowing we won’t be here to see how the story turns out. In that sense, it’s an invitation to humility and courage at once: to act without guarantees, to plant trees whose shade we may never sit under, to repair what we can, to refuse what harms, and to widen the range of what might be possible for others—human and more-than-human—later on.

If I had could see four threads in these diverse responses, they would be these:

- Good ancestorhood is about how we care now, not how we’re remembered. Rather than controlling legacy, contributors emphasize acting with care, humility, and generosity in the present, accepting uncertainty about the future.

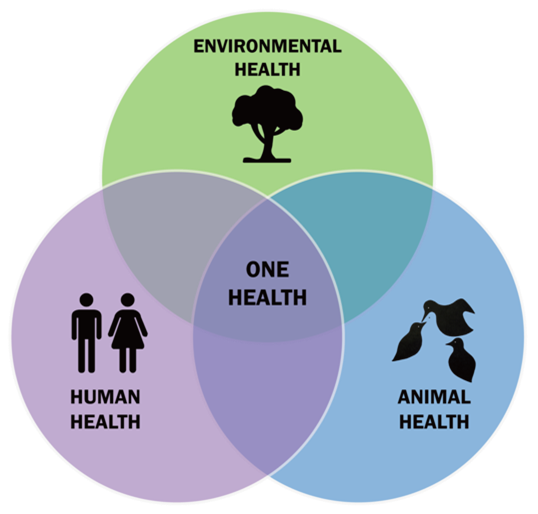

- Ancestry is relational, extending beyond family to place and the more-than-human world. Being a good ancestor means caring for shared landscapes, cities, communities, and ecosystems, recognizing multispecies interdependence.

- Legacy is measured in relationships, not achievements. What endures are people, connections, teachings, and the ongoing practice of love—not publications, titles, or institutions.

- Long-term responsibility is difficult, but must be practiced together. Despite the challenge of thinking beyond our own lifetimes, contributors stress collective action, reciprocity, and belonging as the seeds of hope for future generations.

This roundtable lands for me as more than a lovely reflection. It feels like a compass for the relationships we nurture, the work we choose to do, and the way we choose to do it. It reminds me that scholarship, planning, activism, art, teaching, care work, community-building, parenting—all of it—can be understood as an ancestral practice. Each choice is a kind of message to the future: this is what we valued, this is how we behaved when we knew what we knew, this is how we treated the world that held us. The prompt nudges us to ask, again and again, not only “what are we building?” but “what are we passing on?” and “who will live and perhaps hopefully thrive with the consequences?”

And maybe, most quietly, it asks whether we are living today in a way that future beings—people we’ll never meet, species we can’t name yet, organizations we build, places that will outlast us—might recognize as love.

The banner photograph is by Mike Houck.

about the writer

Toni Luna

Toni Luna has taught geography at Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF) since 1996. He has served several positions at UPF: Academic Coordinator of Interantional Programs, HEad of the Humanities Department, Academic Coordinator of the Global Studies Degree, and Vicerector of International Relations. His recent projects engage with geohumanities, hydrosocial territoriality, and creative approaches to understanding landscapes and communities.

Toni Luna

Ancestry in the Classroom: Lessons Passed Down, Lives Passed Forward

In the end, our legacy isn’t measured in publications or committees—it’s measured in people.

When people talk about “being a good ancestor”, they often imagine grand, impressive acts such as building libraries, planting forests, or writing a novel. But in teaching, ancestry happens in much smaller, quieter, and sometimes chaotic moments. It happens in the classroom at unreasonable hours, in tutoring sessions in the teachers’ offices, or online, or in the school cafeteria, or also on field trips when students discover that Geneva diplomacy is less glamorous than expected, or in Tangier when they realise borders are lived, not drawn.

For me, the idea of being a good ancestor starts with remembering the people who shaped me. Recently, I lost one of my closest academic mentors, someone who guided me with a mixture of wisdom, affection, and the occasional necessary push. I still remember asking her, years ago, whether having children was a terrible idea for my academic future. She didn’t hesitate: “Kids and family are first. Careers can wait.” That advice—simple, human, and profoundly grounding—became one of the ancestral threads I carry with me.

Then there was the senior colleague who taught me what crafting a class actually means. From pacing a lecture to treating students with respect, he showed me how teaching is an art form, not just a workload. Only much later did I realise how much of my approach, my insistence on clarity, care, and humor comes directly from those early days under his wing.

And now, wonderfully, I’m learning from younger colleagues who keep bringing in new ideas, new tools, new topics, and new ways of connecting with students. They remind me that ancestry isn’t something that flows only from old to young. It circulates. It adapts. It surprises you when you least expect it.

But ancestry is not only about those who shaped us. It’s also about the lives we touch along the way, sometimes without even realising it.

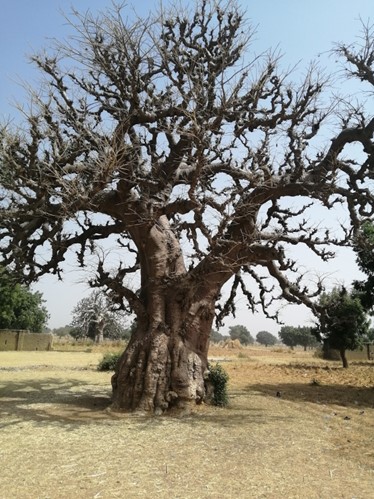

A few years ago, a couple came to see me at the university. They arrived with a Gambian mother and her son, Mamadou, who wanted to study Global Studies. At the time, I was the academic coordinator, and thanks to the heroic efforts of an administrative colleague, one of those angels who carry the university on their shoulders, we managed to make it happen. Mamadou came from a very poor background; his mother worked as a janitor, and he commuted long hours every day because he couldn’t afford to live in Barcelona.

Years later, the day he graduated, his whole family appeared dressed in the vibrant colors of West African celebration. I still remember the emotion of seeing them together, joyful, proud, radiant, and I could barely speak. I told them that moments like this are what make our work meaningful: when you see a life transformed, across languages, cultures, religions, continents. That’s when you understand that teaching is never just teaching.

Not long ago, Mamadou married, and he sent me a message I will never forget:

“Your presence alone is enough to inspire. Back then I thought I was the only one who always went to you when something needed solving. Then I realized everyone else was the same! People would say, ‘Did you speak with Toni? He’ll figure something out.’ May you keep inspiring us!”

Because being a good ancestor in teaching doesn’t require brilliance or perfection. What it requires is presence. Listening. Guiding. Taking students seriously. Sharing our own doubts and learning from theirs. Passing forward the care that others once gave us.

In the end, our legacy isn’t measured in publications or committees—it’s measured in people. In the students who carry a small piece of our influence into futures we will never see. In the stories that continue long after our course has ended.

And if that’s what ancestry is, then I’m grateful to be part of it.

about the writer

Camila Sant'Anna

PhD in Architecture and Urbanism from the University of Brasília, with a thesis entitled: Green infrastructure and its contribution to the design of the city’s landscape (2020). Sandwich PhD at the University of Manchester, funded by CNPq (2019). Master’s degree in Theories and Approaches to Landscape Design from the École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Versailles, ENSPV, France (2009). Master In Human Geography from the Université Paris Diderot. Professor at the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of Brasília (UnB). She is interested in the topics climate change, landscape planning and design, green infrastructure, SbN, and Popular Knowledge.

Camila Sant’Anna

A Good Ancestor in the Southwards

Solutions need to be co-created that engage with the bioclimatic regions of the South, capable of generating income and empowering their population.

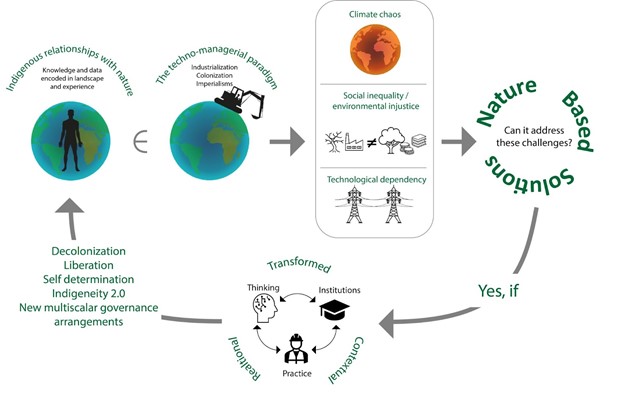

Being a good ancestor is to act, reviewing the paradigm of understanding landscape and its relationship with the environment, from the perspective of the South, valuing the nature of its margins and its worldviews. Marginal landscapes are home to vulnerable communities, most of whom lack access to environmental and sociocultural benefits due to issues of race, income, nationality, and gender. Rethinking the role of marginal landscapes in an integrated way means listening to the voice of these communities, valuing their traditional knowledge and their relationship with nature.

Understanding landscape as a necessity and an infrastructure. This is a crucial condition for guaranteeing a landscape that is a right for all and for the ancestral present and future (KRENAK, 2020) to become a reality.

Therefore, it is necessary to understand how to valorize and build landscapes as the infrastructure that will guide sustainable development and adapt to climate change in a territory with so many socio-environmental challenges, such as that of the Global South and, at the same time, holding a large portion of biodiversity hotspots, fundamental for the survival of the Earth.

The construction of an anti-racist, anti-gender urban climate adaptation that addresses social inequality and is inclusive involves consolidating a landscape experience based on Southern perspectives, capable of addressing environmental racism and promoting environmental and climate justice (IPCC, 2023), addressing the vulnerable situation of its largely invisible population, mostly female and Black. To be a good ancestor is necessary to “relearn to hope” as an act of care.

Currently, some multi-scalar proposals involving landscape and environment in the face of contemporary challenges translate into top-down strategies for the renaturalization of cities, based on different proposals, nature-based solutions, green infrastructure, and ecosystem-based adaptations. We have the example of those born and developed in the Global North, generally aiming to promote high-performance ecological green and blue systems capable of restoring and enhancing ecosystem services and promoting the ecological cycle of cities. However, these solutions often translate into punctual interventions and are implemented in areas with higher purchasing power. Solutions need to be co-created that engage with the bioclimatic regions of the South, capable of generating income and empowering their population. They need to promote not only ecological resilience but also build [re] existence.

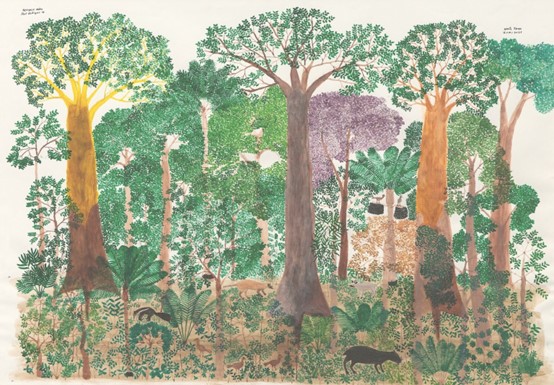

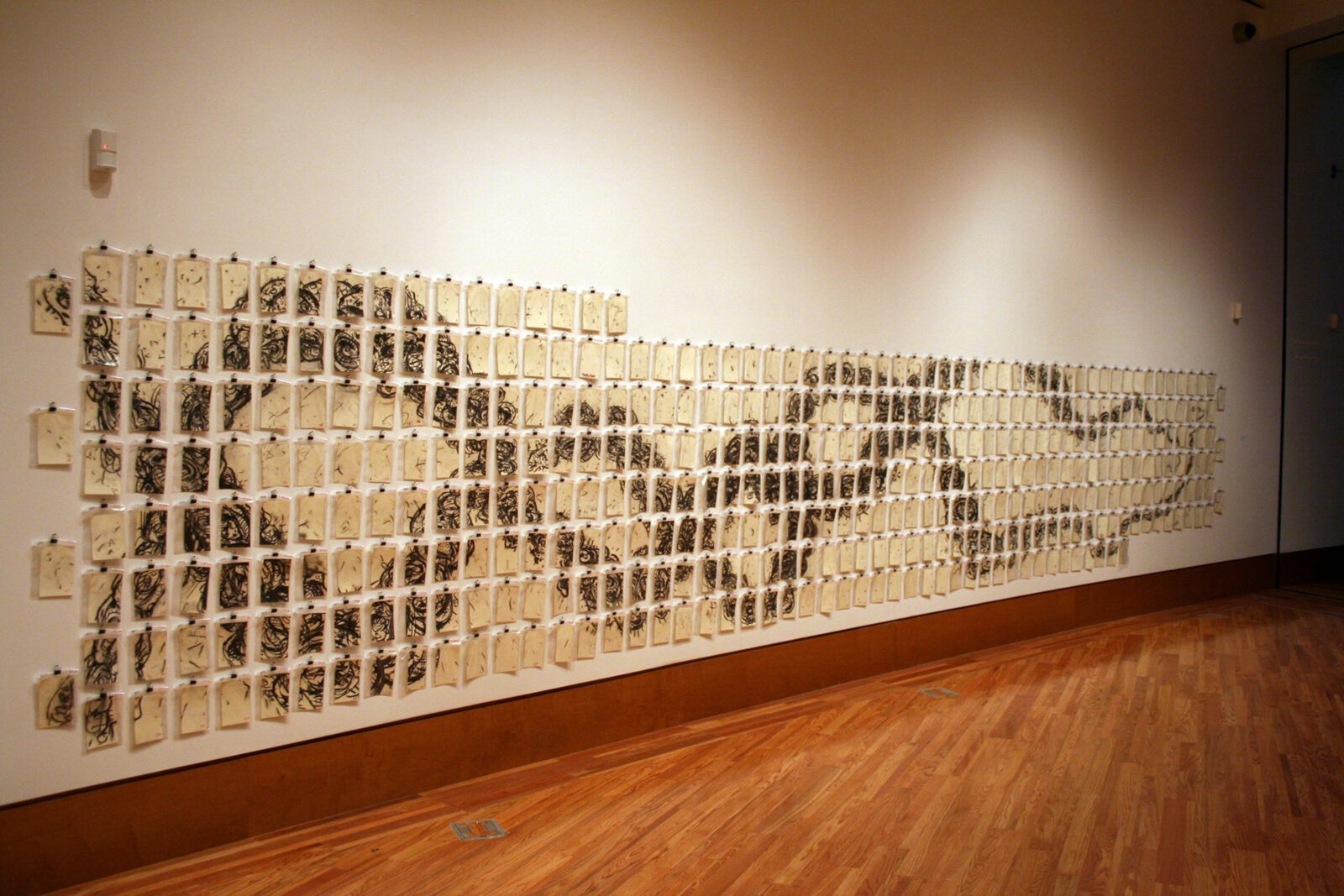

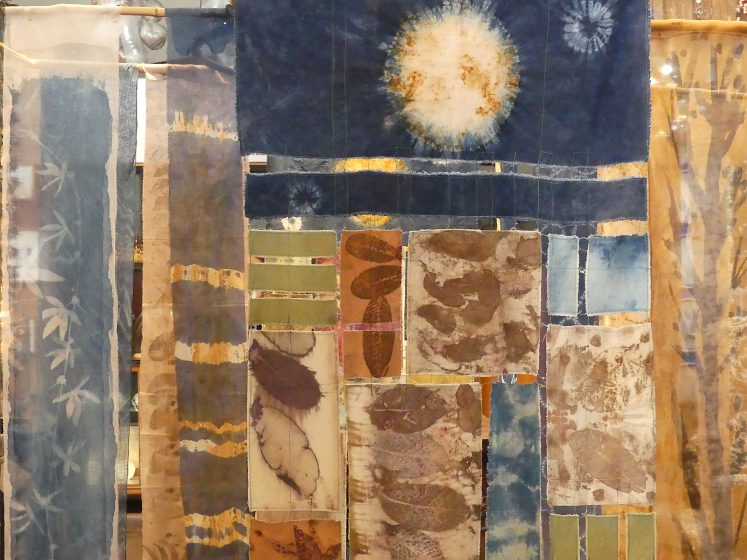

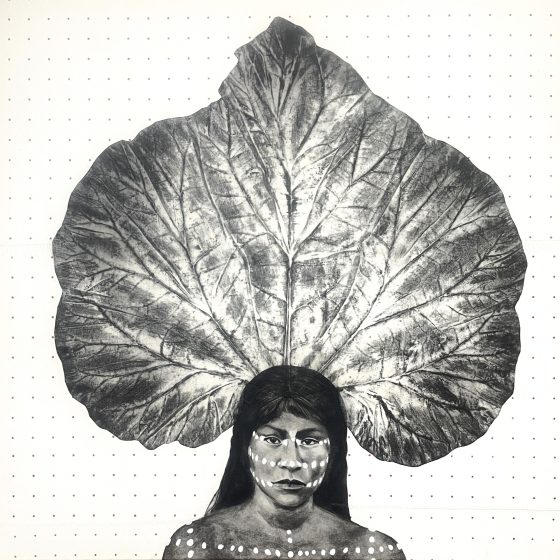

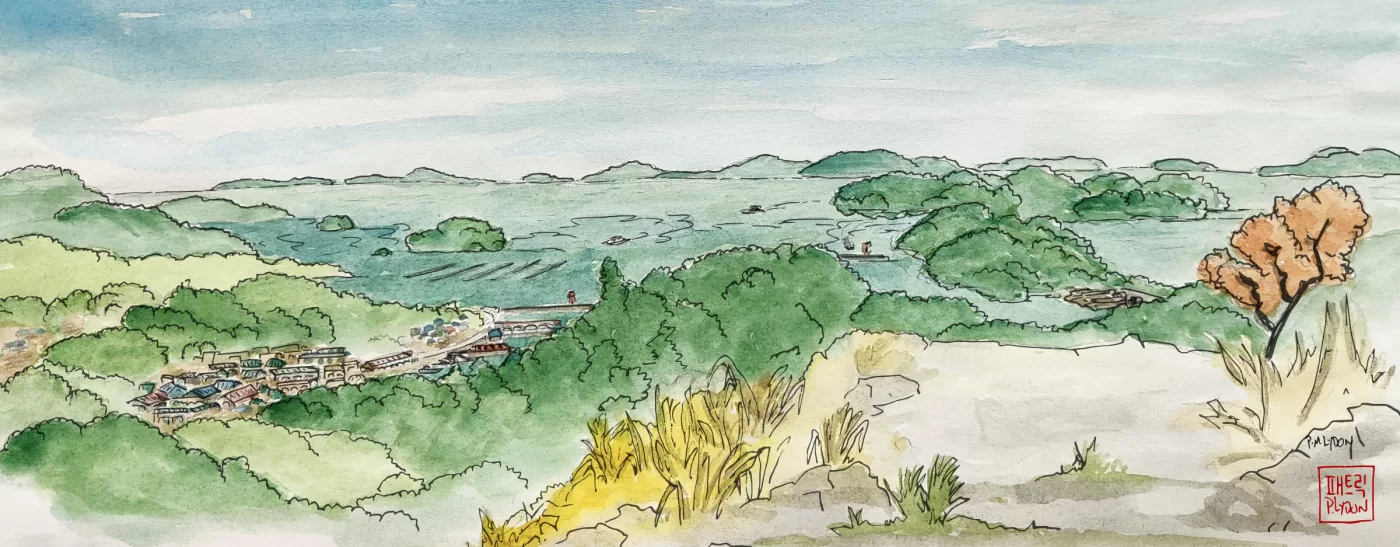

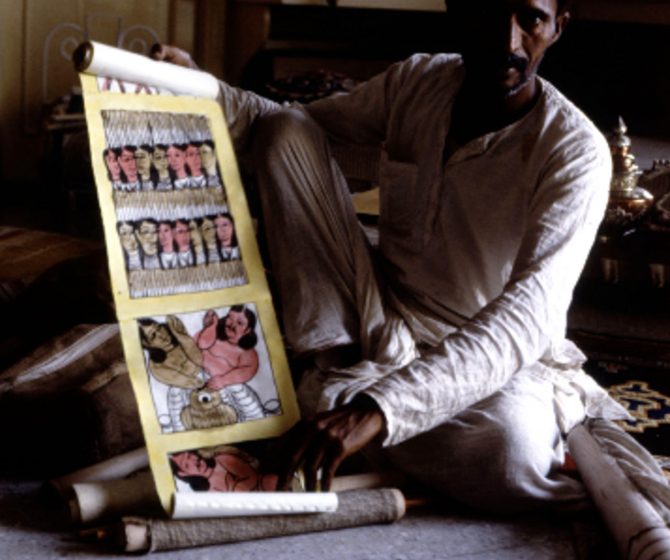

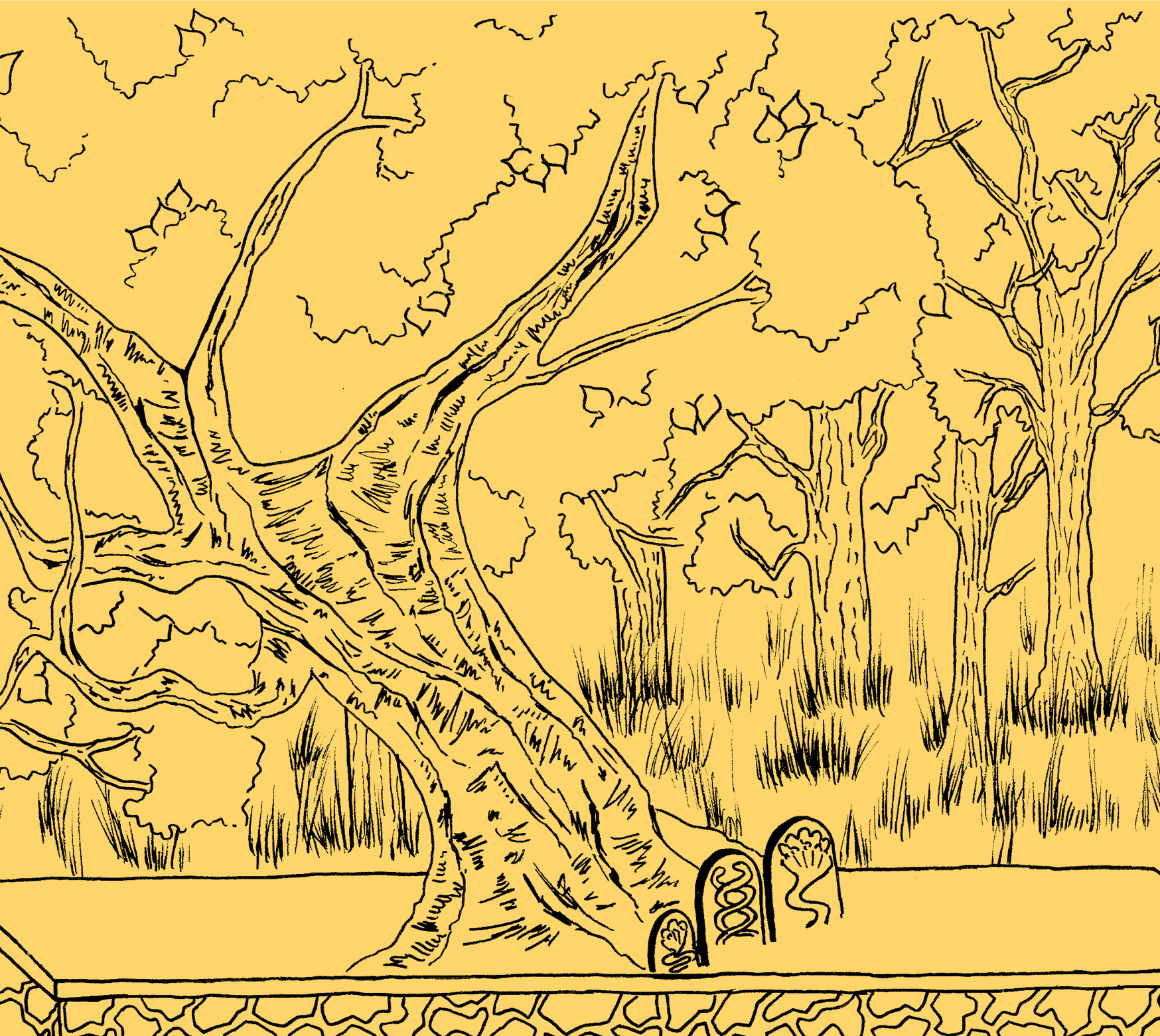

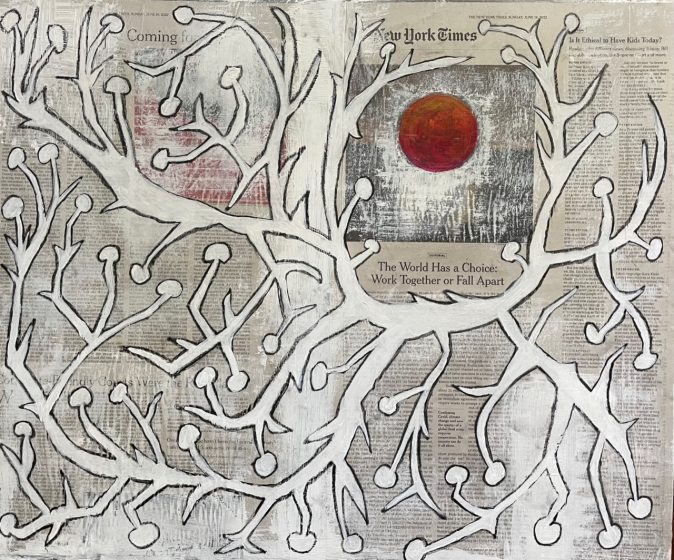

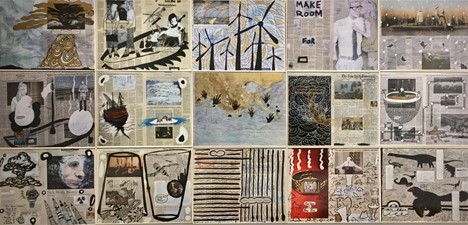

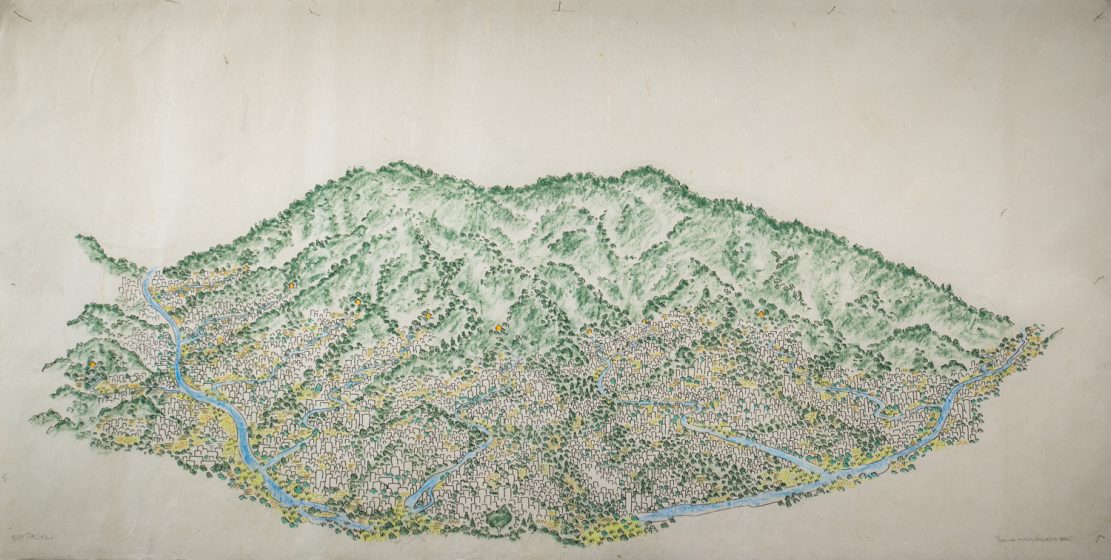

Below are attached two images of [re]existence. They are from the workshop “Redesigning Ancestral Landscapes between the Sea and the Land of Salvador” that aimed to rethink the design of two areas in Gamboa (Salvador, Brazil) and promote participatory painting and planting action in these areas. The Organization of a Community Urban Landscape Design workshop was in dialogue with the discipline Landscape Foundations Workshop (ARQC13), taught by Ana Caminha, Camila Gomes Sant’Anna, and Marta Alves, and the discipline ARQD53―Mutual Construction Practices, taught by Professor Marcus Vinicius Augustus Fernandes Rocha Bernardo of the Faculty of Architecture at Federal University of Bahia (FAUFBA).

The proposal has Ana Caminha as a visiting resident at FAUFBA. She is president of the Association of Friends of Gegê of the Residents of Gamboa de Baixo (Associação Amigos de Gegê Dos Moradores da Gamboa de Baixo), coordinator of the Gamboa Women’s Group, and, since 2014, one of the coordinators of the Articulation of Movements and Communities of the Old Center of Salvador. She was an important agent in the mobilization of the community.

The proposal has Ana Caminha as a visiting resident at FAUFBA. She is president of the Association of Friends of Gegê of the Residents of Gamboa de Baixo (Associação Amigos de Gegê Dos Moradores da Gamboa de Baixo), coordinator of the Gamboa Women’s Group, and, since 2014, one of the coordinators of the Articulation of Movements and Communities of the Old Center of Salvador. She was an important agent in the mobilization of the community.

about the writer

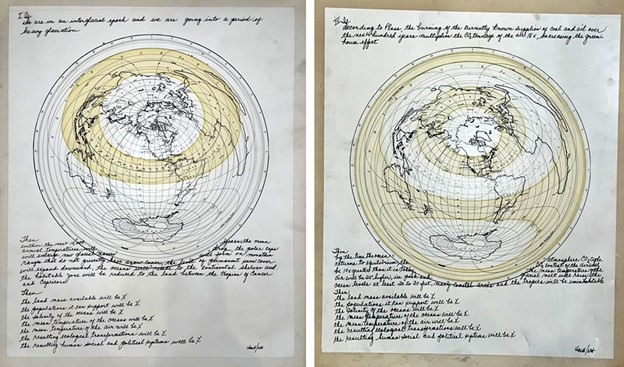

David Haley

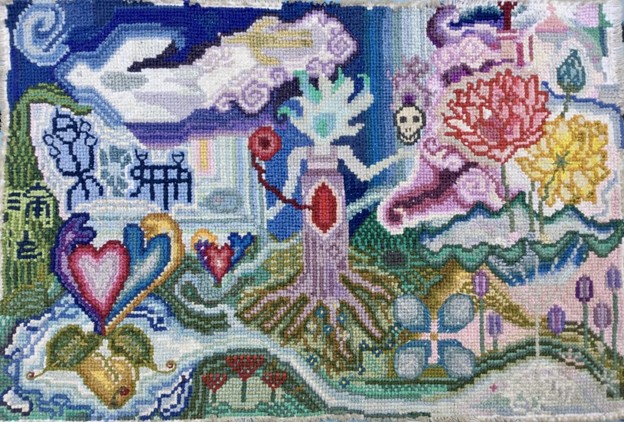

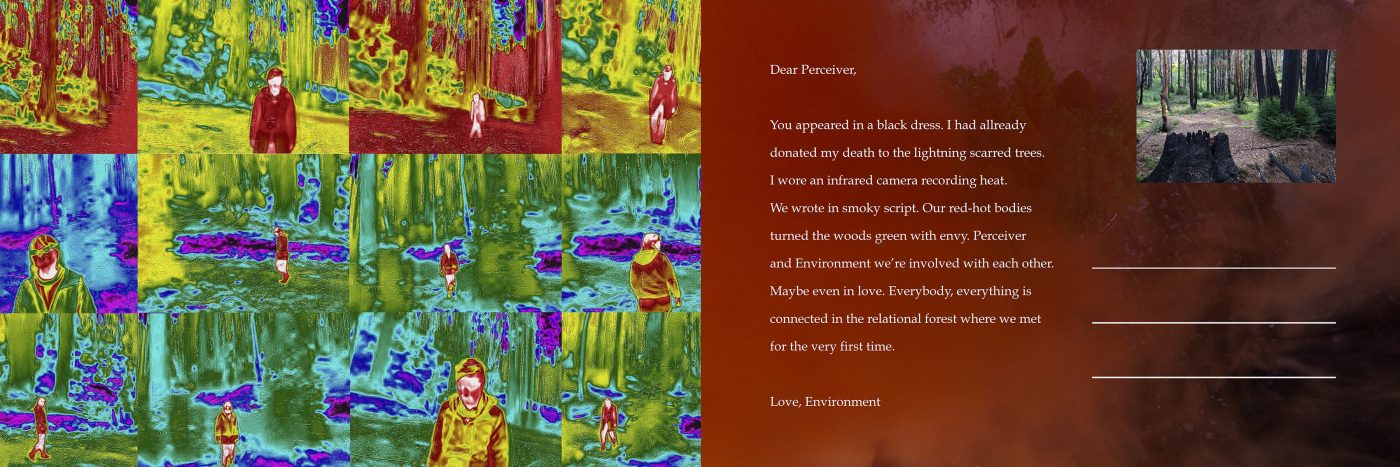

David makes art with ecology, to inquire and learn. He researches, publishes, and works internationally with ecosystems and their inhabitants, using images, poetic texts, walking, sculptural and video installations to generate dialogues that question climate change, species extinction, urban development, the nature of water transdisciplinarity and ecopedagogy for ‘capable futures’.

David Haley

Be Good In The Now

We can only be “good” in the now and trust in our art.

In 1992, when I found out about “climate change” and read the Rio Earth Summit book[1], I formed three questions:

- How can I and those I love survive the impacts of climate change?

- Who are those I love?

- How can I, as an artist, address climate change?

Biodiversity loss as a greater concern, exacerbated by climate change, became quickly evident. Then, given the indeterminacy of evolution and Charles Darwin’s primary strategy of adaptation (not competition)[2], I considered “culture” to be the missing factor from the dominant climate and species extinction narratives that focused on science, politics, and economics. As a creative cultural connector, the arts potentially offered other disciplines and societal sectors the ability to think differently about how we live. This provided my way into studying these profound issues that would impact my daughter, then aged 4. Gregory Bateson’s “ecology” provided “the pattern that connects”[3] and deeper understandings of ecology that included time as a determining factor came from Arene Naes[4] and Lynn Margulis[5].

Since then, I have endeavoured to learn how to be an ecological artist, making art with ecology. Serendipitously, I worked with the pioneers of ecological arts, Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison[6], gaining insights into the process of Socratic Dialogue―forming questions that enable others to learn for themselves. Basarab Nicolescu’s development of “Transdisciplinary Knowledge”[7] provided further potential for thinking and acting “between, across and beyond all disciplines”. Serendipity and hard work also gave me the opportunity to lead a Master’s course in “Art As Environment” (2003-2012) and develop the cross-faculty research initiative, “Ecology In Practice” (2010-2016). I was and still am fortunate to work with amazing students and some colleagues. Such “eco-pedagogy” continues to form the basis of my practice as an artist-researcher-educator and being. But I realised that Academia was becoming industrialised, to the point where questioning the system (impiety) was perilous, as did Socrates. Luckily, I found solace in Paulo Freire, whose revolutionary pedagogy continues to inspire those souls brave enough to challenge the dogma of unimaginative autocracy[8].

Latterly, on observing seagulls teach their fledglings how to fly, find food, and know what danger looks like, I realised that every sentient being’s culture is based on intergenerational co-learning for the survival of their species. Perhaps, this is what it means to be a good ancestor to the things or people we care about?

However, beyond my immediate family and circle of friends, who do I love; who and what do I really care about? This question, I have not yet resolved. I may feel compassion for others, but I cannot honestly empathise with those I do not directly know or engage with. Vanessa Andreotti (aka Machado de Oliveria), in her considerations of the “Nature-Climate-Culture Emergency”, seeks to learn with “others” how things may be “otherwise”[9]; so perhaps this cultural co-learning is a kind of love, across, between, and beyond our immediate kin and community?

However, regarding our potential ancestral legacy, like George Orwell, I am aware that, “Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past”[10]. As we see histories re-written or erased by dominant cultures, influencers, and AI, who knows what our descendants will think of us? We can only be “good” in the now and trust in our art (Rta) “The dynamic process by which the whole cosmos continues to be created, virtuously”[11].

[1] United Nations (1992) Earth Summit ’92: The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. Rio de Janeiro 1992

[2] Darwin, Charles / Leakey, Richard (1986) The Origin of Species. Faber and Faber, London

[3] Bateson, Gregory (2000). Steps to an ecology of mind. University of Chi-

cago Press, Chicago. P 512

[4] Naess, Arne. ‘The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movement: A Summary’, in Drengson, Alan Inoue, Yuichi eds. The Deep Ecology Movement: An Introductory Anthology (Berkely California: North Atlantic Books, 1995).

[5] Margulis, Lynn. The Symbiotic Planet: A New look at Evolution (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1998).

[6] Mayer Harrison, Helen and Harrison, Newton – https://www.theharrisonstudio.net/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Harrison_Studio

[7] Nicolescu, Basarab (2008) Transdisciplinarity: Theory and Practice. Hampton Press Inc., New Jersey

[8] Freire, Paulo (2017). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Penguin Modern Classics, UK

[9] Andreotti, Vanessa “Global citizenship education otherwise: pedagogical and theoretical insights”. In Ali Abdi, Lynette Shultz, and Tashika Pillay (Eds.) Decolonizing Global Citizenship Education. (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2015). pp. 221-230

[10] Orwell, George (2000) Nineteen Eighty Four. Penguin Modern Classics. London

[11] Robert Pirsig (1993) Lila: An Inquiry Into Morals. Black Swan, London p.407

about the writer

Kate McGloughlin

Kate McGloughlin is a celebrated painter, printmaker and instructor at the center of the art colony of Woodstock—The Woodstock School of Art, and has been leading creatives on painting excursions around the globe since 1998. Spiriting an ethos of curiosity, goodwill, and inclusion, McGloughlin infuses multimedia art adventures with warmth and a heart for kindling transformation through engaging work and play experiences for participants and the ecosystems in which they find themselves.

Kate McGloughlin

The People of Davis Corners

May the work you continue to uncover be as practical in implementation as it is marvelous in its ethos.

We live in the house my grandfather and two of his best friends built in 1922, at Davis Corners, in Olivebridge, New York. The land it sits on was granted to my ancestor, Kit Davis, in a 17th-century land patent on the unceded land of the LENI LENAPE. My people have lived, loved, married, given birth, farmed, and died here for twelve generations. In turn, I have been painting the fields, brooks, and wood lots that they worked since I was thirteen. Their work sustained their families; my work has sustained mine.

In the summer months, I mow the lawn weekly and almost always think of my grandfather, who mowed this patch until my twin brother and I were tall enough to reach the clutch on the Montgomery Ward Ride on Tractor. Every new dip in the lawn signifies a new tunnel, made by voles, or the presence of a new spring. Alas, water finds its way, and so have I.

I got away from this farm as soon as I could—at eighteen, for college—and came back when I needed to look after my beloved grandmother. I found my way to a local art school where I have been able to do service to my profession as a landscape painter and printmaker, and where I eked out a living, on this- just-under-two-acres and farm house that came with a barn/garage with an apartment built as a honeymoon cottage for my aunt and uncle, just after the war.

The hundreds of other acres that were cared for by Kit’s early descendants were first donated to create a town around the farm—the Methodist Church and parsonage and the Odd Fellows Hall were sectioned off from the early farm—then sold off to other small farmers and those who would become cherished neighbors and friends.

Caring for the land and home is what we do. We don’t feel that we own it, but we do feel like we’ve polished up and improved on what we were handed. Neither my partner Sarah nor I have the stomach to raise animals, (why do they call it livestock? It should be called dead stock, for sure…) nor do we hay the one small field that is ours. We will continue to pay our neighbor to do that until we have more time to tend to what we might grow there. We do carry on Pa’s legacy as we care for a small patch that provides greens and tomatoes, and an enviable herb and tea garden that lures local bees from their hives to our land to make love to.

I wasn’t lucky enough to inherit the barnyard or 1948 Allis Chalmers Tractor, but my cousin lets me prowl around in the Horse Barn that was part of his inheritance, and I did manage to score a lot of cool old rusty farm equipment to have and to hold and cherish forever. I really do know what each part went to, and the memories that a rusty piece of a harrow can conjure rival a bite into any Proustian Madeleine. It’s potent, and I remember them. The studios I built in my time have replaced the milk house and granary, silo and hay mow; each building a nod to the past, with functional spaces, and red siding, with white trim.

Lately, I’ve been creating assemblages using wood from the remnants of our barn and bolts and nuts and washers and bits of harnesses and bridles, windows, and doors. Each assemblage, steeped in heritage, now holds things that at least 5 generations of my ancestors held in their hands, and though there will be no generations going forward of my own, my cousins’ kids will have something from my hands, too. And my heart, I suppose.

Of course, this is only one set of ancestors that I’ve remembered and to whom I’ve tended. In my last four major exhibitions, called “Requiem for Ashokan”, I remembered another side, each show a different iteration of work showcasing the devastation of my generational community and our homesteads that were razed during the creation of the Ashokan Reservoir. I wanted their stories and sacrifices remembered, so I put it in writing, and on the walls of two museums, two other gallery spaces, and in the frames of a small documentary film.

I have loved my people more after each telling, and I have been so honored to be asked to contribute this piece for this cohort, as well. May the work you continue to uncover be as practical in implementation as it is marvelous in its ethos.

Requiem for Ashokan:

https://www.katemcgloughlin.com/video

about the writer

Morgan Grove

Morgan Grove is a social scientist and Lecturer at the Yale School of the Environment. He is a Co-Chair of Baltimore City’s Sustainability Commission and Team Member of the Baltimore Ecosystem Study (BES). Morgan worked for 30 years for the USDA Forest Service, where he was the Team Leader for the Baltimore Field Station.

about the writer

Steward Pickett

Steward Pickett is a Distinguished Senior Scientist Emeritus at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York. His research focuses on the ecological structure of urban areas and the temporal dynamics of vegetation.

Morgan Grove & Steward Pickett

On Being a Good Ancestor

Each of us must accept our place in the stream of ancestors. Remember, you didn’t get where you are on your own.

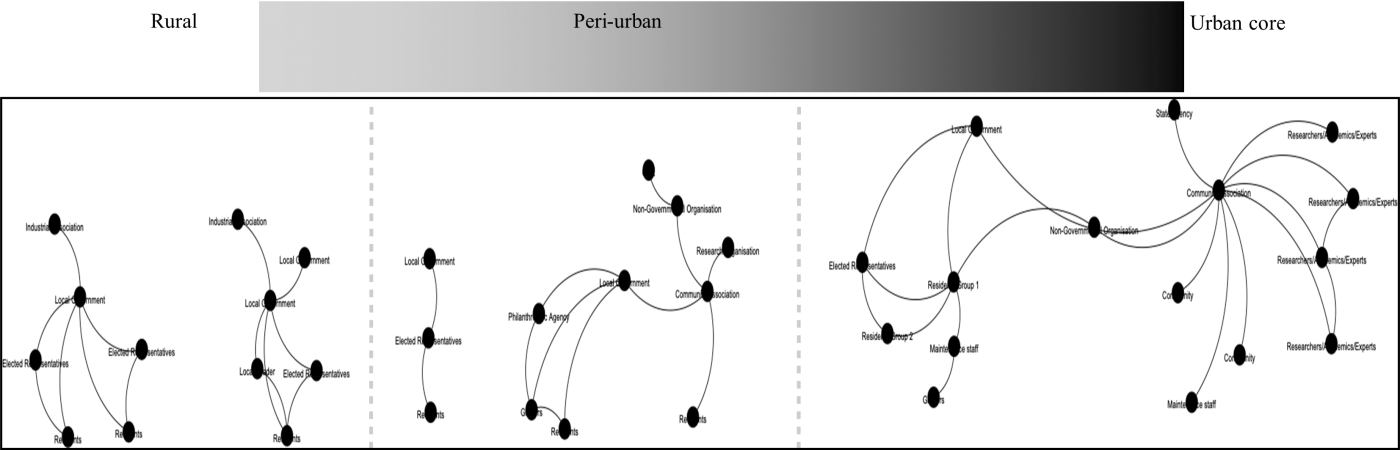

Ancestry is a broad and powerful idea. We find it to be more like a network or a village than the usual concept of “lineage” embedded in a mythological American middle-class nuclear family―Mom, Dad, two kids, and a dog. But this highly situated myth neglects the nearness of half-siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and even neighbors in many cultures. If it “takes a village to raise a child,” so too are networks the shape of ancestry. As researchers and leaders of projects intended to advance social-ecological urban science and its practice in the real world, we are naturally concerned with the nature of academic and practical ancestry.

When we speak of ancestry, it might be a better idea to use a term that does not imply simply genetic or narrow hereditary relationships. Maybe we should speak of “ancestorhood,” because that is a mantle of responsibility that can be chosen, learned, enhanced, and passed on. This broader framing is why we consider how to become a good ancestor. Ancestorhood is a familiar concept in some Indigenous, African, and Asian cultures.

First of all, ancestorhood is a chosen or accepted relationship that builds on the generations before but grows into the future. The present network is temporary, but that means we can always be doing better for those yet to be a part of the community of urban ecology. While having literal children cannot be a requirement of academic and practical ancestorhood, nurturing intellectual and practitioner descendants is certainly required. The first principle of ancestry in science and practice is that each of us has ancestors and will be an ancestor.

What kind of ancestor will we be? Because scientific and practice ancestorhood is a relationship of responsibility, it raises a familiar question: “What does the work of our ancestors require of us?” One thing the current generation needs to do is to acknowledge that ancestral work. What has come down to us, in terms of materials, skills, ideas, values―in a word, culture―of our science and practice?

The honoring of ancestors and the desire to become better ancestors is really the “lifting up” of community and networks, not only in the present, but across time. We have learned from ancestors living and dead, as well as those younger than ourselves and older. Based on what we have learned from these people, here are some things we believe might help us and others be better ancestors. These are ethically motivated statements.

Each of us must accept our place in the stream of ancestors. Remember, you didn’t get where you are on your own.

Accept your responsibility in the community of ancestors. Consider how you can help somebody else be a part of the social-ecological community and its contribution to the larger world. Welcome newcomers to the community.

Kindness is a core value of ancestorhood, even when critical advice is offered.

Remember that students and newcomers to the field, especially those from groups that are not numerically large in the field, may require particularly thoughtful nurturing.

Ancestry can be direct or indirect. By definition, we cannot personally know all our potential ancestors. Look for positive multiplier actions. One indication of success is the phrase, “I’ve heard so much about you”.

Do not propagate or tolerate ill treatment, such as hazing. If you were hazed, that is regrettable and shouldn’t have happened. Don’t pass it on.

Members of all generations and ages should be included and honored. This is similar to two of the requirements of environmental justice: ensure inclusive participation and recognize all voices and perspectives in dialogue.

Include students and young faculty or agency staff in positions of responsibility. Give them chances to participate meaningfully in leadership, such as steering committees, project management, and group blue sky thinking.

Share opportunities to write papers that go beyond technical graduate training, especially syntheses, explorations of new methodologies, new ideas, and new study places. Participation in grant writing, whether to science agencies or private foundations, is a valuable shared experience. Such activities can expand the experiences of all generations.

Conduct activities that include people of all ages, interests, and backgrounds. Events like field trips to places few in the group are familiar with are especially useful in promoting inclusion and growth.

Be attentive to where people are in their life paths and make opportunities available that will help facilitate their advancement, while at the same time avoiding failure-prone situations.

The “old heads” sometimes have to choose to be quiet and let hopeful descendants speak and lead.

Build formal and informal institutions that favor multigenerational ancestorhood. We hope that the evolving Baltimore Ecosystem Study exemplifies conscious sowing of seeds of ancestorhood that have been planted and tended by many different people over the nearly 30 years of that project.

What is the best image or metaphor for ancestorhood? Ancestry and lineages of heritance are often spoken of as trees. A family tree is a common image. But that is really quite static, and it emphasizes a small reproductive unit. The philosophy we laid out at the beginning of this essay is about something much broader, more inclusive, and open to new intellectual and practical relationships. Perhaps we should speak of a braided stream of community. But the stream we envision is not the inevitable outcome of gravity acting on a fluid, but a series of choices and actions to promote the continuation and development of a community of scholars and civic actors.

Acknowledgements. The list of ancestors we are grateful to is much too large to enumerate. Morgan must mention the late Bill Burch and Herb Bormann, two of his mentors from the Yale “School of Forestry.” Steward must mention the late Fakhri Bazzaz, his mentor then at the University of Illinois, and the late Tim Allen of the University of Wisconsin, one of ecology’s practical philosophers. We are both grateful to the Hixon Center at Yale University for bringing together an amazing community of friends, mentors, students, colleagues, and change makers to celebrate our two retirements this year. This entire group is a sterling example of ancestorhood.

about the writer

Samarth Das

Samarth Das is an Urban Designer and Architect based in Mumbai. Having practiced professionally in Ahmedabad, Mumbai, and subsequently in New York City, his work focuses on engaging actively in both public as well as private sectors—to design articulate shared spaces within cities that promote participation and interaction amongst people.

Samarth Das

Our efforts today carry with them the hope for a healthy future for the generations to come.

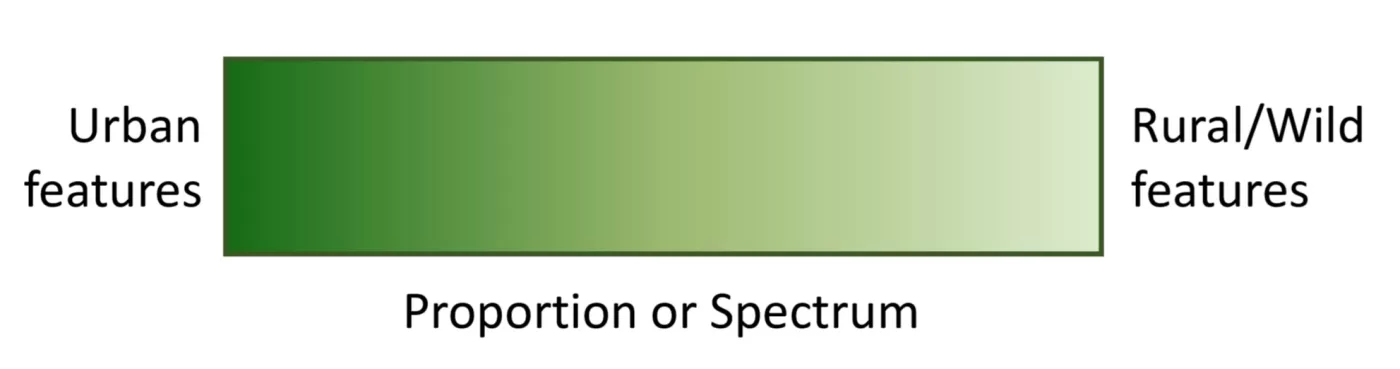

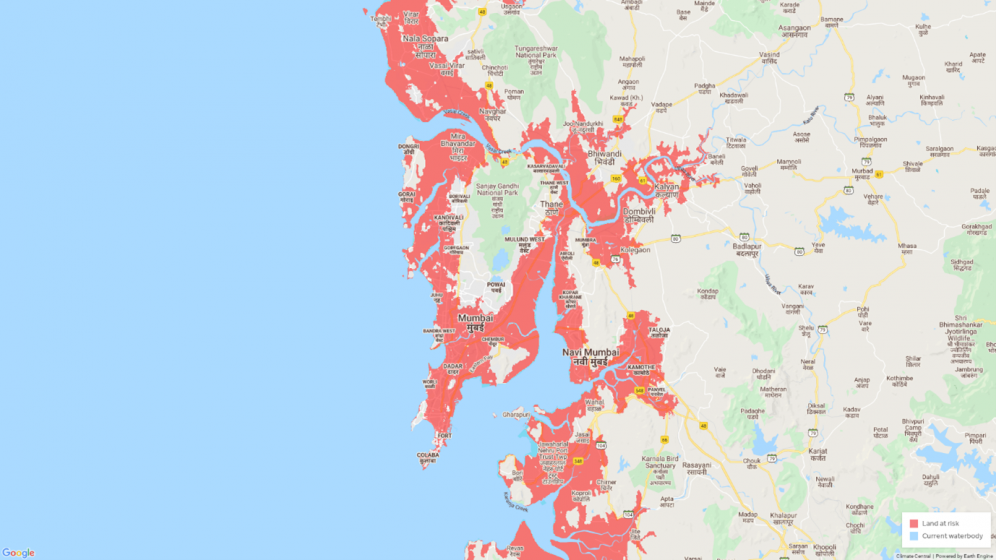

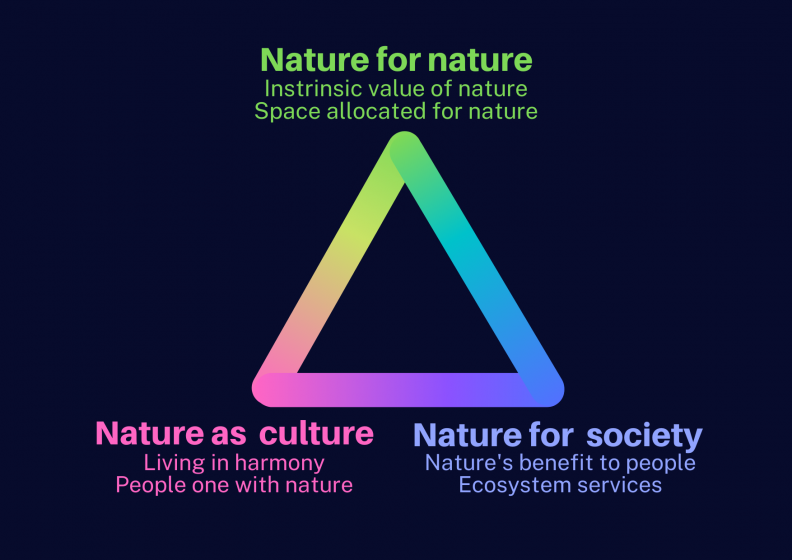

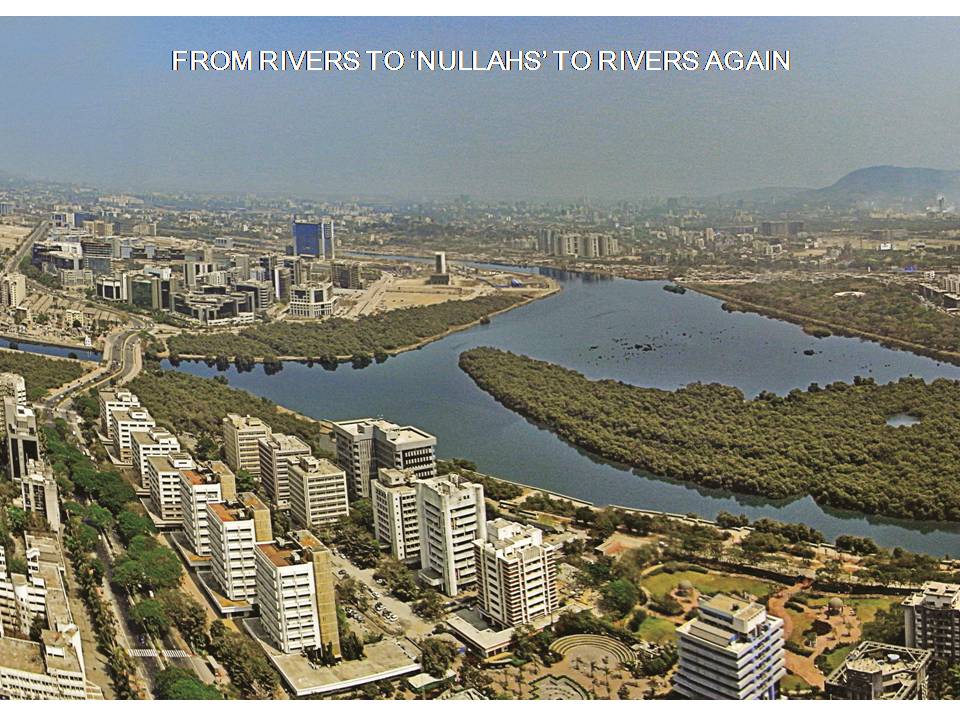

When we think of our ancestors, we reminisce and revel in the romance of a time when our environment was healthier, the air and oceans were cleaner, a time when nature truly flourished. For me, it is a sensorial deep dive into how people lived―how they occupied space, their livelihoods, their relationships with one another, their surroundings and with nature, and how they negotiated the early trends of urbanization and city life. Today, in the pursuit of rapid development, we have tipped over the scales and are as far away from thinking of nature as we have ever been. As an architect and urban designer, I am always looking for cues on how to restore some balance within our urban environments. People living in cities in our subcontinent are growing further away from nature, let alone interacting with it frequently for the relief and much-needed moments of pause it provides. As a people, we are losing empathy towards nature, being embroiled in our daily lives with utter disregard towards our already severed relationships with what is “natural”.

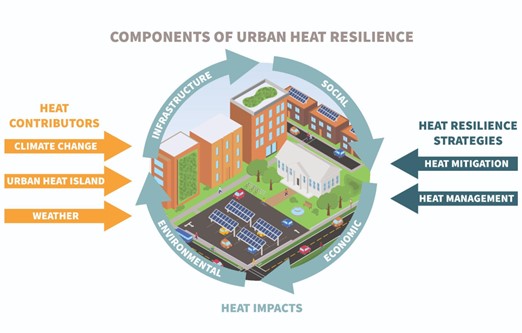

But not all is lost. While time is not on our side, time itself is the greatest healer. Nature finds a way of its own, and we must give it space and time to recover and reclaim lost ground. A transition to nature-centric approaches from the obsessive people-centric approaches of today is the need of the hour. Understanding this will help formulate ways of addressing the climate and environmental degradation at hand today.

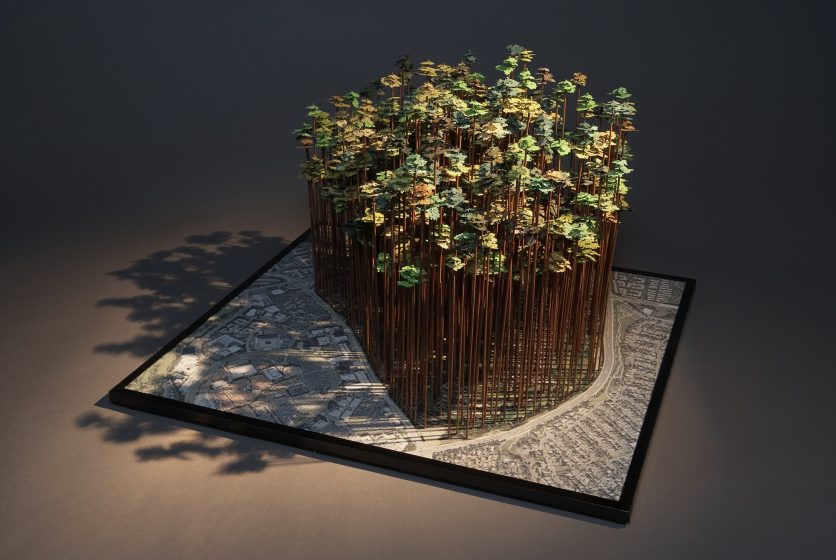

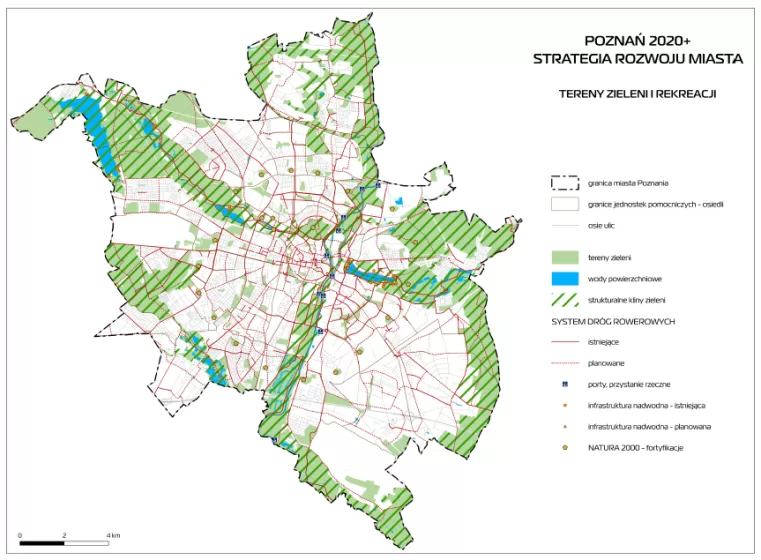

We must put ecology at the forefront of all our endeavors. Bringing natural areas back into our cityscapes must be a comprehensive approach adopted by city and state governments. Instead of seeking solace in forests and greenscapes outside of cities, we leave them be and instead try to bring forests back into our cities. We must find ways to give flora and fauna a physical stake within our built environments. In a world driven by capital and its geography flattening approaches, policy makers and city builders should instead aim to define birds, bees, butterflies, insects, lakes, rivers, mangroves, hills, and forests as their key clients. By giving nature the respect it deserves, we ensure the longevity of the very lands that we occupy and enjoy today. Our focus must be to help damaged environments in and around our cities heal by ensuring that green areas are given sufficient buffer areas to proliferate, while new developments allow for natural ecologies to flow through them instead of building barriers and severing relationships that the ground shares.

Ancestral timelines are rapidly shrinking―ironically, like the nature within our cities. What was earlier considered to be a multi-generational timeframe to perceive varying forms of livelihood, transport, methods of construction, amongst others, are now compressed into much shorter timeframes. In this time of accelerated change, interacting and spending time with nature is an in-exchangeable facet to nurture children into becoming climate-conscious and responsible guardians of tomorrow. Observing nature and its processes itself is a patience and empathy-building endeavor. Through learning at home as well as local community stewardship programs that address biophilia, we can help build a culture of respect towards one another as well as towards nature. These cultural practices can be carried forward as important tools of sustaining balance in our environments. Collaboration that enables cross-pollination of ideas across various sectors of technology and innovation across all age groups, with ecological refurbishment as the core development principle, can help garner relationships with multi-generational positive effects. After all, our efforts today carry with them the hope for a healthy future for the generations to come. With this, we hope that our descendants look back at this time, and appreciate our efforts in restoring ecologies that have been lost―not revel in the romance of what today offers, but rather be thankful for the changes we have effected to restore and recover from the damage we have inflicted upon our planet.

about the writer

Chantal van Ham

Chantal van Ham is a senior expert on biodiversity and nature-based solutions and provides advice on the development of nature positive strategies, investment and partnerships for action to make nature part of corporate and public decision making processes. She enjoys communicating the value of nature in her professional and personal life, and is inspired by cooperation with people from different professional and cultural backgrounds, which she considers an excellent starting point for sustainable change.

Chantal van Ham

Being a good ancestor: weaving the Web of Life

The question is not only about which parts of the fabric of life we are risking to lose, but whether future generations will reconnect and live in harmony with nature.

When I think about being a good ancestor, I remember my favourite childhood story of Millie and Tom, two field mice whose wedding secret traveled through the poppy flowers, the corn, the bellflowers, and the wind. The story taught me that in nature, nothing exists in isolation—every whisper, every action, ripples through the living fabric that connects us all.

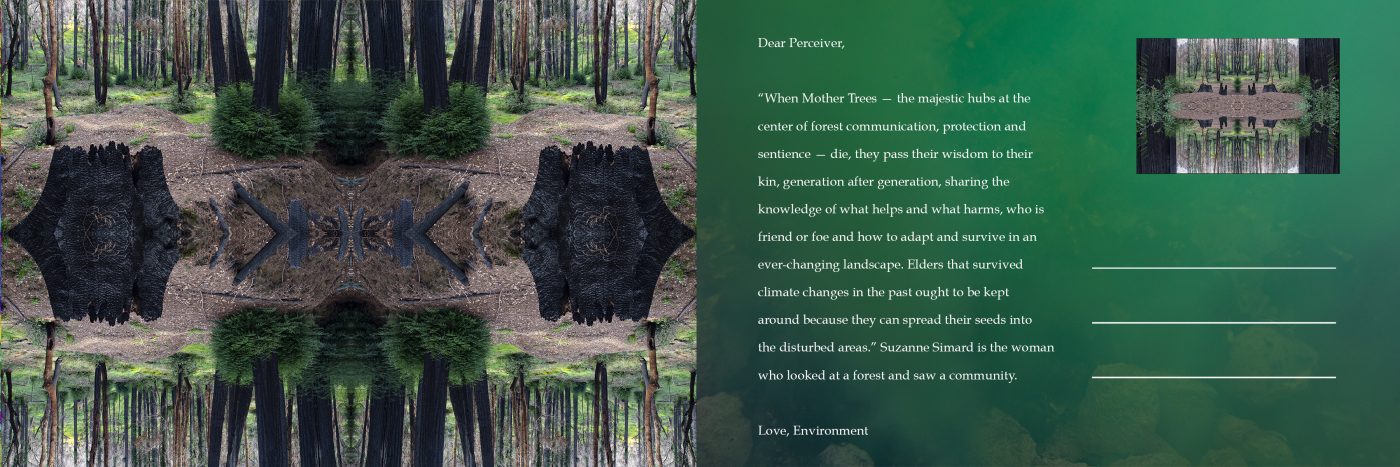

To be a good ancestor means recognising that we are not separate from but woven into this fabric, that rivers, forests, animals, plants, and humans share the same world, the same breath, the same future. We are threads in a tapestry that has been weaving itself for millions of years, and the mission of our century is clear: to protect and restore this intricate web of life before too many threads are disappearing.

What does care mean in this context? It means listening. Nature has tremendous wisdom. The underground fungal networks through which trees communicate and share nutrients, the bats that save billions in crop damage by controlling pests, or the wolves that changed entire river systems in Yellowstone simply by returning to their place in the ecosystem. Indigenous peoples have understood this wisdom for millennia, living as stewards in harmony with all other living beings. Learning from both indigenous and non-human wisdom, wherever we are, is at the heart of achieving our mission.

Being a good ancestor is about the daily practice of giving nature a space, in our lives, our work, our meetings, and our relationships. It is about opening windows to let birdsong in, about planting trees and flowers, by buying seasonally at our local farm, repair rather than replace, speak up at local planning meetings for green infrastructure over grey, and by sharing what you learn from nature. These small acts help restore the broken relationship between people and nature, thread by thread.

In cities, this is more challenging, but even more urgent, as we cannot wait for pristine wilderness to teach us about interconnection. We must create space for nature in the places where we live. For example, hospitals, schools, and elderly homes with healing and vegetable gardens, which means everything to health and wellbeing.

Being a good ancestor also means reaching beyond our community of the already converted. It means bringing those who are not yet part of this movement closer to nature—for their own nourishment, for their children, and for future generations. It means helping others discover what Indigenous wisdom has always known: that when we heal nature, we heal ourselves.

Alexander von Humboldt taught us in the 18th century that the world is a single interconnected organism: everything, to the smallest creature, has its role and together makes the whole, in which humankind is just one small part. Today, more than ever, we must live this truth and become stewards of the planet, honoring the millions of years of wisdom part of every ecosystem, every species, every relationship.

The question is not only about which parts of the fabric of life we are risking to lose, but whether future generations will reconnect and live in harmony with nature, so that they inherit a world where the poppy flowers still whisper secrets, where the rivers still run clear, where we know the names of plants and trees, and where the web of life remains intact enough to remain a home to them all.

about the writer

Diana Ruiz

Diana Ruiz is a researcher at the Nature-Based Solutions Center at the Humboldt Institute in Colombia. She is a biologist with a Master’s degree in conservation and use of biodiversity, and is currently developing her PhD in environmental science and technology. Her work focuses on researching and proposing management guidelines that improve the incorporation of biodiversity and its ecosystem services in urban-regional planning, promoting co-creation, implementation, and evaluation of nature-based solutions in these contexts.

Diana Ruiz

We should promote more conscious and active ways of giving space to spontaneity. This includes building new relationships with our environment — some of which might be “uncomfortable” — that allow us to deeply recognize that we have no control over what we assume to care for.

The way we relate to the world, as human beings, among ourselves and with other forms of life, results from different processes that we are not always aware of. The education we received, the opportunities we had to connect with nature during our lives, and the cultural context in which we grew up determine how we care for and take responsibility for the things that we value.

Much of this is also due to the ways in which we represent, understand and name nature. Being a good ancestor and caring for different forms of human and non-human life may begin with rethinking how we have constructed systems of knowledge and symbols of nature that, rather than recognizing and valuing its chaotic essence, have sought to organize, catalog, and control it.

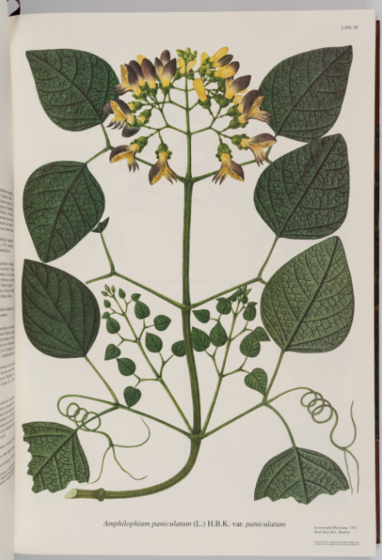

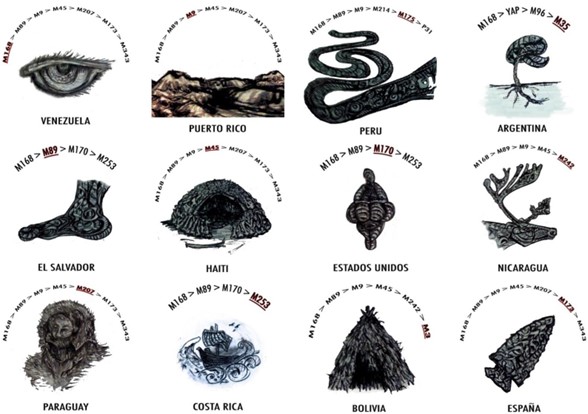

What are the consequences of basing our biodiversity conservation and nature care priorities on a Western knowledge system that is founded on a conception of living beings that abstracts them from their complex system? Indigenous peoples have represented nature in other ways, different from those we biologists have learned, which are the legacy of scientific expeditions that arrived in regions such as Latin America, driven by the Spanish crown. Although today it seems logical that knowing and naming a species requires representing, cataloging, and classifying it in isolation, other ways of generating knowledge remind us that through a comprehensive recognition of ecosystems and landscapes, we can also learn about, respect, and care for life, even better.

Abel Rodríguez Muinane, an artist and indigenous authority from the Nonuya people in the Amazon, is known as a “plant namer” due to his prodigious ability to remember the diversity of plant and animal species in his territory. Regarding his relationship with the jungle, mediated by memory, words, and images, he mentions in an interview published by the New York Museum of Modern Art magazine: “I hadn’t painted much, and at the beginning nothing came out right. It looked ugly. But what mattered was going to the forest in my thoughts and mind, and speaking and naming from there. Once I am there, I write down the colors and scents, where they are, what animals eat them, and when they rot. The translation is not easy—there are a lot of names I know in my language that I am not sure how to translate into Spanish. The paintings help me translate without words, to communicate what’s in my mind, and to show it in a way people understand. (…) The word is a technology that acts on the globe and determines how it operates, how it moves, and changes.”

The Western view, which currently dominates the strategies we use to conserve and restore natural systems, can limit our good intentions by prioritizing order and control over contemplation, respect, and a simpler understanding of complexity. Caring also means releasing control over what we want to care for and building a more honest and humility-based relationship from the essential: narrating, naming, feeling, and representing life in our day-to-day.

Valuing chaos and spontaneity so that biodiversity can thrive in our cities

How we design cities, as our habitat, including how we manage their nature, is a reflection of that symbolic relationship we have today with other forms of life, the narratives and aesthetics we prioritize. This is evident in how we value uniformity, cleanliness, and order over spontaneity and chaos.

Among the tools we have today to care for life and be good ancestors in our cities, we should promote more conscious and active ways of giving space to spontaneity. This includes building new relationships with our environment — some of which might be “uncomfortable” — that allow us to deeply recognize that we have no control over what we assume to care for.

about the writer

Paul Downton

Artist, writer, ‘ecocity pioneer’. A former architect with a PhD in environmental studies, Paul is distressed by how the powerful idea of ecological cities has been perverted, citing ’Neom’ as a prime example. Still inspired by his deceased life-partner Chérie Hoyle (1946-2024), Paul is continuing his graphic novel / epic poem / art project called ’The Quest for Wild Cities’ that he promised Chérie he’d finish along with his 80% complete ‘Fractal Handbook for Urban Evolutionaries’!

Paul Downton

Ancestry is baked in. It is part of cultural DNA. It is deep history―cultural memory―racial memory.

The concept of ancestors strongly implies that one is expected to respect one’s dead forebears. But to be a genuine ancestor, do you need to be dead? The Oxford Dictionary definition doesn’t seem to demand it:

“ancestor ― NOUN a person, typically one more remote than a grandparent, from whom one is descended” (my emphasis)

There is no active value judgement in that dictionary definition; “they were there and now they’re not”, but it seems to me that the concept of ancestors is about people who were alive in the past and left information, ideas, ceremonies, social patterns, tools and constructions, and legends that became integral points of referral to the life and times of people who came after. Ancestors left stories in words, music, and art forms developed over many lifetimes, and these stories from the past have contributed strongly to shaping the present―and hence the future. That’s a large part of what cultural transmission is all about.

What about the living ancestors? Are they vulnerable simply because they’re old or on the brink of passing from life? Are their stories worth listening to simply because of the storytellers’ experience of life? The answer to that is almost certainly “yes”, but what if your forbears turn out to be those ancestors of dubious renown who failed their remit and created havoc and damaged the world? We can typically see an abundance of cautionary tales when things “go wrong”, but there are any number of stories about children who try so hard not to do the things their parents did that they create new lessons. It may be harder to find clear indications of what has “gone right”, after all, humanity has long tried to capture the “good” ideas and turn them into “thou shalt” commands set in stone, and that hasn’t always turned out well either.

All living organisms or systems seek to maintain the conditions of their own existence; understanding what those conditions are is essential. That understanding may not be conscious. We may be the only species we know of that has the potential to consciously understand and maintain the essential conditions of its own existence at the global level. There may be pockets of knowledge about these “essentials”, but that doesn’t guarantee that the necessary knowledge for survival is sufficiently integrated in the wider culture to be significant, ie, is capable of both informing and changing the activities of that culture so that the preconditions for its survival are achieved. And lauded individuals of obvious cunning have made pronouncements that fly in the face of the logic in self-survival―“History is bunk”, said Henry Ford.

If you’re still alive and kicking and you do decide what kind of ancestor you want to be, you’ll never know if you succeeded.

Ancestry is baked in. It is part of cultural DNA. It is deep history―cultural memory―racial memory. It is fallible. Stories weave some of the oldest cultural patterns that people have ever made, but we cannot know for certain what any of them really mean―is the story of Noah, the Flood, and the Ark a flawed description of actual events, i.e., is it an attempt at a historical record? How much has it been embellished over the centuries by people who were never there? Is it just a story to market a new god by jumping on the back of an exceptional natural disaster?

You obviously can’t literally go back before their death and ask an ancestor anything; you have to divine it from the stories and rituals that have succeeded in surviving the distorting whispers of history.

I would explicitly exclude AI from any of this kind of patterning, even if we accept that language-based machine “learning” contains enough “truth” to be worth talking to.

We know that real individual and cultural memories are unreliable and subject to distortion over time. Humans have responded with myths and legends, which are typically non-literal versions of complex social memories that have found a way to survive. The best are understood as stories that can be interpreted for their moral guidance, even when people are inclined to argue about those interpretations. The Bible, anyone? The most resilient of the great faith traditions pick up on this process of interpretation as a structured, dialectic way of learning; The Torah, anyone?

I’m inclined to the view that the work of worthy ancestors is to help develop and sustain the culture which, in turn, sustains the essential conditions for maintaining that culture through deep time, defined as several generations or more.

It has been just over three years since I wrote the stanza that I decided to make the very last one in Canto 4 of the 329-verse epic poem component of a graphic novel I’ve been working on for a decade or more. I’ve called the novel “The Quest for Wild Cities”, and for me, this final stanza sums up what it’s all about, and it seems to fit this Roundtable quite well:

LXXXIV.

Your job is to be a good ancestor.

Your job is to remember the legends.

Your job is to know what we are here for

and to know the past on which it depends;

the past doesn’t die, your job never ends;

your body and soul are mixed with the world

making wild patterns as nature intends,

chaotic beauty in an endless whirl

scattered like brave fractals in a wave’s breaking curl.

about the writer

Martha Fajardo

Martha Cecilia Fajardo, CEO of Grupo Verde, and her partner and husband Noboru Kawashima, have planned, designed and implemented sound and innovative landscape architecture and city planning projects that enhance the relationship between people, the landscape, and the environment.

Martha Fajardo

Being A Good Ancestor: Landscape as a Vaccine and the Relational Cities We Must Imagine

What landscapes of life—ecological, emotional, and relational—will we choose to leave in the hands of those who come after us?

For me, that is the essence of being a good ancestor.

It is about choosing the legacy we leave—deciding whether we transmit the viruses of fear, fragmentation, and hatred that today spread with alarming ease, or whether we choose, instead, to act as vectors of what Gustavo Wilches-Chaux calls viruses of life: forces of hope, tenderness, and ecological reciprocity. These viruses of life have the capacity to restore our collective spirit and reconnect us with the living world.

Through this lens, today’s projects offered something remarkable. The designs prioritized the needs of non-human species—pollinators, birds, trees, fungi, and microorganisms—while embracing human well-being. They showed that urban design can become an instrument of healing, not only for people but for entire ecosystems.

This understanding was deepened through my experience as a juror for the Form Follows Life— Reinventing Cities competition. Participating in this visionary initiative was intellectually and emotionally transformative. I witnessed a new generation of designers, landscape architects, ecologists, architects, artists, scientists, and planners—young people from 38 countries—imagining cities not as machines of efficiency but as ecosystems of care. Their proposals were vibrant testaments to the idea that urban futures can nurture life in all its forms: human, vegetable, animal, microbial, visible, and invisible.

Landscape—whether a tree casting shade on a street, a biodiverse corridor threading through a neighbourhood, or a night sky unpolluted by artificial light—functions as a kind of emotional vaccine against the global pandemic of hatred amplified by digital noise. Nature restores what hostility erodes: the ability to listen, to imagine, to empathize.

Every act of cultivating, restoring, or defending a landscape becomes an act of intergenerational care—a deliberate recharging of what Wilches-Chaux calls the “battery of hope”.

Landscape design revealed that a profound paradigm shift is underway. At its heart lies the principle of life’s relationality: the understanding that all beings exist within a web of interdependence. The most compelling proposals demonstrated the radical potential of collaboration—between architects and biologists, engineers and artists, communities and ecologists. Breaking disciplinary silos is not only good practice; it is a form of ancestral care.

It invites us to imagine cities not as sites of extraction and exploitation but as places of care, connection, and regeneration. By prioritizing life’s relationality, it challenges us to create spaces that are not only sustainable but also life-affirming.

Central to this vision is the concept of living symbiosis—designing cities that foster deep mutual relationships between humans and the natural world. “Designing for life” means creating urban spaces that support and enhance the intricate web of interdependencies that sustain life, transforming them into landscapes of life where biodiversity and human well-being flourish in harmony.

As we look to the future, the insights from these experiences can serve as a guiding light. They remind us that the urban and the natural are not opposites but parts of a larger, living whole. By designing with this understanding, we can create cities that truly reflect and enhance the web of life.

Being a good ancestor means understanding this, honouring it, and acting accordingly. It means choosing to sow the viruses of life—care, connection, regeneration—so that future generations inherit landscapes capable of sustaining dignity, beauty, and meaning.

And perhaps the most important question remains:

What landscapes of life—ecological, emotional, and relational—will we choose to leave in the hands of those who come after us?

References & Links

- Gustavo Wilches-Chaux, “Una vacuna contra la pandemia de odios”: https://razonpublica.com/una-vacuna-la-pandemia-odios-invade-la-humanidad/

- Form Follows Life – Reinventing Cities (Non Architecture Publishing, 2025):

Bina, O., Silva, D., Fokdal, J., & de Stefano, L. (2025). Form Follows Life: Reinventing Cities. DOI: 10.57854/ulisboaics.9rc5-nx74.2025

https://lnkd.in/ezKGMHAx - Grupo Verde https://grupoverdeltda.com/

about the writer

Rosa Cerarols

Rosa Cerarols is a geographer and cultural activist. She is an Associate Professor in the Department of Humanities at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, where she teaches and conducts research in geohumanities, cultural geography, gender, and landscape studies. Beyond academia, she co-founded Konvent, a multidisciplinary space for cultural programming and artistic residencies, and has curated exhibitions and programs that connect art with territorial dynamics.

Rosa Cerarols

Connecting ecofeminism with the ethics of being a good ancestor reframes environmental responsibility as a practice of staying with the trouble.

Being a good ancestor requires asking ourselves if we want to be a seed or become a residue. This implies a call to action in grounding to Earth acting ultralocal but using planet thinking with clear ideas. For me, the notion of feminist counterapocalypsis offers a critical response to dominant narratives of collapse that frame climate and social crises as inevitable, totalizing ends. Rather than denying the severity of planetary breakdown, feminist counterapocalyptic thinking resists the political effects of apocalyptic imaginaries: paralysis, fatalism, technocratic salvationism, and the normalization of sacrifice. From this perspective, the multidimensional crisis is not an exceptional future event but an unevenly distributed condition already shaping the lives of many human and more-than-human communities. What is at stake, then, is not how to survive “the end,” but how to live responsibly within ongoing conditions of damage.

This reframing connects to me with the ethical imperative of *being a good ancestor*. A feminist counterapocalyptic lens (or simply ecofeminist), complicates this temporal and moral horizon by insisting that ancestry is not only about distant futures, but about the everyday reproduction of livable worlds in the present. To be a good ancestor is not merely to leave behind a stable planet, but to cultivate relations of care, responsibility, and restraint within damaged landscapes that will inevitably be inherited.

Feminist counterapocalypsis shifts attention from heroic acts of salvation to the mundane, relational labor that sustains life: caring, repairing, maintaining, and making space for others—human and non-human alike. In this sense, ancestry is understood not as lineage or legacy, but as relational continuity. Our actions become ancestral not because they guarantee progress or redemption, but because they shape the conditions under which future beings will be able to inhabit, adapt, and respond. This perspective rejects the fantasy of control embedded in apocalyptic and techno-futurist imaginaries, replacing it with an ethics of situated responsibility and humility.

Many communities have long been forced to act as ancestors under conditions of dispossession, colonial extraction, and environmental violence. For them, the future has never been secure, and care has always been practiced amid uncertainty. Recognizing this challenges universalizing narratives of crisis and highlights existing practices of endurance, mutual aid, and commoning as already-ancestral forms of action. Being a good ancestor involves learning from these situated knowledge rather than imposing abstract solutions.

From my point of view, connecting ecofeminism with the ethics of being a good ancestor reframes environmental responsibility as a practice of staying with the trouble: acting without guarantees, acknowledging interdependence, and accepting that the worlds we pass on will be shaped as much by repair and care as by loss. It is an invitation to abandon the search for final solutions and instead commit to ongoing, collective work of sustaining conditions for life—imperfect, vulnerable, and shared—across generations. I want to be a resilient seed.

about the writer

Bettina Wilk

Bettina Wilk is a sustainable urban development practitioner with expertise in nature-based solutions, urban resilience, and environmental governance. Bettina has worked with local authorities on policy integration, nature-inclusive urban planning and governance (Urban Nature Plans, EU Nature Restoration Law) with ICLEI Europe. She now leads projects and services development on urban nature at The Nature of Cities Europe, fostering strategic partnerships to advance sustainable urban futures.

Bettina Wilk

Being a good ancestor means shaping cities and policies that recognize multispecies interdependence and grant the more-than-human world a legitimate voice in how space, resources, and futures are negotiated.

In times of rising political turmoil, growing polarization, and interconnected crises, the question of what good ancestorship looks like has taken on new urgency. As the future becomes harder to predict, communities, ecosystems, and institutions are expected to adapt quickly, often without the clarity they need to act. Against this backdrop, the concept of being a good ancestor feels immediate and pertinent. From a socio-ecological perspective and one of strengthening human-nature-connections, it asks how we can rethink proximity, governance, and stewardship so that institutions, communities, and ecosystems are better equipped to care, adapt, and endure in the decades ahead.

For a long time, my ambitions led me to believe that impact must be inextricably linked to scale: European and global reach, agendas, and policy targets. It is a paradox familiar to many in the field of sustainability: the larger our aspirations, the further they drift from the places where we can act with immediacy, humility, and depth.

Yet, ancestor-oriented thinking is profoundly local. It requires us to re-anchor ourselves in proximity, to attend to the local community, to our natural surroundings, and to immediate needs. It reorients us toward the responsibilities that come with presence: noticing when a tree suffers, when a riverbank erodes, or when a neighbor feels unheard. And it allows us to act where our hands and voices actually reach.

The future of each place, no matter how small or large, is shaped by countless local decisions: who shows up to a community meeting, who takes the time to repair something that is breaking, who brings people together around a community garden that is now cared for collectively. These micro-acts of care often echo the longest. They accumulate quietly into futures that feel held, not abandoned.

Our governance and planning systems are in urgent need of repair and reform if they are to enable collective care and stewardship for nature beyond individual actions, particularly in contexts where people, priorities, and conditions are constantly changing. Collaborative and stewardship-focused governance, grounded in participatory engagement mechanisms and multi-stakeholder management arrangements, should take the place of one-off consultations, rigid administrative structures, and inflexible procedures. Nature and ecosystem guardians, such as indigenous communities living in harmony with nature, as well as land and forest managers, should be rewarded.

Crucially, these governance instruments must be designed to listen, not as an afterthought but as a core function. Embedding values-based and narrative approaches into planning and decision-making helps ensure that people recognize themselves, their concerns, and their lived realities in the structures that shape their environments. Where governance makes space for diverse values and perspectives over time, it can counter feelings of exclusion and disconnection that too often fuel polarization and misinformation.

Legacy is about building inheritance-ready structures that are fit for use in 20, 50, or 100 years’ time, resilient enough to buffer and absorb emerging shocks and shifts, and adaptable.

Finally, being a good ancestor also means reconsidering who, and what, we treat as part of our collective inheritance. The more-than-human world is not a backdrop to human societies but an integral part of them. Rivers, wetlands, pollinators, soil organisms, and urban trees are not external to our future; their trajectories are inextricably linked to our own.

This perspective calls for an expansion of our moral and political imagination. When non-human lives are understood as co-inhabitants rather than external objects of management, governance, and planning cannot remain unchanged. Being a good ancestor, in this sense, means shaping cities and policies that recognize multispecies interdependence and grant the more-than-human world a legitimate voice in how space, resources, and futures are negotiated.

about the writer

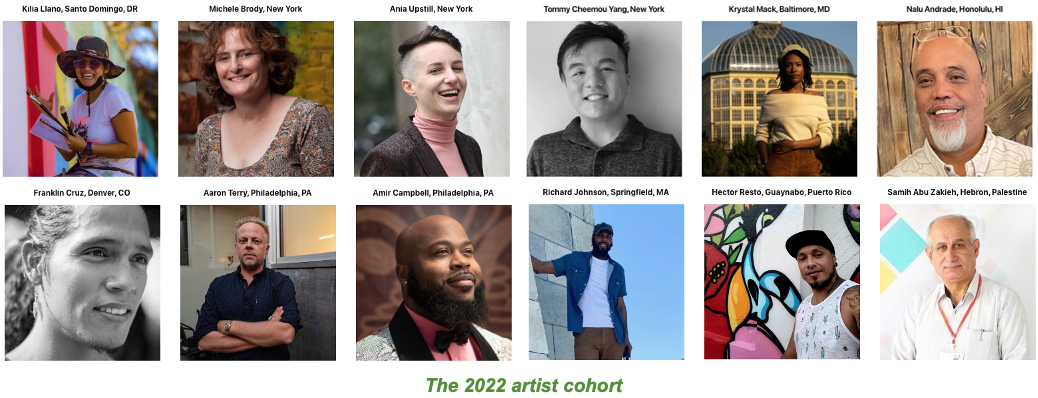

Ania Upstill

Ania Upstill (they/them) is a queer and non-binary performer, director, theatre maker, teaching artist and clown. A graduate of the Dell’Arte International School of Physical Theatre (Professional Training Program), Ania’s recent work celebrates LGBTQIA+ artists with a focus on gender diversity.

Ania Upstill

We get to create a world that values ancestry in both directions, and which brings everyone into the conversation.

When I think about being a good ancestor, I normally think about the future, especially future generations. After all, those are the people that I will be an ancestor to, and I hope to be a good one. I am also an arts educator, so I am often in contact with young people. If you had asked me three months ago what made a good ancestor, I would have followed that train of thought and emphasized the importance of educating the youth and passing down knowledge, ensuring that they are ready for the world and prepared to be kinder, better, maybe even our salvation. This fall, however, I had the opportunity to work with a group of elder queer people in an intergenerational project. These wonderful humans are my own ancestors, and in our interactions, I realized how important it is to look backwards as well as forwards, to listen to and learn from those older than us.

We came together to work on a piece for the Transgender Day of Remembrance, and during our ten sessions, we told stories, shared experiences, and created theater together. As we worked, I was reminded of how little I interact with people in the generations above me. Outside of my parents and godparents, I have only one friend who isn’t my age or younger. Yet I was deeply moved by spending time with these elders, and cognizant of how much I learned. They modeled how to slow down, how to take your time thinking and moving. They appreciated the time we had together just for its own sake, as a gift of connection, without it having to have a product. We spent a lot of time just talking, rather than focusing on what we were “supposed” to be making, and our time together felt radical because it wasn’t focused on productivity. In fact, it modeled a different way of being, one that I think we will all need to shift towards to change our late capitalism, consumer-oriented worldview, and hopefully, our planet.

My narrative has shifted. Yes, we need to educate our youth and think about caring for the planet that they will inherit. And that’s not all. To be good ancestors, we also need to connect with those older than us and look to history as much as we look to the future. Older people have lessons to share. Many of them are forced to live slower lives, to not take their health for granted, to value human connections in new ways as they get older. Our culture puts a huge emphasis on youth and has a real disdain for the elderly. Instead of falling into that trap, we can value our elders and bring them into the conversation. We can learn from and with them and treat our ancestors with care while we become ancestors ourselves. We don’t need to reinvent the wheel, and even as we don’t have to recreate the world according to how it was when they were young. We get to create a world that values ancestry in both directions and that brings everyone into the conversation. After all, the world belongs to us, old and young. Let’s create a better one together.

about the writer

Lindsay Campbell

Lindsay K. Campbell is a research social scientist with the USDA Forest Service. Her current research explores the dynamics of urban politics, stewardship, and sustainability policymaking.

Lindsay Campbell

Since I can’t control my future legacy, I’m not sure that I can be remembered as a good ancestor―I have to be at peace with just being an ancestor and hope that’s enough?

I struggle with what it means to be a good ancestor when I’m just figuring out how to be a good mother to the person I love most on Earth.

I provide my daughter with the essentials: love, support, attention, care, nurturing, guidance, resources. But how much, in what ways, with what words, when to lead, when to step back, from what moral framework or cultural reference? It feels, honestly, improvisational. How often have we heard parents say they are “making it up as they go along?” despite so many centuries of thought and advice on how to be a good parent. At the core, I come back to love; if I anchor in love, I hope I’m getting the most important part right, and hopefully the rest can be forgiven.

But compared to my interaction with my parents or my daughter, I don’t have much, if any, contact with my ancestors. I know some of their names that we wrote on a family tree for our daughter. I see their faces in photographs that my husband and I put on our ofrenda for Dia de Los Muertos, a tradition I now share from his Mexican ancestors. Those faces include our genetic family but also our chosen family―those whose ideas and work and friendship have inspired us to claim them as our own. Because we are more than our DNA―we live in a rich, connected social world that inspires and shapes us. The faces also include our pets, those fuzzy family members that often teach us first about dying, mourning, and remembrance because of their shorter lifespans. And they include things without faces―an acorn from the oak that was cut down in our neighborhood park―that we want to honor as relations.

If I am lucky, I have stories, or fragments of stories, about my ancestors. “Lindsay looks like Daisy Mae”―my great-grandmother, whom I met when I was 3 and never knew, but when I saw a picture of her in her 20s, it was like looking into my own eyes. My great-grandmother on my mom’s dad’s side was a farmer in the Midwest who made excellent biscuits―I should try to get the recipe someday, or better yet to make them with my mom. A lot of my people were farmers―in Scotland, Ireland, and Germany. My grandfather’s family name Zenthoefer, translates to “tenth taker” aka “tithe taker” aka the “tax man”. These fragments are the stories I have. But beyond that, it’s hard to know how to look to them for guidance or grounding on what kind of an ancestor I should be.

So how do we know if ancestors are “good?” Some folks have deep ties to ancestral wisdom that they live and practice every day. Some folks have little written record of who their ancestors were – those histories have been obscured or erased. Some folks get into genealogy and unearth dark truths in their family histories―criminals, enslavers―that they then have to reckon with and work through. I haven’t done that probing, though I know my grandfather did some family research, and my mom recorded as oral histories, and I actually helped my mom transcribe with my fast typing in 8th grade. I should go back to it. I have no memory of the stories. That impulse to know more, to connect, to fill in the gaps of the missing stories comes from a place of asking―who am I? Where did I come from? Are we good? In truth, aren’t all of our lineages filled with good and bad people, saints and sinners, and aren’t we all a mix of both?

Since I can’t control my future legacy, I’m not sure that I can be remembered as a good ancestor―I have to be at peace with just being an ancestor and hope that’s enough?

I try my best to live my values and principles, to influence those in the small circle around me who influence others in ever widening circles and webs around them―because that is all I have. How do I express that? Through my parenting―improvisational though it may be―trying to raise my daughter to be a good human and learning so much from her reciprocally in the process. Through my family and friendships, though, I feel like our digitized world has made me more shallowly connected than I would like to be. Through my research, writing, and mentorship. I have no illusions of becoming a famous author, but I trust in the web of influence when I see the amazing young scholars and practitioners following after me, who might have taken a piece of wisdom or inspiration from my work, just as I have taken wisdom and inspiration from others. Through my care of the Earth―getting my hands into even a patch as tiny as an urban street tree bed affirms, for me, the interconnection of all beings. It is unseen, it is bigger than me, and it is awesome.

about the writer

Xavier Cortada

Xavier Cortada, Miami’s pioneer eco-artist, uses art’s elasticity to work across disciplines to engage communities in problem-solving. Particularly environmentally focused, his work aims to generate awareness and action around climate change, sea level rise, and biodiversity loss. Over the past three decades, the Cuban-American artist has created more than 150 public artworks, installations, collaborative murals, and socially engaged projects.

Xavier Cortada

The Art of Good Ancestry: Moving Humanity Forward

Being a good ancestor is not caring only for the people who share our bloodline. It is about caring for the people who share our time, our place, our challenges, and our hopes.

The best gift an ancestor can provide is to serve as a bridge. That is what we are, bridges carrying humanity across time. Biologically, we are part of an evolutionary process, a chain of nucleotides moving from one generation to the next. But the real movement, the movement that shapes lives long after ours, comes from something beyond the evolutionary chronicles of those four DNA molecules. It comes from the ideas we generate and advance through the lives we live, becoming the conduits through which meaning travels.

Ideas are the structure that lets us leapfrog the slow and random evolutionary process that mutations give us. They allow us to take our moment, make sense of it, refine it through experience, and offer it forward in a form others can use. Not only now, but in a way that transforms them so they, in turn, can give presence to those who follow. That, to me, is the work of ancestry: teaching future generations how to be more human and strengthening their capacity to extend that humanity.

A good ancestor gathers what they have learned and prepares it to survive uncertainty, whether it is an early death, a misunderstanding, a conflict, or a collapse. They act knowing that what we pass on is not just knowledge but a way of living that helps others carry meaning across time.

Throughout human history, we have relied on the same mechanism to do this: culture. Culture is how we embed meaning in forms that endure. Our deep ancestors understood this intuitively.

Sixty thousand years ago, as they moved across the African continent and beyond, they hunted, gathered, settled, and adapted. Yet, everywhere they went, they made meaning together. They formed language, ritual, and custom. They carved, painted, and sang. They took what the land offered them, whether it was pattern, danger, beauty, or sustenance, and transformed it into something they could share and something they could teach. Through art, they became a community, and in that shared act of making meaning, they became more interconnected, more interdependent, and more human.

Sometimes we forget that culture is not a product but a process, and its true resource is not the idea itself but the people willing to carry it. Art becomes real only when it is shared, when it passes from one life into another and inhabits them both, reshaping each in accumulating, unexpected ways. That exchange generates the momentum that keeps meaning alive — the quiet but insistent impulse to continue moving it forward so others can build on it. When someone steps into that work, feeling both the responsibility and the privilege of advancing it, that is ancestry in action. The ancestor’s life bends toward a future they will never see, and the recipient is shaped not only by the idea they inherit but by the generosity and intention carried within it.

We are not just creators of new ideas but curators of previous ones. Each of us takes in what earlier lives struggled to understand, makes sense of it in our own time, and sends it onward to people we will never meet. If we do not move those insights from past to future, they disappear. The line breaks. What survives is whatever we choose to receive, refine, and pass along. That is what makes us more than descendants. It makes us the living conduit through which meaning continues its journey.

Being a good ancestor is not caring only for the people who share our bloodline. It is about caring for the people who share our time, our place, our challenges, and our hopes. It also reaches the more-than-human world that will inherit our decisions: the coastlines, the wetlands, and the species navigating a century shaped by climate. What we pass on includes both the ideas we believe are worth carrying and the world required to carry them.